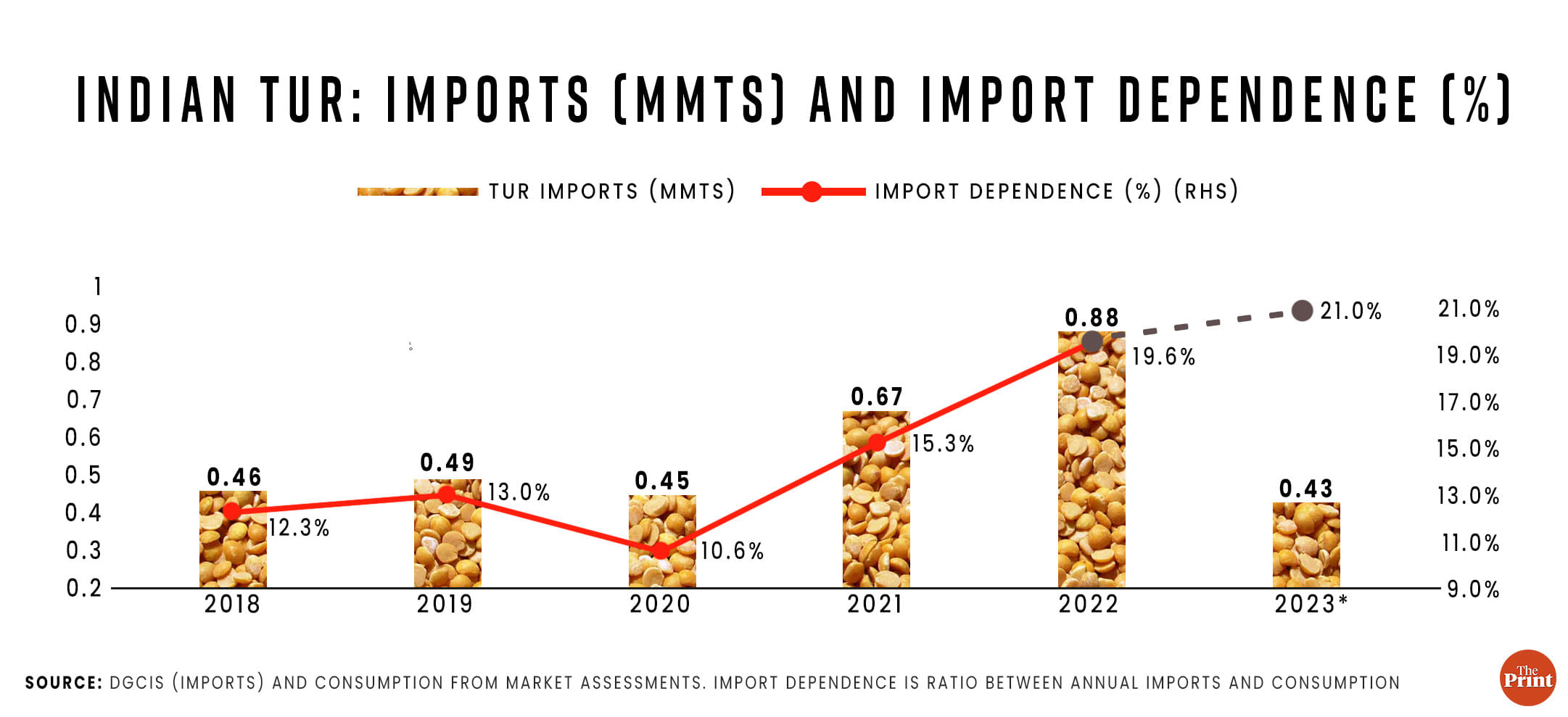

In less than three years, India’s dependence on imported tur, pigeon pea, has doubled. The pulse’s import dependency ratio was about 10 per cent in 2020 and it increased to 20 per cent in 2022. It is predicted to go up to 21 per cent in 2023. Indian tur has been losing its steam. It was the second most-grown pulse crop just 10 years back but has fallen to the third position today. It is not that we are consuming less tur, but imports are increasingly filling the domestic supply gap.

African countries like Mozambique, Malawi, and Sudan, are now growing tur for export to India. Currently, India is grappling with smaller tur stocks and double-digit inflation, but many tur-exporting African countries are trying to profiteer from the situation. Indian tur needs attention before it is too late.

Indian pulses basket

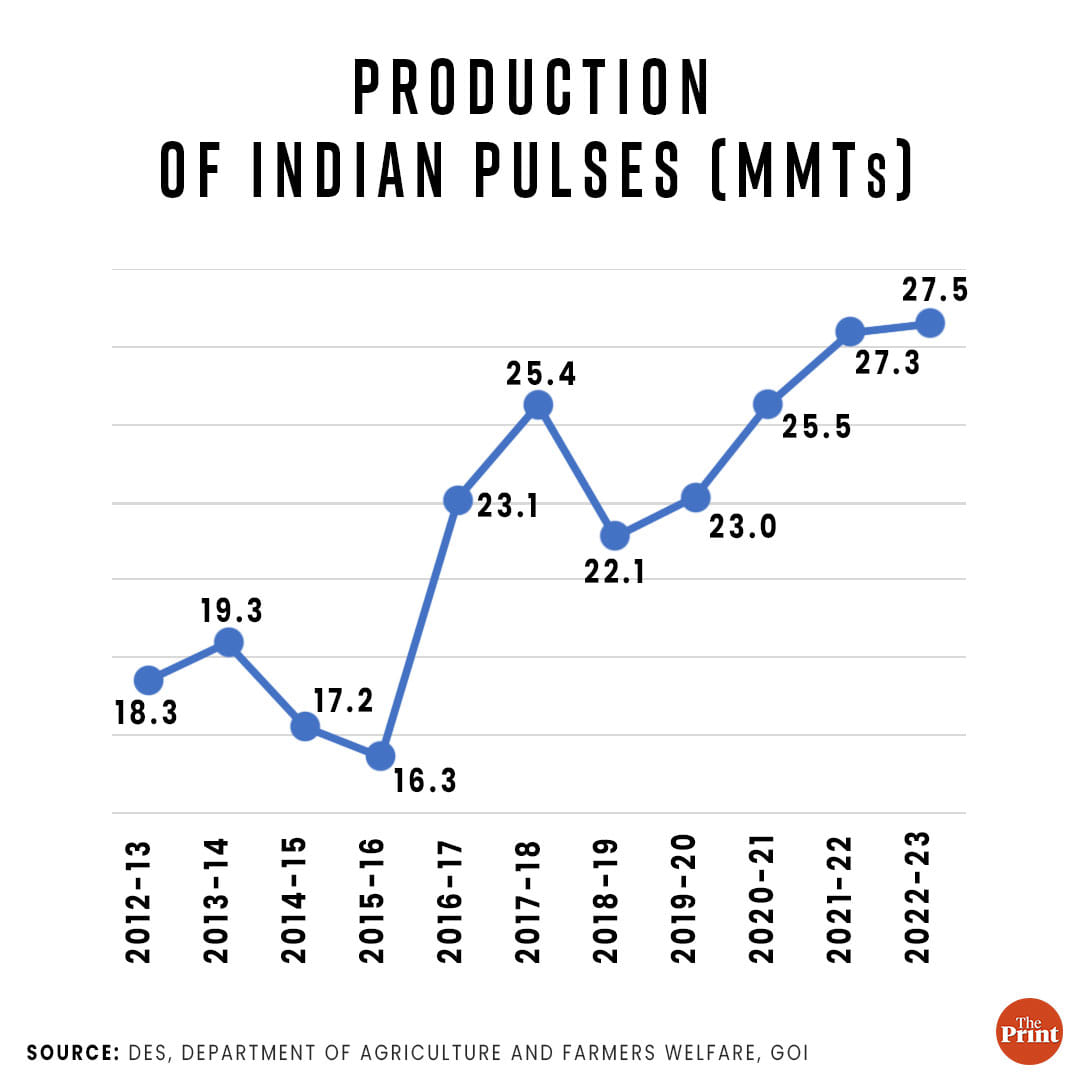

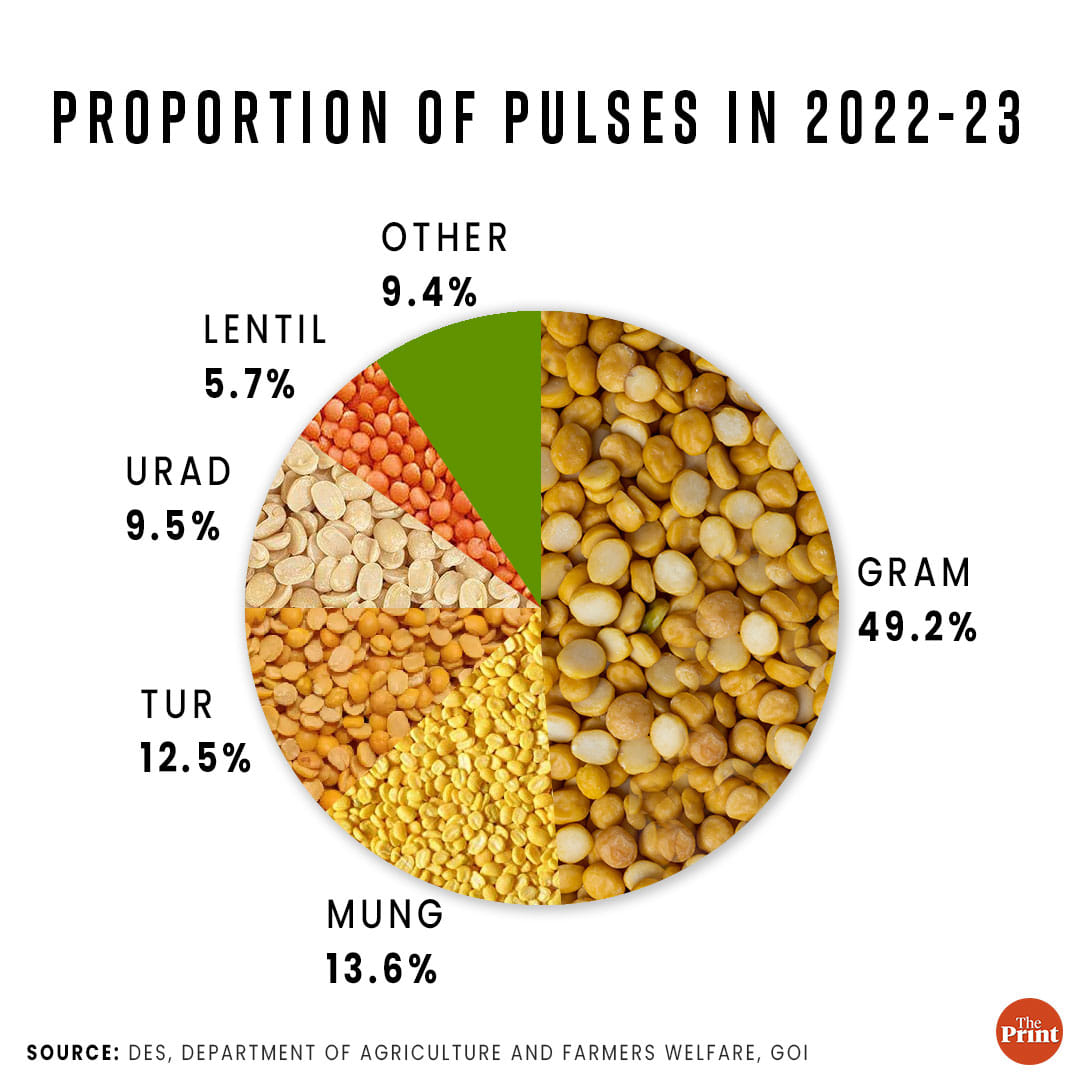

As per GOI’s third advance estimate, India produced about 27.5 million metric tonnes (MMTs) of pulses in 2022-23. Close to half (49 per cent) of this was gram (including both kabuli chana and chickpea/bengal gram). About 14 per cent was mung, about 12.5 per cent was tur, and less than 10 per cent was urad. Among the five main pulse crops, lentil or masur is the smallest.

Mung has shown exceptional growth between 2012-13 and 2022-23. While the total pulses crops grew at 4.2 per cent, tur grew at 1.3 per cent, and mung at 12 per cent.

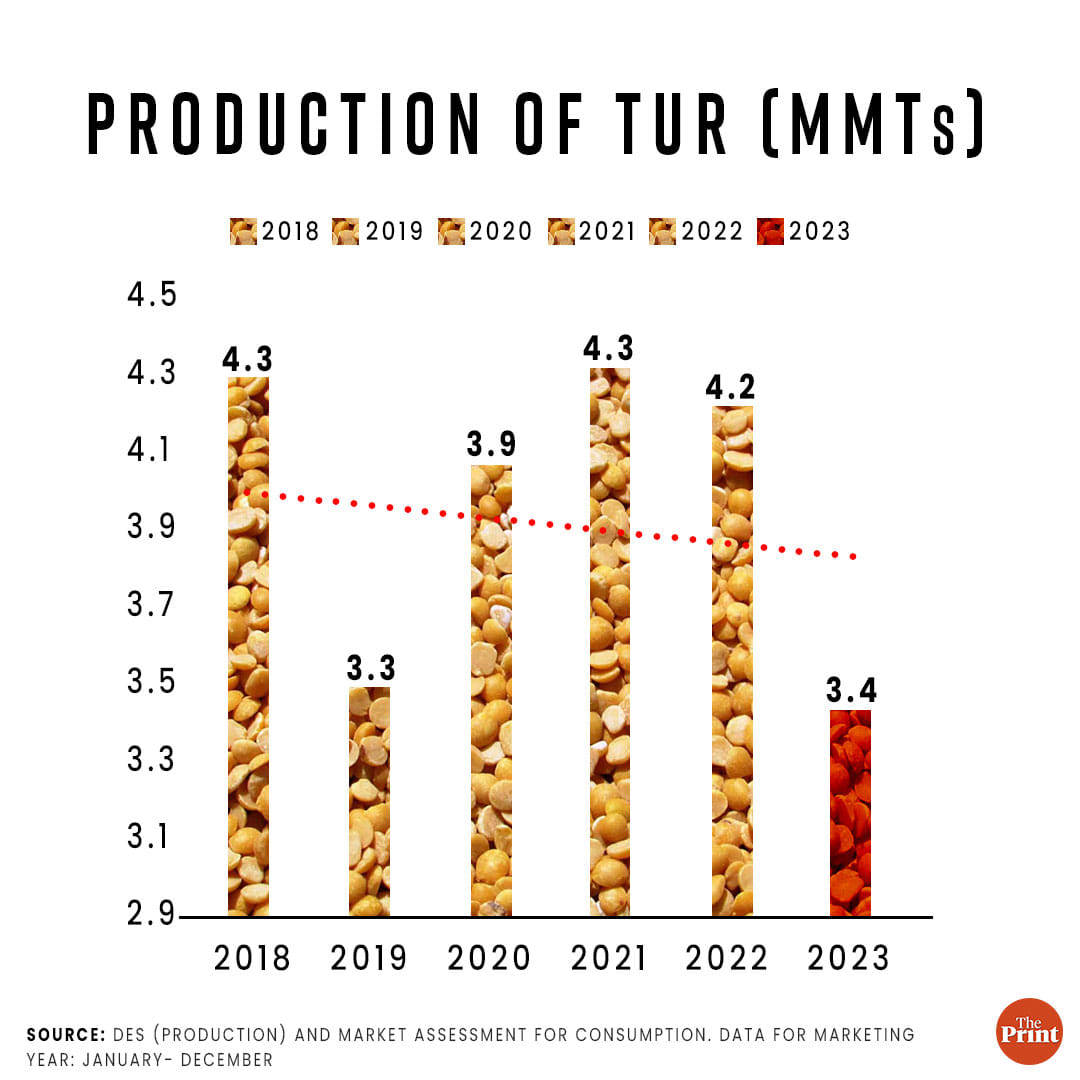

According to official estimates, tur production in 2022-23 (sown in June/July 2022 and harvested in January/February 2023) was about 3.4 MMTs. This was lower than the previous year (4.2 MMTs) and only marginally above the lows of 3.3 MMTs in 2019. Since 2018, the Indian tur crop production trend has been going downward.

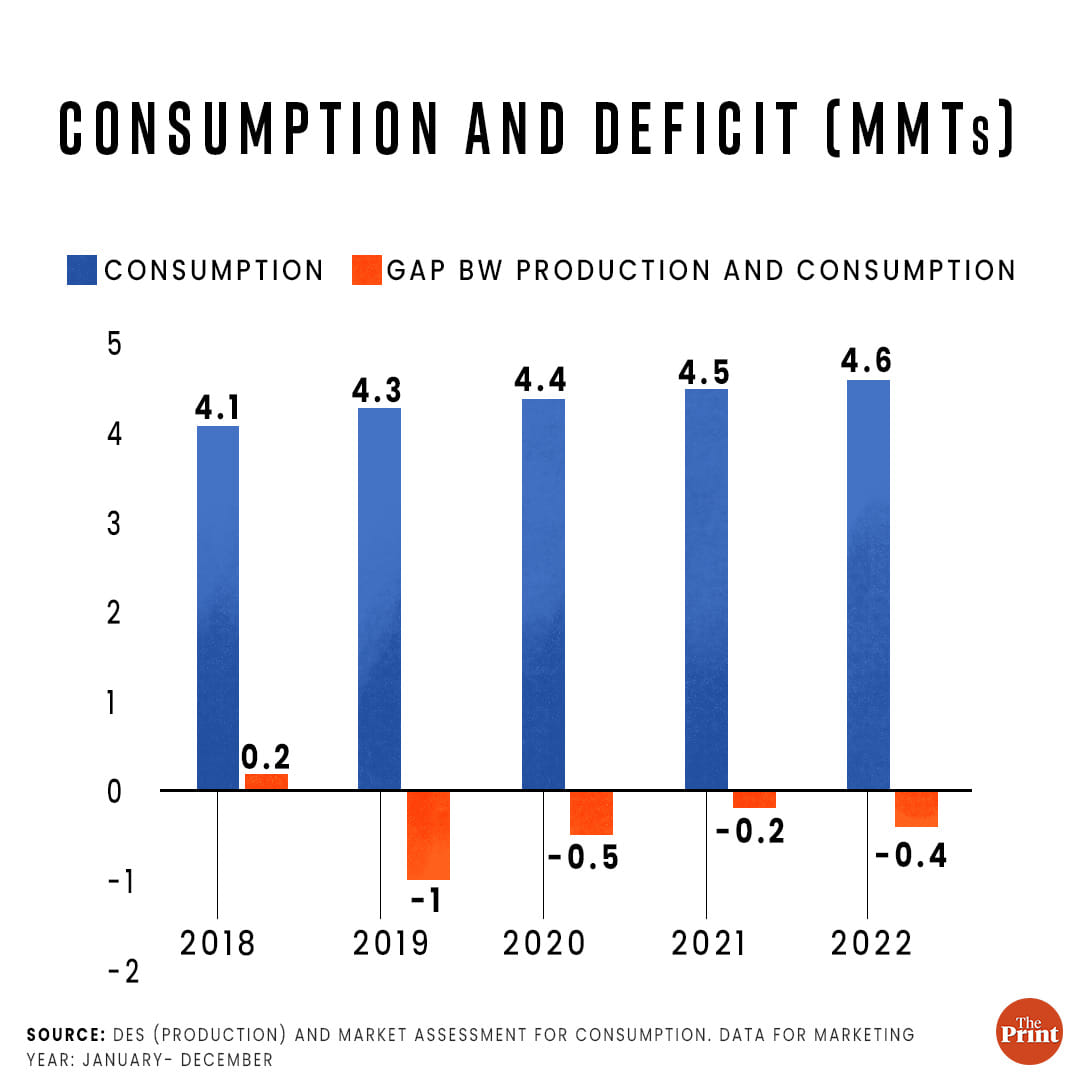

Meanwhile, India’s tur consumption has been rising: it is up from 4.1 MMTs in 2018 to about 4.6 MMTs in 2022. This implies that the deficit has been growing. From a surplus of 0.2 MMTs in 2018, there was a deficit of about 0.4 MMTs in 2022.

The deficit is reflected in high tur dal retail prices. From about Rs 109/kg in August 2022, tur is currently retailing at about Rs 138/kg, according to the Department of Consumer Affairs. In terms of the Consumer Price Index, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation recorded that tur dal witnessed an annual inflation rate of 34 per cent in July 2023.

Also read: What’s common between Modi & Manmohan govt on agriculture? Distrust of futures markets

Rising imports and MOUs

Amid rising consumption and volatile production, tur imports are rising. They averaged about 0.47 MMTs between 2018 and 2020 (Figure 3). They touched about 0.7 MMTs in 2021 and rose to 0.9 MMTs in 2022. This year (until July 2023), imports have already touched 0.43 MMTs and are predicted to further rise to about 0.9 MMTs.

India is the largest producer, consumer and importer of pulses. Foreseeing gaps in India’s own ability to supply enough tur and urad, the Modi Government did well and signed MOUs with Mozambique, Malawi and Myanmar in 2021 for the import of pulses. While minimum quantities to be procured annually were fixed, there was no cap.

The crisis now

While the existing crop is smaller, the next in the pipeline (one sown in the fields currently) is assessed to be small too. In the ongoing kharif season, acreage under tur trails previous years. As of August 25 2023, the area under tur was 42.11 lakh hectares, which was about 2.3 lakh hectares below last year and about 4.2 lakh hectares below the normal area. Irregular rains in key tur growing areas of Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, and the open import policy are discouraging farmers from growing the pulse.

Assessing lower Indian tur production this year, big corporates in African countries may well like to profiteer from the situation. There is news about imposing export duties to restricting supplies even under MOUs.

Also read: India has a dal problem – open import policy is hurting prices and farmers

What now?

By increasing dependence on imports, India may be stifling its own markets. If India is serious about Atmanirbharta in pulses, the Government has to take proactive actions and plan for the medium and long term.

- Fix the MSP correctly: Tur is a long-duration crop — sown in June/July (kharif season) and harvested in January-February. Mung is also sown during kharif, but it is a short-duration crop, sown and harvested within four months. MSP of mung is Rs 8558/quintal whereas that of tur is Rs 7000/quintal. There is a growing preference of farmers towards mung. Till 2018, the gap between the MSP of tur and mung averaged about Rs 200/quintal, however, since 2018-19, the gap jumped to an average of about Rs 1240/quintal. Yield of tur in some states is higher than mung but a large gap in returns (among other things) is causing diversions of area away from tur. This gap needs to be corrected.

- Trade-off between inflation and farmer incentives- The government has to walk a thin line to ensure adequate availability of affordable food for consumers and ensure that farmers are remuneratively compensated. Open imports and provisions of the Essential Commodities Act (ECA) support consumers but hurt the farmers. In one of our ongoing studies, we have found evidence of gram and mustard farmers holding back stocks of their harvested crops to sell at a later stage to leverage future arbitrage opportunities. Apart from the traders, provisions of ECA also hurt such farmers who are then unable to realise good prices for their stored crops. GOI’s export and trade-restricting actions hurt a crop’s entire value chain that takes years to build. However, access to affordable food is critical for the country and therefore, beyond a certain inflation rate, it appears trade restrictive policies are called for. But the moot question is how much is the country’s inflation-tolerance-level? This requires much deeper research.

- Climate change and weather resilience: Erratic monsoon patterns, the eruption of new pests and a 6-month-long crop are disincentives for tur growers. The country needs a shorter-duration variety of tur and the need for developing climate resilience in crops cannot be overemphasised.

- Implement earlier recommendations: In 2016, the Government had set up a committee under then Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian. Its report ‘Incentivising Pulses Production through Minimum Support Price (MSP) and Related Policies’ has several useful recommendations that need to be acted upon.

Policymakers have to feel the pulse before it is too late. It is tur this year, could be gram next year. A visionary and agile policy is the need of the hour.

Saini is an agricultural economist and CEO, Arcus Policy Research and Hussain is former Secretary Agriculture, GOI. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)