Much before Kashmir was known just for conflicts, its spiritual traditions like Tantra were shaping modern art across the world. It touched everyone from the masters like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Mark Rothko to those interested in spirituality in the Western world.

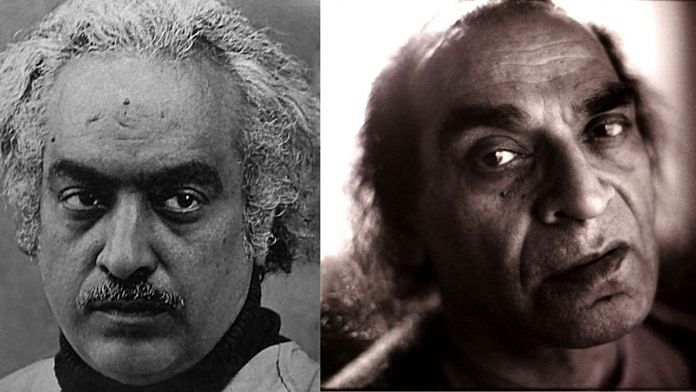

And at the centre of the art that came from these syncretic religious traditions were Ghulam Rasool Santosh and Sohan Qadri.

G.R. Santosh

When Kashmiri artist Ghulam Rasool Santosh hiked up to Amarnath in 1964, the giant Himalayan cave at 17,000 feet, and beheld the ice formation that pilgrims consider a manifestation of Shiva, he was jolted into a deep trance.

“I was overwhelmed by a joy that I cannot describe in words. I wished I had wings so that I could soar like a bird all around and absorb all this purity in me, to wash away all the stains of my inner self. I felt that the Supreme Lord, in the form of Shiva, was divulging his ever-benevolent presence there. After I returned from the Amarnath Yatra, a distinct change came in me.”

Scores of people have reported similar experiences during their first visit to the holy site. The ancient pilgrimage to Amarnath, which has drawn hordes of devotees since time immemorial, has been cancelled only a few times — because of terrorist threats, or more recently, in 2021, due to the Covid pandemic.

After his transformative experience at Amarnath, Santosh devoted the rest of his life to the study of Tantric Shaivism, one of the major spiritual traditions of Kashmir, and went on to produce a vast body of work that reflected his inner journey.

Born in 1929 to a family of modest means in Chinkral mohalla of Habba Kadal, Srinagar, Ghulam Rasool Dar grew up in the company of local artisans, learning the arts of papier mache and silk weaving from them.

After his father’s death, he dropped out of college, and earned a living by whitewashing walls, painting signboards, and working with woodcarvers and shawl weavers. In his spare time, he painted expressionist landscapes that eventually caught the eye of Syed Haider Raza, a doyen of Indian modern art. He recommended Santosh to the renowned painter N.S. Bendre, who at the time was the head of fine art at MS University in Baroda. He was accepted as an understudy, and, in 1954, he set off to Baroda to start a new chapter. Around the same time, he married his childhood sweetheart Santosh, a Kashmiri Pandit girl, an act that went against the norms. He took her name and started calling himself G.R. Santosh.

On returning to Kashmir a few years later, he produced a series of Paul Cezanne-inspired landscapes and Cubist works that were masterly in their own way. But Santosh found his true calling only after the transformative experience at Amarnath in 1964.

The influence of traditional Buddhist Thangka paintings and Tantric sacred geometry can be seen clearly in all his subsequent works. The one motif that appears frequently is a stylised version of the Sri Yantra. The Sri Yantra is a visual meditation aid consisting of nine interlocking triangles – five pointing downwards – symbolising Prakriti, the feminine essence of the universe — and four pointing upwards – signifying Purusha, the masculine principle. The Sri Yantra represents their unity at the most fundamental level.

The recurring image of what appears to be a figure seated in Padmasana, the lotus pose, also appears in many of his works.

“Viewed from a certain perspective, most of Santosh’s Neo-Tantric paintings look like stylised portraits of the female form, seated in Padmasana” wrote Shantiveer Kaul in The Art of GR Santosh. “This is no mere coincidence. There is a definite suggestion of the female torso in the placement of geometric elements within the composition. This stylisation is symptomatic of the devotion of Santosh for Shakti, the Divine Mother.”

Indeed, the Tantric traditions are female-centric, heavily practice-oriented, and as such, distinct from the more conventional modes of worship. Many of its signature rituals, designed to jolt human consciousness out of its habitual patterns, were considered too radical for the polite society of the time.

The focal point of all Tantric art is the Bindu. In Yogic terminology, the Bindu is the seed of all creation. It is the source from where Shakti emanates to manifest the world and the place to where she ultimately returns. In Tantric sects within Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, the universe is depicted as a mandala with a Bindu in its centre. Mandalas represent the relationship between the micro and macrocosm and are designed for use as a meditation aid. The importance of the Bindu is apparent in the work of Santosh and his fellow travelers on the Tantric path, including Biren De, Sohan Qadri, S.H. Raza and P.T. Reddy.

Also read: How Kashmiri Islam, tolerant and love-based religion, changed to hardened Sharia version

Sohan Qadri

Sohan Singh, a contemporary of Santosh, was also deeply influenced by India’s syncretic religious traditions. He changed his name to Sohan Qadri as a tribute to his Sufi teacher Ahmed Ali Shah Qadri. Born into a prominent farming family near Kapurthala, Punjab in 1932, Qadri grew up in the company of two powerful mystics, Bikham Giri, a Bengali Tantric-vajrayana yogi, and Ahmed Ali Shah Qadri, a sufi. Both teachers had a major influence on young Qadri and showed him how higher states of consciousness could be accessed through art, meditation, dance and music.

Qadri became a Yogic adept in his own right whose paintings were central to his spiritual practice. “When I start, I am completely blank. When I’m friends with blankness, good things come. I have no idea what will come, I must be clean like the canvas-innocent, spotless” he said in an interview in 2005. “I have 20,000 ideas, but they must be thrown away. I must be as empty as the canvas, without concepts, evoking images that my hand will fix.”

Qadri’s philosophy of art could be encapsulated in the first line of the Yoga Sutras, a pre-eminent Yoga text authored by the sage Patanjali: Yogah Chitta Vritti Nirodaha. Loosely translated, it means Yoga is the cessation of fluctuations of mind.

As Qadri put it, “Some paintings have the power to break down your sensational expectation because they don’t offer you anything to stand on, they have the power to break down your chattering mind, then you fall into silence. That’s what my paintings try to do, because in silence we are the same. The moment we talk, we start differing.”

Like Santosh, Sohan Qadri’s body of work was exhibited at prominent venues around the world and still continues to be displayed at major showings of Indian modern art.

Also read: Atheism, abortion, art, sex — things Mira Nair film on Amrita Sher-Gil can’t miss

Kashmir, Tantra and the world

Tantric art also found a receptive audience in the West that was itself going through a counterculture renaissance in the ’60s and ’70s. Mystical traditions from South Asia such as Yoga, Taoism, Zen Buddhism, Tantra, and Bhakti-infused Hinduism were exploding in popularity across North America. The arrival of the Beatles in Rishikesh in 1968 to study transcendental meditation with Mahesh Yogi for a year was the catalyst that lifted Indian spirituality from the fringe into a full-blown cultural phenomenon that continues to influence American religious life even today.

Iconic American painters such as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Mark Rothko, who came to prominence during the screaming sixties and swinging seventies, have all noted the influence of Tantric aesthetics on their art. Johns, for instance, identified the source of the imagery in one of his well-known abstract works as a 17th-century painting from Nepal that depicts the sexual union of the Buddhist deity Samvara with his divine consort Vajrayogini.

“For both neo-tantric artists and Western modernists, the tension between the spiritual and the material found expression through symbols that defied particular iconographic or culturally-grounded systems and instead evoked broader universal expressions of spirituality, patterns in the universe, and sense perception” wrote art scholar Rebecca Brown in her essay on the neo-tantric movement. “Articulating the relationship between spiritualism and materialism forms one major part of the modernist struggle; this relationship is in many ways resolved by tantric thought, one reason that it held such appeal for both Western and Indian culture of the 1960s and 1970s.”

Indeed, for Tantra practitioners, everything in the world is a manifestation of Shakti, or the supreme consciousness that binds all creation, and as such nothing in it can be shunned or rejected. Seen as a vehicle of Shakti, the body, its sense organs and especially the breath, are used in specific practices designed to boost the spiritual power of the aspirant. These include powerful sexual rites in which the sex drive itself is transmuted into spiritual energy. The male and female organs of procreation are represented as the Linga and Yoni, forming an integral part of Tantric ritual praxis.

The valley of Kashmir, with its deep spiritual ethos and myriad cultural influences, was the perfect environment to nourish Santosh and his sublime meditations on nature, the cosmos and the Self. In Tantra, he found a practice that brought about transformation by peeling off the layers of personal history and identity, because not only were they seen as irrelevant, but as impediments in the mastery of the Self. Qadri, with his early initiation into the esoteric arts, found himself on an equally rigorous path towards Self-realisation.

As Kashmir and the wider south Asian region finds itself in the throes of prolonged sectarian conflict, perhaps it is time to revive the radical art of Tantra whose practice demolishes the very identity constructs that led to these conflicts in the first place.

Vikram Zutshi @vikramzutshi is a journalist, filmmaker and cultural critic. He runs The Big Turtle Podcast and edits Sutra Journal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)