Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is delighted that his gamble has paid off. After decimating Israel’s proxies—Hamas and Hezbollah—and substantially weakening Iranian air defences through airstrikes last year, Netanyahu was convinced this was the most opportune moment to target Iran’s nuclear and missile programmes. The challenge was to get US President Donald Trump to join him in the exercise.

And Trump did. In the early hours of 22 June, the US targeted three nuclear locations in Iran: Fordow, Natanz (another enrichment site), and Isfahan (a uranium conversion site). After declaring that the nuclear sites had been “totally and completely obliterated,” Trump added, “NOW IS THE TIME FOR PEACE.”

Hours later, Iran responded with a missile strike on US forces at the Al Udeid air base in Qatar, causing no damage or casualties. The move appears to have been a choreographed exercise, reminiscent of Iran’s retaliation in January 2020 after Quds Force General Qassem Soleimani was killed in Iraq. Meanwhile, Trump has declared that ‘a full and complete ceasefire’ will be in effect shortly, though neither Iran nor Israel has confirmed it yet.

Iran’s nuclear programme—a long journey

Iran’s nuclear journey has been long and tortuous. It began under the Shah’s regime in the 1950s with a civil nuclear cooperation agreement signed with the US, and the first research reactor went critical in 1967. Since then, the nuclear programme has been seen as a symbol of scientific progress and a source of nationalist pride.

Iran became an original state party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1970 when it entered into force, placing all its activities under International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards. The Shah embarked on an ambitious civil nuclear power generation programme, signing cooperation agreements with Germany and France. Siemens began work on the Bushehr power reactors (2×1200 MW) in 1975 but later withdrew. The plants finally went online in 2011 with Russian assistance.

After the Islamic Revolution, nuclear activity came to a standstill as the clerical regime saw it as a source of Western influence. However, sometime in the 1990s, opinions changed, and nuclear research activities were gradually revived. By then, nuclear controls had tightened, curbing exports of enrichment and reprocessing technologies, though these remained permitted under the NPT. Iran revived its civilian nuclear power projects and also began establishing a clandestine enrichment facility. It received assistance from the AQ Khan network as well as from China to develop capabilities across the entire nuclear fuel cycle. In parallel, Iran began developing missiles.

In 2002, nuclear activity was exposed by a group of Iranian exiles. It became clear that regular IAEA inspections had failed to detect the clandestine programme. Negotiations began in 2003, initially with the three European powers and later including the US. These collapsed when President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took over, and starting in 2006, Iran was subjected to successive UN Security Council sanctions. By this time, Iran had established its first enrichment facility at Natanz.

Around that time, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei issued a fatwa against nuclear weapons, describing them as un-Islamic. The general assessment is that while the fatwa was respected, Iran pursued the technical capabilities to become a nuclear threshold state. As recently as 26 March, the US Director of National Intelligence stated in an official briefing to Congress: “The Intelligence Community continues to assess that Iran is not building a nuclear weapon and Supreme Leader Khamenei has not authorised the nuclear weapons programme that he suspended in 2003.” This assessment has also been affirmed by Rafael Grossi, Director General of the IAEA.

Also read: Iran’s brutal regime is facing a reckoning. Consequences of US attack will go beyond Tehran

Can Iran remain a nuclear threshold state?

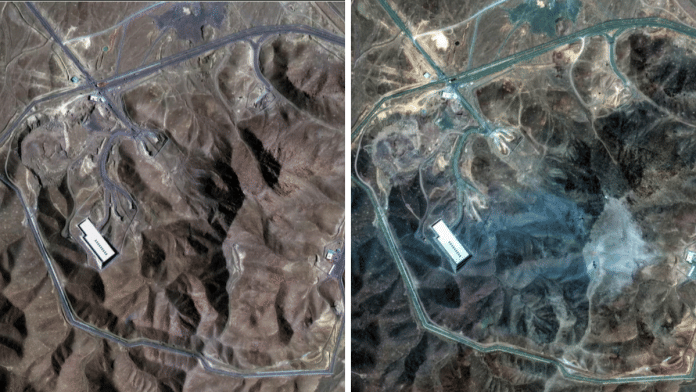

In 2009, a hitherto secret underground enrichment facility at Fordow was exposed. Israel and the US cooperated in the 2008 Stuxnet covert operation, which destroyed a large number of centrifuges before the Iranians discovered the computer malware in 2010. Thereafter, Iran expanded its uranium enrichment programme, leading to talks that culminated in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015.

Under the JCPOA, Iran accepted rigorous IAEA inspections and permanent camera monitoring. However, beginning in 2019—one year after the US withdrew from the JCPOA—Iran began scaling back its adherence to additional inspection measures, observing only the basic safeguards mandated by the NPT. On 31 May, an IAEA report revealed that Iran had rapidly increased its stockpile of 60% enriched uranium to 408 kg, enough to be further enriched relatively quickly to weapons-grade (90%) levels, and sufficient for approximately 8–10 bombs. On 12 June, the IAEA declared—for the first time in over 20 years—that Iran was non-compliant with its nuclear obligations under the NPT. Israel, which is not a party to the NPT, struck on 13 June, and the US followed on 22 June.

All major nuclear sites—including the research reactor in Tehran, enrichment facilities at Natanz and Fordow, the heavy water reactor at Arak, the fuel fabrication and research reactor at Isfahan, and the suspected military site at Parchin—have been repeatedly targeted. There are questions about the extent of damage to the centrifuges, particularly at the underground sites at Fordow and Mt. Kolang Gaz La near Natanz. The whereabouts of the 408 kg of 60% enriched uranium also remain a matter of speculation. IAEA monitoring has not detected enhanced radioactivity around the sites. Further details will only emerge after the IAEA resumes inspections, contingent on renewed talks between Iran and the US and the prospect of a new deal.

Meanwhile, Iran’s leaders are likely to conclude that remaining a nuclear threshold state is a dangerous position, especially when the adversary is a nuclear-armed state. The Ukraine war and the use of nuclear sabre-rattling further underscore this lesson. Other countries in Asia are also likely to draw their own conclusions, revealing the growing fragility of the global nuclear regime.

Rakesh Sood is a retired diplomat who served as Ambassador to Afghanistan, Nepal, and France. He also served as India’s first Ambassador – Permanent Representative to the Conference on Disarmament at the United Nations in Geneva and later as PM’s Special Envoy for Disarmament and Nonproliferation. He tweets @rakeshnms. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)