Uttarakhand now joins the ranks of states that have imposed statutory restrictions on the purchase of agricultural land by outsiders, including Himachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Assam, Sikkim, Meghalaya, Manipur, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and the scheduled areas of West Bengal, Odisha, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh.

However, what constitutes ‘land,’ who is an ‘outsider,’ and what are the ‘exceptions,’ along with the authority that can grant exemptions, have always been mired in legal, political, cultural, and economic contests. These questions have played out in multiple states, including Jammu and Kashmir, where land ownership laws underwent changes following the state’s reorganisation into the Union Territories of J&K and Ladakh in August 2019—which I will take up later in this column.

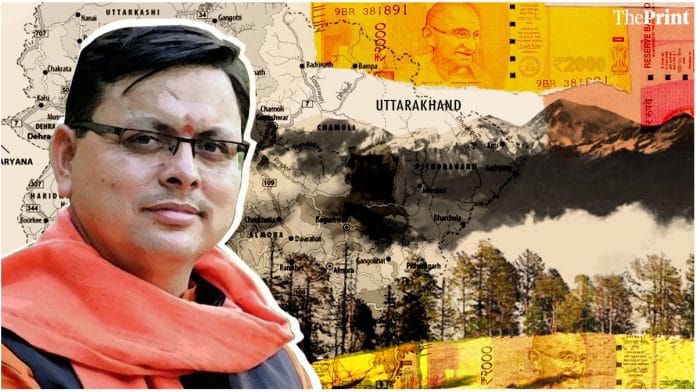

Last month, while introducing the Uttarakhand (Uttar Pradesh Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act, 1950) (Amendment) Act, Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami described it as the fulfilment of the long-standing demand and sentiment of the people of the state. According to him, “this historic step will protect the resources, cultural heritage, and rights of the citizens of Uttarakhand” and play a significant role in maintaining the “original identity” of the state.

This statement, however, deepened the rift between highlanders and plainspeople, with the latter opposed to the provisions of the law. This perhaps explains why the plains districts of Haridwar and Udham Singh Nagar have been excluded from its ambit.

Also Read: Uttarakhand UCC regulating live-in relationships has a positive side too

How land ownership evolved in Uttarakhand

India is perhaps unique in its classification of land into several categories and subcategories. While most land in non-municipal areas is agricultural, within municipal areas, it is further designated as residential, mixed-use, commercial, or institutional land.

Landholding patterns and revenue settlements during British rule were primarily based on the Zamindari, Ryotwari, and Mahalwari systems. There was no concept of land ceiling; the state was primarily interested in collecting the highest possible revenue. Therefore, large tracts of land—especially in East India and the United Provinces (as Uttar Pradesh was then called)—were under the Permanent Settlement or Zamindari system. In the Ryotwari system, which prevailed in the Madras and Bombay presidencies, land revenue was paid directly by the farmer-cultivator. In the Mahalwari system, the village head was responsible for revenue collection, but land ownership remained with individual farmers.

However, the British continued the Mughal-era practice of granting revenue-free (Muafi) land to religious endowments or as a mark of recognition to individuals who had rendered exceptional service to the state.

Before proceeding, let me highlight two distinct features of the hill districts, which were part of UP until Uttarakhand was created in 2000. First, unlike other parts of the province, an estimated nine-tenths of hillmen were hissedars (partners) in land—cultivating proprietors with full ownership rights. Henry Ramsay, the commissioner of Kumaon Division in 1856-1884, described them as “probably better off than any other peasantry in India”. This had already been recognised by Commissioner George William Trail in his land settlement of 1822-23, which demarcated and documented the boundaries of forest land, farming land, and revenue villages without infringing the forest rights of local communities and allowing them to continue their forest-based subsistence practices.

His successor Ramsay introduced the category of ‘forest land’, over which the state exercised complete control. However, after several agitations and protests, certain customary rights were restored, allowing local communities to graze cattle and collect forest produce, including firewood for personal domestic use.

After Independence, the hill districts also came under the provisions of the UP Zamindari Abolition Act, 1950. When Uttarakhand was carved out of UP in 2000, there was a demand to introduce a Himachal-style legislation restricting land purchases by non-residents. Instead, the ND Tiwari government amended the UP Zamindari Abolition Act, capping land purchases for bona fide residential purposes at 500 square metres. This was cut to 250 square metres by the BC Khanduri government in 2008, only to be liberalised again by the Trivendra Singh Rawat government in 2018.

Entitlement for outsiders—the special case of J&K

Before we discuss the 2025 legislation, let us take a look at the provisions regarding land entitlement across the country, including J&K, which had the most restrictive provisions until the abolition of Article 370 on 5 August 2019.

Until then, the former state could define ‘permanent residents’ and create special provisions for them. However, for all the hype about every Indian now being eligible to buy land in the new Union Territory, the modified J&K Land Revenue Act continues to restrict the purchase of agricultural land to those classified as ‘agriculturists’. The term refers only to those who personally conduct farming in J&K. However, modifications do allow the Centre to notify other categories of people who may be granted rights to buy agricultural land in the future.

Furthermore, conversion of agricultural land to non-agricultural use—which earlier required permission from the Revenue Minister—can now be approved by the district collector. This could facilitate the establishment of residential apartments, commercial establishments, and industrial zones, but land use, especially agricultural land, will continue to be monitored.

Notably, the changes made to J&K’s land laws do not apply to the Union Territory of Ladakh.

Restrictions in Nagaland

Article 371A of the Constitution was incorporated when Nagaland was granted statehood in 1963. Under this amendment, the Centre cannot pass any laws for Nagaland regarding land ownership and transfer.

This exclusive authority has seen the Nagaland government create laws restricting the purchase of land to only the “indigenous inhabitants” of the state.

This restricts any outsider from purchasing land in the state—and technically, any non-indigenous resident as well. In recent years some amount of land has been acquired by outsiders as a result of loan/security defaults, which has led to opposition in the state.

Himachal: Provisions, exceptions, exemptions

Himachal Pradesh received statehood in 1971. A year later, it passed the Himachal Pradesh Tenancy and Land Reforms Act, which placed restrictions on land purchases by outsiders.

Per Section 118 of the Act, land transactions—whether in rural or urban areas—were restricted to ‘bona fide residents’ of the state, defined as those who have resided there for 20 years or more. Non-Himachal women married to bona fide residents were given a special exemption from this rule.

All land outside designated municipal areas and under forest cover was classified as agricultural, even where it was not being used for this purpose. This effectively put it out of reach for even bona fide residents unless they were agriculturists.

However—and this is where there is a catch—if there was an existing built-up structure on the land, a non-agriculturist resident of the state could purchase up to 500 sqm for residential purposes or 300 sqm for commercial use with permission from the Revenue Department.

As such, the bottom line is that it takes twenty years for an outsider to become eligible to purchase land for residential purposes. For the rest, the only option is to approach the HP Urban Development Authority.

Over the years, exceptions have been made for certain industrial projects, such as hydroelectric power. Investors looking to purchase land for such uses can get special permission from the state government.

Sikkim: Pre-merger rules prevail

After Sikkim’s merger with India in 1975, a new provision—Article 371F—was inserted into the Constitution, allowing Sikkim to retain laws enacted during the Chogyal era. Based on this, the state has continued to restrict the sale of land and property to outsiders.

Except in designated municipal areas, only Sikkimese residents can purchase property. In tribal areas, only members of the community can undertake land transactions. The only opening for outsiders is to buy land for the establishment of industrial units or private universities.

Special provisions for Arunachal and Mizoram

Arunachal Pradesh does not derive its restrictions on land ownership from a special constitutional provision but from longstanding customary rules. These rules have traditionally not been interfered with by the state government, let alone the Centre. Under these customary rules, technically, no individual could even have rights over property in the state, whether residents or non-residents.

Individual property rights for indigenous people were finally recognised in a 2018 law. However, outsiders and non-tribal residents still cannot own property in the state.

Mizoram, meanwhile, also has rights under Article 371G to restrict ownership and transfer of land in non-tribal areas, which is at the discretion of the Mizoram Legislative Assembly.

Also Read: UCC was debated more in the Constituent Assembly than in Uttarakhand. Why it’s a problem

Regions under Fifth and Sixth Schedule

Both these schedules of the Constitution allow the respective states to make special provisions for land ownership and entitlement.

The Sixth Schedule provides for the creation of autonomous councils in tribal areas of the Northeast, which have imposed restrictions on outsiders buying land. The Fifth Schedule applies to tribal land in Jharkhand, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh.

Tomorrow, this column will take up Uttarakhand’s new land legislation in greater detail.

Sanjeev Chopra is a former IAS officer and Festival Director of Valley of Words. Until recently, he was director, Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration. He tweets @ChopraSanjeev. Views are personal.