The Indian Constitution, as American historian Granville Austin remarked, is an elite document. Despite its enactment and endurance for 75 years, the Constitution did not become a people’s book. But that is changing now. Communities and protesters are slowly owning and celebrating it.

“Gita se na chalta hai na chalta Quran se, chalta hai desh hamara Bhim ke Samvidhan se (our country is neither governed by the Gita nor the Quran, it is governed by Bhimrao Ambedkar’s Constitution).” With this catchy song, the Bheel community in Udaipur, Rajasthan is not only engaging with the Constitution but also owning its chief architect, Bhimrao Ambedkar. Through folk songs, small gatherings and redressal of daily life issues, the Bheels, and many other communities, are increasingly finding meaning in the Constitution.

The Bheels form small groups of volunteers and reach out to communities to prompt conversations around the Constitution, preambular values and address problems by invoking constitutional principles.

Also Read: India’s democracy goes beyond the last mall in Noida. Rural feudal rich are feeling the pinch

Indigenisation of the Constitution

Another such group operates out of Jodhpur and is led by youth from the Kalbelia community—a tribe of snake charmers left to scramble on the margins after the enactment of the Wildlife Protection Act 1971. It is interesting to see how these communities—about whom there is hardly any discourse in mainstream Indian society—are engaging with the Constitution through tribal songs and daily activities.

These youth-led groups are invoking fundamental constitutional principles to address problems of representation, access to ration, birth certificates and proof of residence—issues common among historically nomadic communities like the Kalbelias.

These initiatives are also taken by a network of civil societies, which acts as a capacity builder. They train individuals through cross-learning workshops and community gatherings while acting as knowledge-sharing platforms. Constitutional democracies around the globe are facing an existential crisis, but this community-driven engagement can allow us to reshape the idea of constitutional endurance and see it from the broader perspective of engaging with people who are real custodians of this document. As we celebrate the 75 years of India’s independence, it is crucial to move ahead with the indigenisation of our first document.

Also Read: ‘Not a common tailoring job’—Muslim women in Malerkotla stitch flags for Har Ghar Tiranga

The issue of inaccessibility

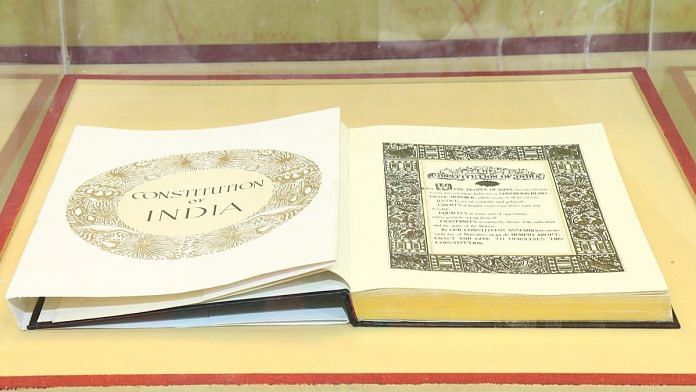

Despite its importance, the Indian Constitution cannot be called accessible. However, it has performed well in the endurance test. Scholars Tom Ginsburg, Zachary Elkins and James Melton argue that the average lifespan of a written Constitution is 19 years. The Indian Constitution has survived almost four times of what their research suggests.

But is this survival the sole reason for such endurance? Professors Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Sujit Choudhary and Madhav Khosla argue that Constitutions persist for a variety of reasons. One of the most important reasons is that it provides space for the settlement of elite aspirations while including groups that were previously excluded and sidelined. However, literature on the endurance of the Constitution does not take into account the issue of civic engagement. As important as it is to them, the common person’s interaction with the Constitution is limited at best.

For instance, a Constitution Connect survey conducted across 93 schools in India found that only 33 schools practised reciting the preamble or engaging with the Constitution in morning assemblies. This is despite a clear government mandate on reciting the national anthem in school assemblies. While students do engage with the Constitution in their political science courses, it is not from a perspective of practice.

Also Read: Independence not result of Congress efforts & satyagraha alone — Hindu Right press lauds RSS role

A paradigm shift

British constitutional scholar Ivor Jennings called the Indian Constitution a “lawyer’s paradise” because of the complex language and phrases it has adopted. Jennings’ assertion isn’t wrong. The lexical complexity of the Constitution has kept its values and principles away from the common people. In the last 75 years, neither the State nor the civil society has endeavoured to take the Constitution to the people. However, after 2014, we have witnessed increased engagement.

In 2015, the Forum for Popularising the Constitution of India began hosting public events in multiple languages on Constitutional issues. Gradually, civic organisations like the Centre for Law and Policy Research began curating texts on the Constitution, while those like Constitution Connect began working in regional languages to make the text more accessible. Academics like professor Tarunabh Khaitan and lawyer-researcher Surbhi Karwa have curated online videos and podcasts to disseminate knowledge of constitutional theories to the masses.

Recitation of the preamble and carrying copies of the Constitution have emerged as popular means of dissent in recent years, especially witnessed during the anti-CAA protests between 2019 and 2020. These efforts were restricted to non–State actors until the Kerala government started efforts for constitutional literacy. In January, the Kollam district panchayat, district planning committee and the Kerala Institute of Local Administration took the initiative to impart basic knowledge of the preamble and fundamental rights.

Supporters of constitutional literacy initiatives argue that acquaintance with the State’s power allows individuals to perform the role of constitutional guardians. Christopher Dreisbach in his book, Constitutional literacy- A Twenty-First Century Imperative, says that the “knowledge of (the) Constitution (is) sufficient to invoke it properly”. These invocations strengthen the role of citizens as constitutional guardians. Thus, as India completes 75 years of independence, we must push to make the Constitution simple, jargon-free and most importantly, accessible.

Rajesh Ranjan is a Samta fellow. He is also co- convenor of the legal aid and awareness committee at National Law University, Jodhpur. Views are personal

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)