In February 1940, explorer Aurel Stein commenced what would become one of the most illustrious expeditions of his career. The Hungarian–British archaeologist undertook the task of recording, documenting, and investigating mounds—locally known as ‘theris’. Over three stages, he covered the distance from Haryana to Sindh and reported 97 archaeological sites on both sides of the dried Ghaggar River in the upper Ghaggar region. He explored from Hanumangarh in Rajasthan all the way to Bahawalpur, now part of Pakistan’s Punjab province.

Although the majority of expedition’s data remained unpublished, Stein’s final sojourn paved the way for future research that helped archaeologists identify sites and establish not only a timeline but a complete cultural sequence of the region. Based on Stein’s work, following Partition, archaeologist Amalananda Ghosh and his team undertook the first exploration along the dried bed of Ghaggar River—advancing research by identifying Harappan sites and even Early Harappan sites such as Sothi.

This demonstrates the enduring truth that research is an ongoing process and that, with every step, we move closer to the truth. Therefore, despite many lacunae in Stein’s study, it is important to revisit the last survey of the Ghaggar conducted before 1947.

Early years

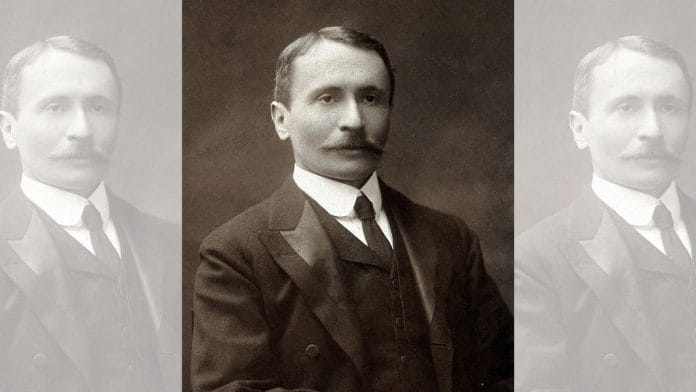

Born on 26 November 1862 into a Jewish family in Budapest, Stein was always interested in studying Sanskrit, Persian, comparative linguists, and classical philology. After receiving his doctoral degree in 1883, he conducted research in ancient Persian literature and archaeology at Oxford and Cambridge. He was always fascinated by the campaigns of Alexander the Great, which inspired him to experiment with research. When he arrived in India in 1887 and joined Panjab University as registrar, he finally had the opportunity to spread his wings and explore the art of discovery.

In between his administrative duties in Lahore, he got acquainted with Gandhara art and museum management and slowly started appreciating not just the Western influence in the art but also the presence of indigenous style. After conducting field work, he concluded that a research position would please him more than any administrative role. The knowledge he gained during the many field trips and by studying ancient artefacts helped him in befriending Lord Curzon during his trip to Lahore in 1899.

Curzon, who by then was desperate to bring changes in the state of archaeology in India, was impressed by a young Stein and encouraged his “roving expeditions on the borderlands as well as … Khotan project” (Mirsky 1977:89). This was the beginning of Stein’s expedition to Central Asia; he covered the entire Silk Route and gained the reputation of being the best surveyor of his time. During his expedition, Stein ventured into the Taklamakan Desert, located in what is now the Xinjiang region of China. This vast, arid stretch had remained largely unexplored by Western scholars at the time. His goal was to follow the ancient Silk Road and uncover the remnants of the once-flourishing civilisations that had inhabited the area.

Among Stein’s most significant finds on this journey were the Dunhuang Caves—also known as Mogao Caves—which is a network of Buddhist cave temples that contained thousands of ancient manuscripts, paintings, and sculptures. These caves, hidden in the Gobi desert for centuries, revealed a rich collection of early Buddhist texts, many written in languages like Sanskrit and Tibetan. The manuscripts provided valuable insight into the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road and its cultural impact across Central Asia.

By 1903, Stein not only conducted multiple expeditions but had also moved up the ranks from a university registrar to Inspector-General of Education and Archaeological Surveyor for the North-West Frontier Province and Baluchistan. He had wished to secure a position in India which would leave him with more freedom for scholarly work than his administrative university job in Lahore. He said that he “would be delighted to stay in a country of my scholarly interest”, and by 1903 got the position and freedom he embraced till the end.

Although the survey of Central Asia is among Stein’s most renowned and celebrated works, he had also successfully surveyed a wide landscape from Jammu and Kashmir to West Bengal. With each project, he added another feather in his cap and left behind a celebrated legacy. During his stay, he utilised his field experience to explore the unknown aspects of ancient India. His work in Kashmir from 1888 to 1896 is one his best and most understated.

Rajatarangini, a Sanskrit text which well preserves the history of Kashmir, has drawn attention of many orientalists like HH Wilson and Georg Buhler, who made several attempts to find the genuine manuscript. But it was Stein who was able to locate the complete original text and prepare its critical edition in 1892 and a complete English translation (Stein 1900a). During this time he also prepared a complete catalogue of Sanskrit manuscripts in the Raghunathan Library.

Apart from this, Stein explored the Salt Ranges, Swat and Buner, South Bihar and Hazaribagh, Balochistan, and the Indus basin where he investigated the famous site of Nal after then Director General of Archaeological Survey of India John Marshall’s insistence.

Also read: Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age report is a turning point in Indian archaeology. It needs more research

The last sojourn

During two winter seasons between 1940-43, Aurel Stein led his last expedition along the dry bed of Ghaggar-Hakra with the goal of finding the traces of river Saraswati, which finds mention in Rig Veda. But little did Stein know that he actually did more than that for the archaeological research in India. He surveyed from present day Hanumangarh to Bahawalpur and located nearly 100 sites belonging to prehistoric as well as historical period, while also conducting trail trenches at some sites. Although he was unsuccessful in defining the exact chrono-cultural history of the region, he did make some very interesting observations regarding the spatial distribution of the sites that helped future scholars like Ghosh and Katy Dalal during their field surveys. He extensively spoke of sites like Munda, Bhadrakali Mandir, and Derwar.

Unfortunately, Stein passed away before he could publish his last survey details. But his legacy continues to shape archaeological methodologies and our knowledge of ancient trade routes, religious movements, and cross-cultural interactions.

Also read: See how Gujarat’s Kanmer links to Dholavira, Harappa—India’s urbanisation journey lies here

Legacy lives on

In the end, Aurel Stein’s contributions to archaeology were nothing short of transformative. His journeys, from the remote deserts of Central Asia to the riverbeds of India, helped unlock the secrets of ancient civilisations and set the stage for future discoveries. While his final survey of the Ghaggar-Hakra region remained largely unpublished during his lifetime, it became a crucial stepping stone for subsequent research, guiding archaeologists in uncovering and understanding the rich history of the Saraswati river and its ancient sites. Stein’s passion for exploration, his sharp observations, and his tireless pursuit of knowledge created a legacy that still echoes in the work of scholars today. His findings not only shaped the course of archaeology but also bridged cultural divides, sparking a deeper connection between the East and the West.

Even with the gaps in his work, Stein’s influence continues to inspire and motivate archaeologists and researchers, ensuring that his spirit of discovery lives on for generations to come.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. Views are personal. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha.