The collapse of the Indian economy during the Covid-19 crisis has been big – bigger than elsewhere and larger than the headline number for the non-farm private sector — and this is when we only have weak data for the informal sector, which was the hardest hit.

What we need is a variety of data to examine the extent of the GDP fall, the potential green shoots and what the future might hold.

Though consumer sentiment and investment decisions remain pessimistic, economic activity is gradually resuming, as data on electricity consumption, Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) registration, bank lending and GST collections show. Yet, with some variation, all these are lower than where they would be normally, and so it may be necessary to accept and adjust to this ‘(s)lower’ pace of growth this year. If there is no de-growth in September, using electricity consumption and GST collections as two ends of the spectrum, it is reasonable to estimate that double-digit growth in the second half of financial year (over the second half of last year) is necessary, if the whole year is not to see a decline in GDP.

Also read: Govt needs to be scared out of complacency & Q1 contraction could do that, Raghuram Rajan says

The fall

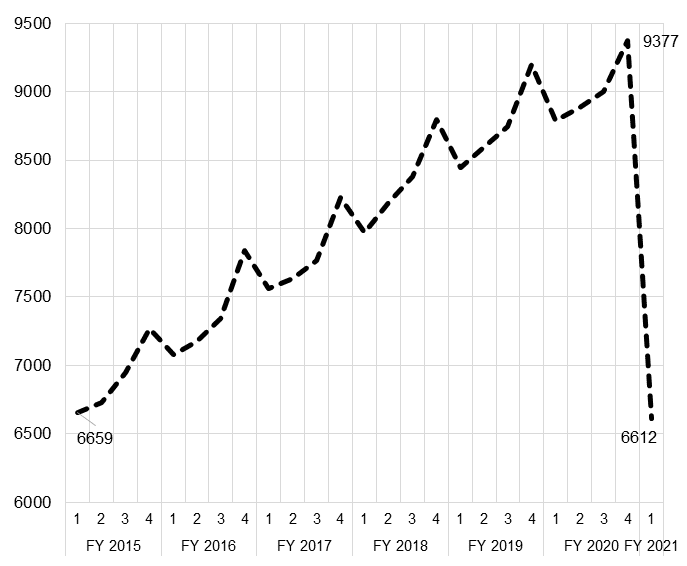

Our per-capita income now is the same as when Prime Minister Narendra Modi first took office in 2014.

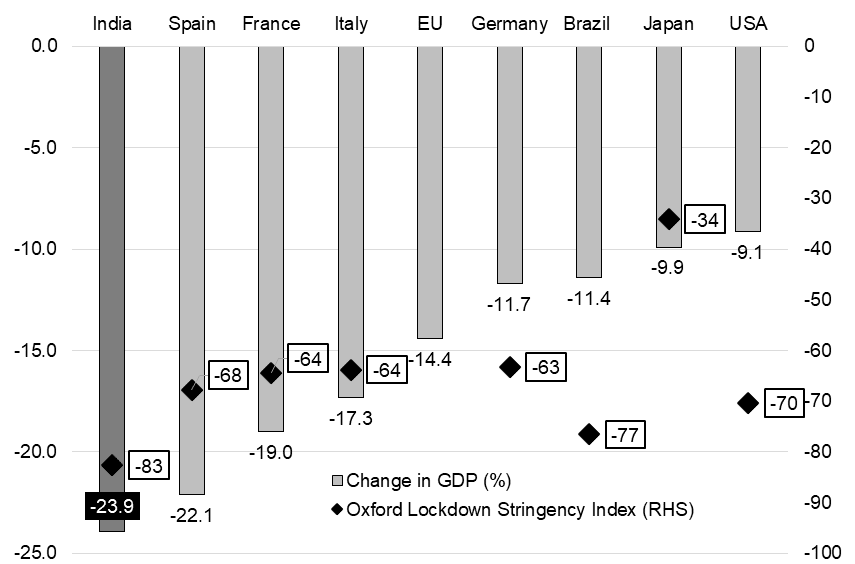

That, as shown in Figure 1, is the implication of the 23.9 per cent fall in GDP during April-June 2020. Other major economies too fell off the cliff, but India fell the furthest, as shown in Figure 2, but it is not unusually large, given that Spain and France had similar declines in GDP. This is not surprising given that India basically went into national quarantine for all of April, quite different from the kinds of lockdown seen in Europe. In the US and Brazil, lockdowns have been regionally decided, while in Japan, the lockdown was used in a limited manner, and focus was much more on contact tracing.

Figure 1: Monthly per capita GDP (constant 2011-12 prices) (1Q FY 2015 to 1Q FY 2021)

Source: NSO (population interpolated within the year)

Figure 2: Change in quarterly GDP (constant prices) from the same quarter of the previous year and lockdown index

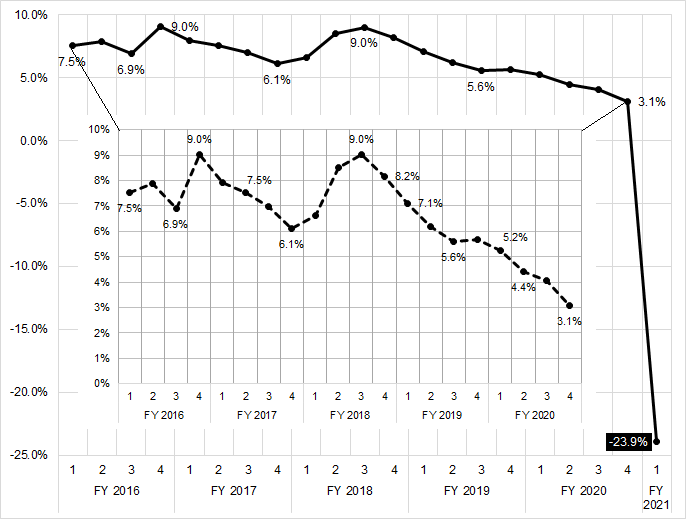

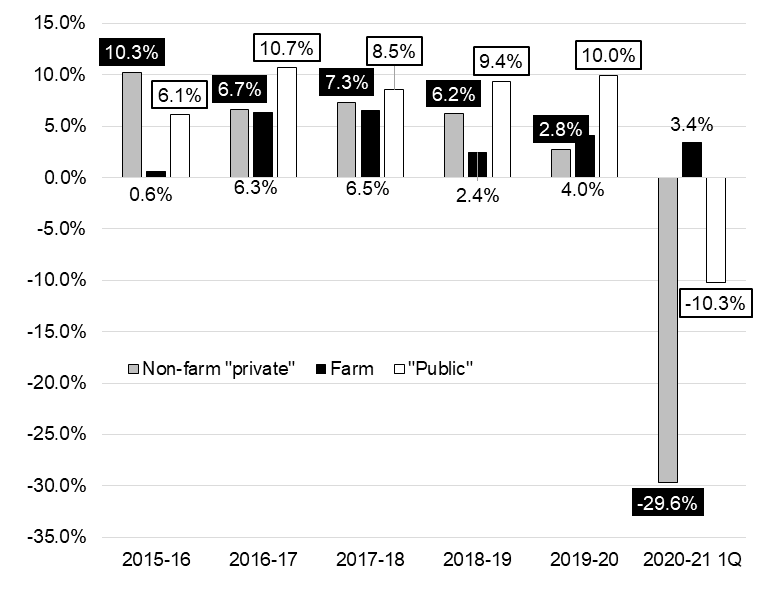

Figure 3 shows that this decline comes on the heels of a growth rate that was steadily declining ever since a brief recovery from that fateful November day in 2016, when PM Modi announced demonetisation. In recent years, this decline has been even more pronounced for the non-farm private sector, which, as shown in Figure 4, fell almost 30 per cent compared to the first quarter 2019-20. This is important because the declining growth rate and income has affected people’s expectations and their financial reserves against such an event.

Figure 3: Change in quarterly GDP (constant 2011-12 prices) from the same quarter of the previous year

Figure 4: GVA growth by broad components at constant 2011-12 prices (FY 2016 to 1Q FY 2021)

The surprising element is the 10 per cent fall in ‘public’ GVA, but this aggregate includes not just public administration and defence but also other services, that form more than 55 per cent of the aggregate. So, even though government final consumption did rise by 16.4 per cent this quarter, a 30 per cent fall in other services, in line with the overall trend, could result in an aggregate 10 per cent fall in this component.

Also read: Indian economy is heading for a K-shaped recovery and it won’t be a pretty sight

Consumption and investment

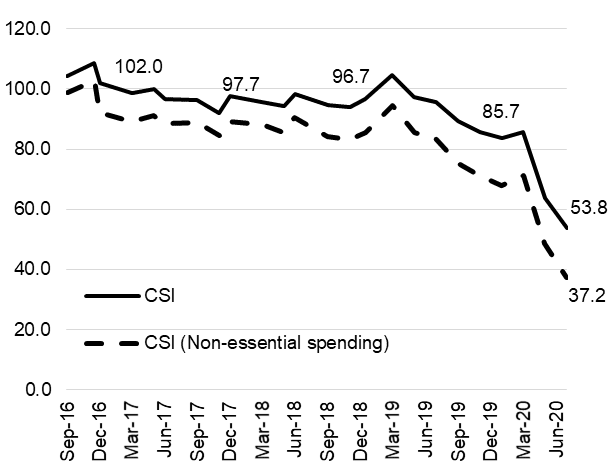

Not only is the drop in GDP large, consumption fell by even more, at 26.7 per cent. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI)’s Current Situation Index has taken a nosedive as seen in Figure 5. If one adjusts for the fact that increased spending may reflect higher prices of essentials, and replaces total spending in the index with the more discretionary measure of non-essential spending, the fall in sentiment is even sharper.

Figure 5: Current situation index

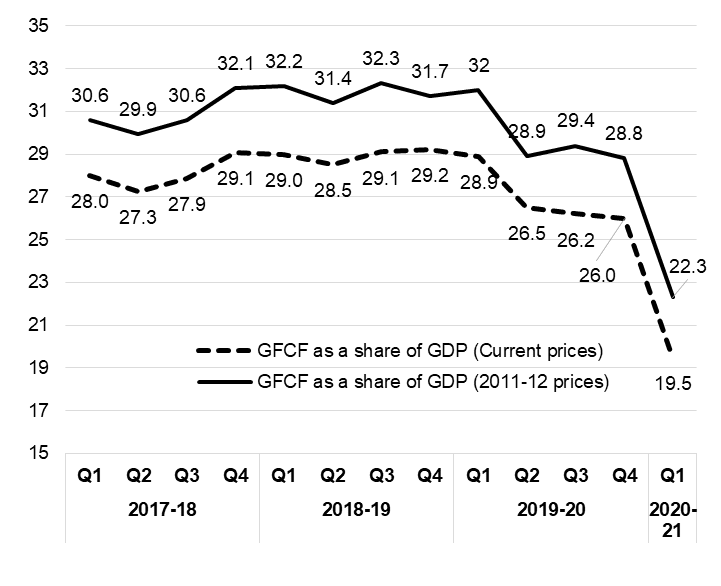

Investment was almost cut in half, falling by a near catastrophic 47 per cent. Capital formation, as a share of GDP, fell below a fifth of GDP, as seen in Figure 6, levels last seen when three-fourths of the Indian population had not yet been born. Investment needs faith in the future, and while that has been wavering for some time, the Covid-19 crisis appears to have pushed it over the pessimistic precipice.

Figure 6: Gross fixed capital formation as % of GDP

Also read: How fiscal regression can force Modi govt to take sub-optimal economic decisions

Green shoots?

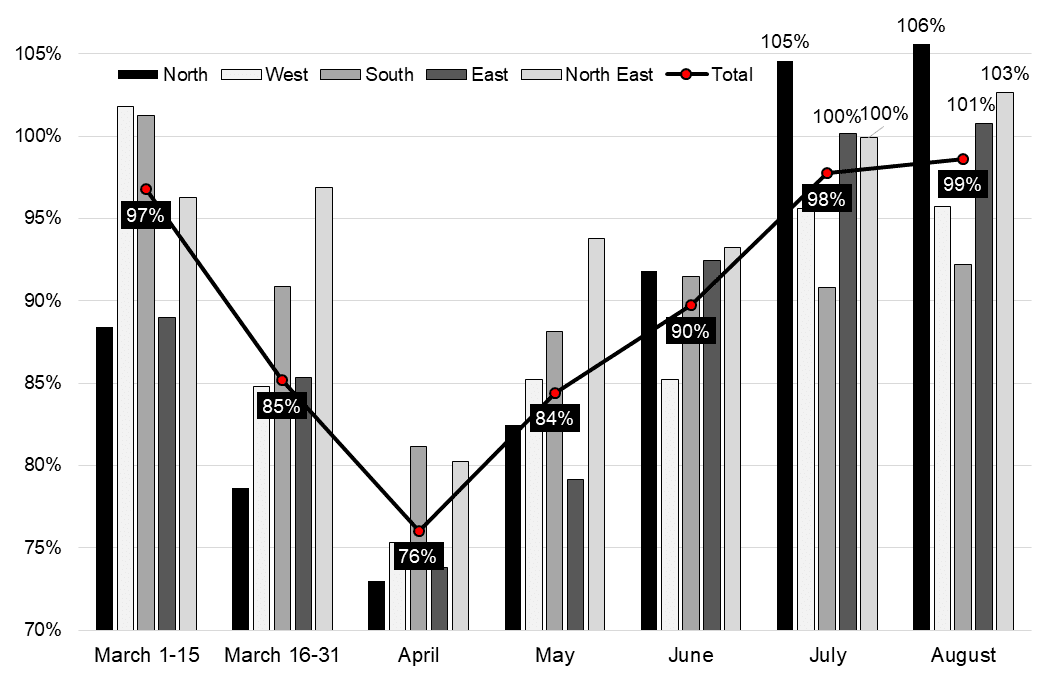

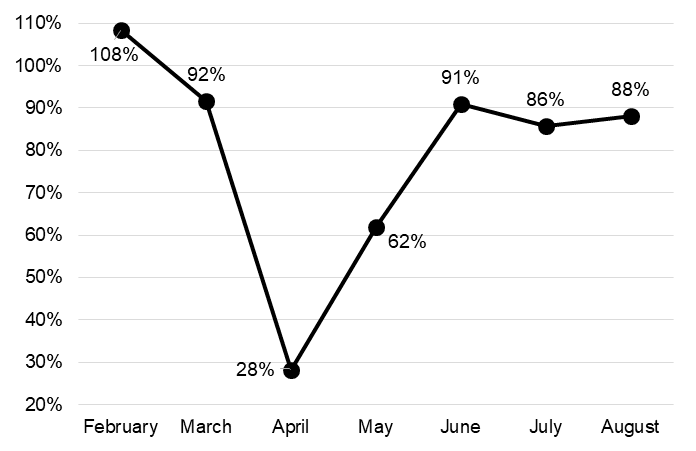

But, what of the immediate future? The picture may be rosier, depending on the glasses. Electricity consumption is recovering faster than other metrics, as seen in Figure 7 (comparing month to month, adjusting to keep the same number of weekdays, that is, it does not compare 1 to 30 April 2020 to 1 to 30 April 2019 but 3 April 2019 to 2 May 2019). But even for electricity, growth for the rest of the fiscal year has to be near 9 per cent for national consumption to be the same this fiscal as the last.

Figure 7: Change in national electricity consumption

Over April to June, aggregate fall was 17 per cent (much less than that of GDP). There are regional patterns (may be weather related), with a shallower drop and a slower recovery in the southern region and a sharper fall but quicker rise in the northern belt. But, August has been the same as July and that is not a hopeful sign.

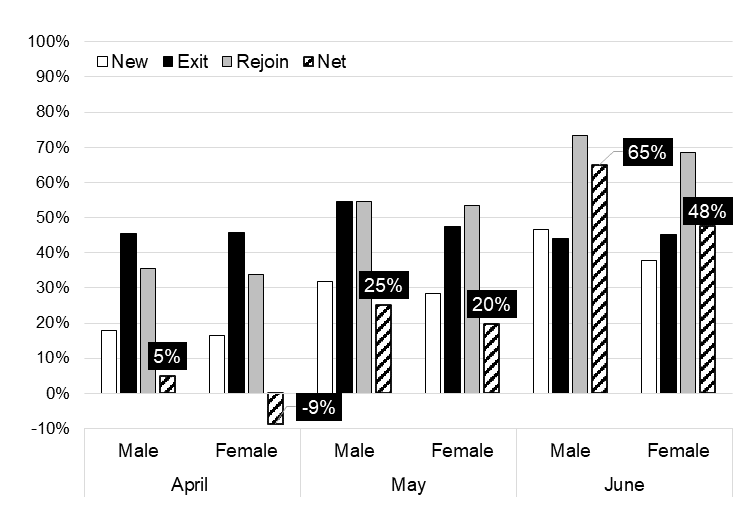

Organised employment, as seen in the EPFO registrations in Figure 8, is also recovering, but remains well below last year’s levels, with a sharper fall and relatively slower return of the women to the organised workforce. So, the recovery, such as it is, is relatively slow and gender imbalanced.

Figure 8: Changes in EPFO registrations (% of corresponding month in 2019-20)

This is also seen in GST collections, which fell 72 per cent in April but has now recovered in August to be around 88 per cent of August 2019, as seen in Figure 9, which shows GST collections in 2020 as a proportion of the corresponding month in 2019. This is to be expected, given that a number of services are still not operational, especially in the travel, hotel, and restaurant and entertainment sector. Overall spending, too, is likely to take time to recover, given the large income shock in Figure 1. Given the sharp shocks in April and May, second half collections have to grow almost 25 per cent over last year just to maintain last year’s levels.

Figure 9: Changes in GST collections (% of corresponding month in 2019-20)

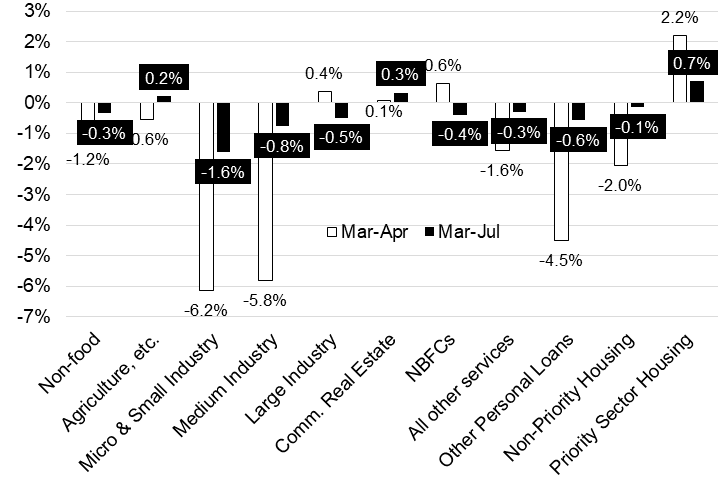

Concomitantly, bank credit growth is tepid. Figure 10 shows the growth of bank credit by major sectors over March to April (during the lockdown) and then March to July. A negative number means that the gross credit to that sector has gone down since March. While the negative number in April is expected, its persistence till July indicates a hesitant recovery. Large industry data may not reflect poor outlook, rather a rebalancing of borrowing away from banks and towards the market, but the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) have been hit hard.

Figure 10: Bank credit growth by select sectors

Also read: Agriculture can’t rescue Indian economy, it can only be a safety net

The world outside

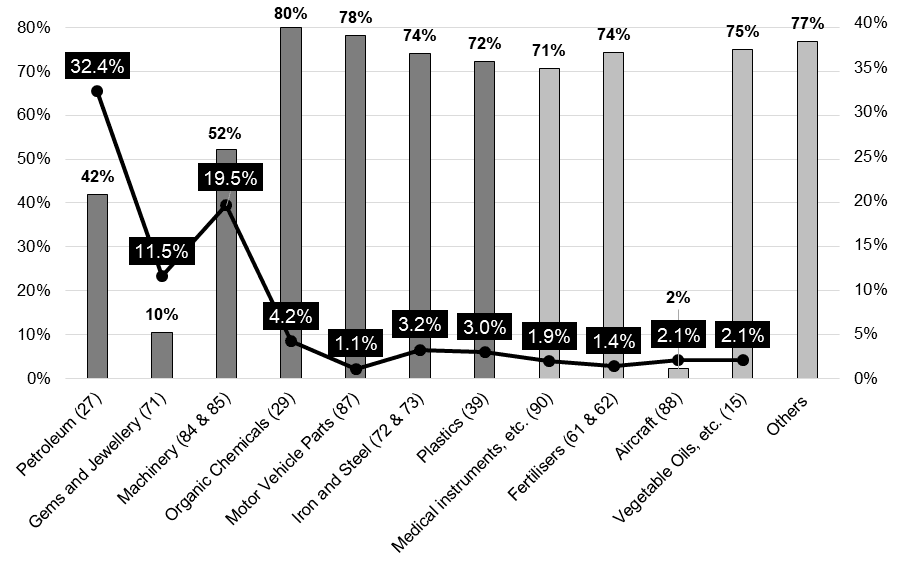

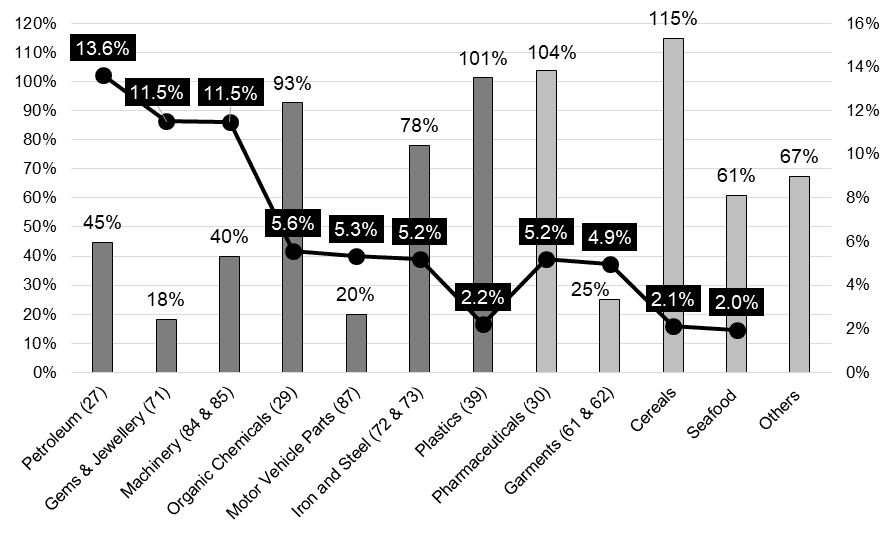

The final question is whether one can decipher any positive patterns in the external sector that compensate or at least mitigate the sharp domestic fall. During April-May (figures for non-oil exports and imports in parenthesis), India’s goods exports were $29.5 billion ($26.3 billion), that is, about 56.4 per cent (58.2 per cent) of the annualised average of two months for 2019-20, and goods imports were $39.3 billion ($28.6 billion), about 49.7 per cent (53.4 per cent) of the average for last year.

Figure 11 shows that this was driven by sharp fall in the country’s top three major imports, two of which are directly related to our export production, viz. petroleum, gems and jewellery and the third, machinery, which is partially linked. This is evident when one examines the export performance in Figure 12, which shows a sharp decline in the same top three categories. Other export categories showing substantial declines are motor vehicle parts and garments. As a whole, gems and jewellery, garments, motor vehicle parts and machinery, among the most labour intensive export oriented manufacturing sectors, have taken a huge hit.

Figure 11: Import changes by commodity

Figure 12: Export changes by commodity

However, overall (including services) exports for April to June exceeded overall imports by about $10 billion, generating a trade surplus of 2.8 per cent of GDP (in 2011-12 prices, 2.1 per cent in current prices) for the quarter. This indicates that services exports, usually around 40 per cent of total exports, continued to do well during the lockdown period, and will form a larger share of exports in this quarter. This accords well with the anecdotal evidence of the speed with which work from home was instituted in the information technology and business process outsourcing (BPO) sectors, allowing them to maintain activity during the lockdown.

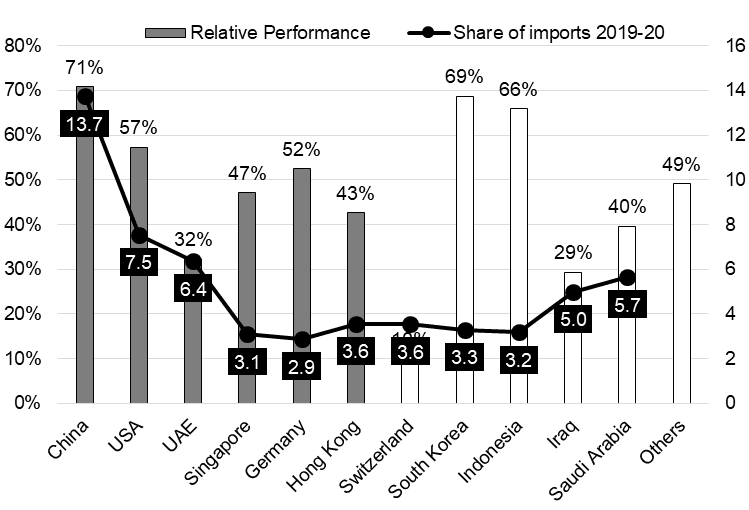

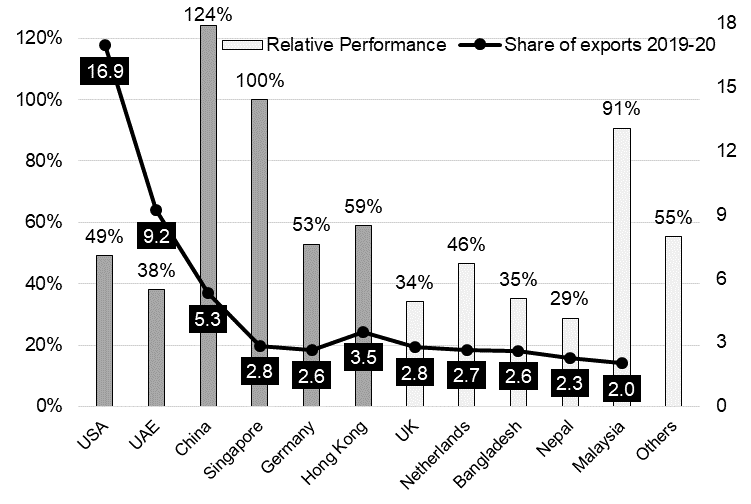

The country composition of trade in Figure 13 shows that links to China remain strong – with imports at 71 per cent of the two-month average of last year. In Figure 14, it is seen that exports to China were 24 per cent more than what could be expected in an average two-month period last year. In the last 10 years, China’s contribution to the goods trade deficit has gone from about 6 per cent to around one-third. China’s share in exports went up from 5 per cent in 2019-20 to 12 per cent in April-May 2020 and its share in imports rose from 14 per cent in 2019-20 to 20 per cent. The structure moved more towards exports of iron and steel, and imports of organic chemicals. At a time when economic activity is muted, the resilience of these links indicate a relatively (compared to other trade linkages) strong linkage with China.

Figure 13: Import changes by country

Figure 14: Export changes by country

Trade with top trading partners like the US, Germany, the UK, and the Netherlands has fallen more than with Asian counterparts such as Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia and China. It is not clear how strong the hysteresis effect will be, but this could affect India’s trade buoyancy adversely, coming out of the pandemic.

Also read: India’s economic growth has seen a consistent fall, Gods cannot be blamed for everything

Future foretold?

The sharp reduction in income in the first half has diminished precautionary savings of many households and forced others to borrow to meet essential expenditure. Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), an independent think tank, estimates a substantial loss in salaried jobs, with cuts continuing in July. Workers in the informal sector, especially in urban services, such as transportation, accommodation, food and events, were worst hit and many migrants among them have returned home. Their remittances, which boosted rural consumption, have disappeared. Neither can we expect the festive season to provide respite, given the continuance of the pandemic. Thus, we would be lucky if consumption returned to last year’s levels in the second half. Furthermore, given this outlook for consumption and given that industry is already working below capacity in many sectors, it is unlikely that investment can be at last year’s levels either.

Externally, our larger markets have been disproportionately affected, as have our major labour intensive export sectors such as garments, gems and jewellery and motor parts. There is no indication that petroleum exports are likely to come back strong, given the pace of recovery elsewhere. In addition, there is likely to be disruption associated with decoupling from China, post Galwan.

Thus, double-digit growth seems rather optimistic, given the lack of any demand drivers, domestic or external. While government expenditure did increase significantly, it would need to more than double in order to compensate for the losses in other demand sources thus far, if a decline in GDP is to be averted. This is fanciful, given poor tax revenues, and even poorer appetite for borrowing. Besides, government expenditure cannot substitute for low private demand in many areas such as informal services and small manufacturing, where there is limited role for public demand.

But, if GDP declines this fiscal, as appears inevitable, policy actions that are taken this year could well determine if 2021-22 becomes a boom year. If this drying up of demand kills a large number of MSMEs, there may be some rationalisation and growth potential for the remaining units, but that is likely to be swamped by their fear of bankruptcy, which will reduce the pace of their expansion.

Similarly, the return of the migrant workforce would be conditional on the probability of securing employment in the city, which will largely increase with the resumption of employment growth in the informal sector. Some migrants will return, with job promises based on social networks, but many fewer are now able to absorb the cost of surviving in the city while looking for work. If there is a sharp contraction in the MSMEs, these jobs will be lost and the resulting fall in domestic remittances could affect rural demand negatively, even if farm growth is robust.

Even within the public sector, the Modi government’s stance on federal fiscal relations, which so far appears tightfisted and shortsighted, will impact the confidence of the state governments to spend, who are responsible for well over half the total government expenditure.

Also read: Whatever happened to the aspirational Indian?

What will work

India has become significantly less open from the time its trade/GDP ratio exceeded 50 per cent earlier this decade. This post-Covid world is a time to engage and recover lost ground, as global value chains are being reorganised in a world that, leaving aside political considerations, is worried about excessive dependence on a single large source like China. This is a time to remove constraints of finance, power, logistics, import restrictions and duty structures that hold back our exporters, build a true Atmanirbharta or self-reliance, and not withdraw into an inward-looking mindset of self-sufficiency.

Structured loan guarantees and a small wage subsidy paid directly to the worker can both support MSMEs and concomitantly ‘formalise’ their workforce, bring back migrant workforce and restart remittances to rural areas. Investing in logistics, capping power costs to industry and cleaning up duty structures and removing import restrictions that hold back sectors such as synthetic garments will boost competitiveness sharply. A public works programme focused on wiping off the infrastructure maintenance deficit in our cities can work like an NREGS insurance in rural areas. These are not implausible or unaffordable, and can bring India back to double-digit growth. But it requires the Modi government to approach economic policy with the same boldness with which it instituted the national lockdown, not the tepid timidity that is currently on display. Will it?

The author is senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, Delhi. Views are personal.