I often find myself as the lone woman in a sea of men when navigating the Indian bureaucracy. Despite the flattering colours of my saree standing out in a room of greys, blues, and blacks, I can’t help but ponder the conspicuous absence of other women of my generation.

The data confirms that there is a glaring gender gap in positions of authority, especially in the civil services. I rely on the Indian Administrative Service Officers dataset from the Trivedi Centre for Political Data (TCPD) at Ashoka University to examine the representation of women in the elite Indian Administrative Service (IAS). This comprehensive dataset offers insights into the demographic profile of IAS between 1950 to 2020, covering variables like age, gender, state of residence, educational background, and other pertinent characteristics.

Since open-access cross-sectional data providing a complete profile of women across civil services, and their recruitment years remain unavailable, I have used the TCPD data to gauge the representation of women in the IAS as indicative of broader trends in civil services. According to analysis, the proportion of women officers recruited directly to the IAS was barely 5 per cent. However, an apparent rising trend starts to show up:15 per cent in the 1970s, 25 per cent in the 2000s, and 27 per cent by 2020.

One may argue that, with one-third of legislative seats now reserved for women, the fact that 27 per cent of total IAS officers are women is a significant stride forward. However, progress remains insufficient for several reasons.

Factors to low representation

First, the current representation likely fails to accurately reflect the diversity of women in India. Women in the bureaucracy predominantly originate from New Delhi, where more than 35 per cent of selected IAS officers are women. However, Uttar Pradesh, which has produced the largest number of IAS officers since 1950, only has 10 per cent women officers. Conversely, there are disproportionately fewer women IAS officers in states such as Bihar, Rajasthan, Odisha, and Madhya Pradesh.

Second, while there may be relatively higher representation in elite positions like the IAS, we lack insight into the number of women employed in lower administrative ranks that are essential for governance and policy implementation at the grassroots. This gap in understanding hinders our ability to judge true progress in gender representation throughout all echelons of the administrative system.

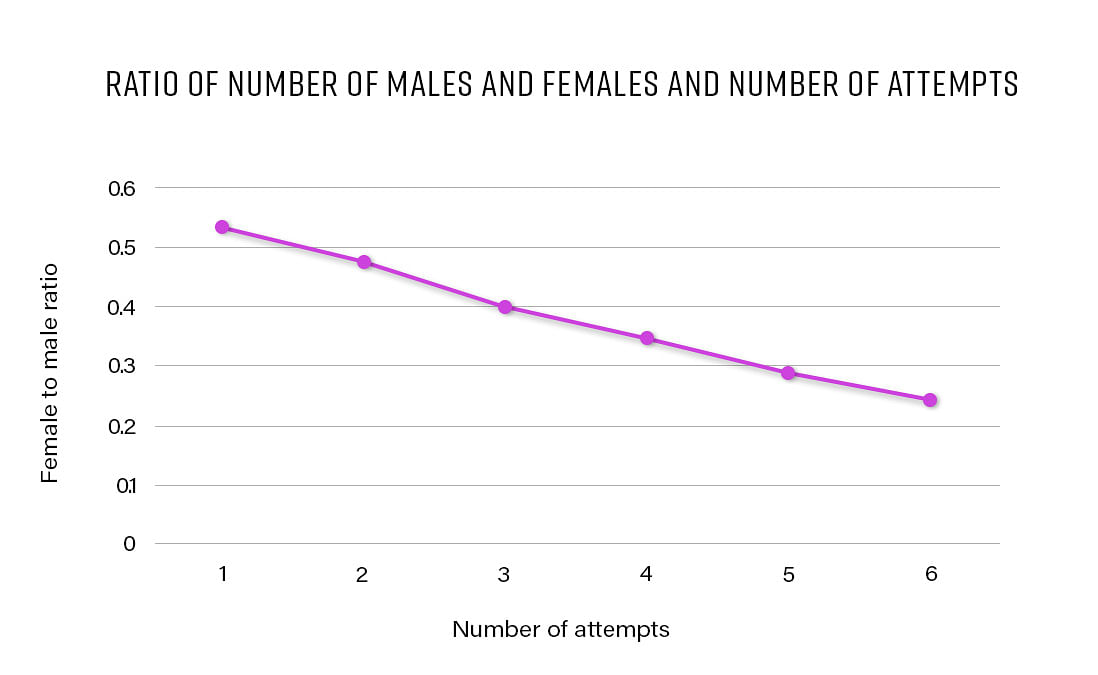

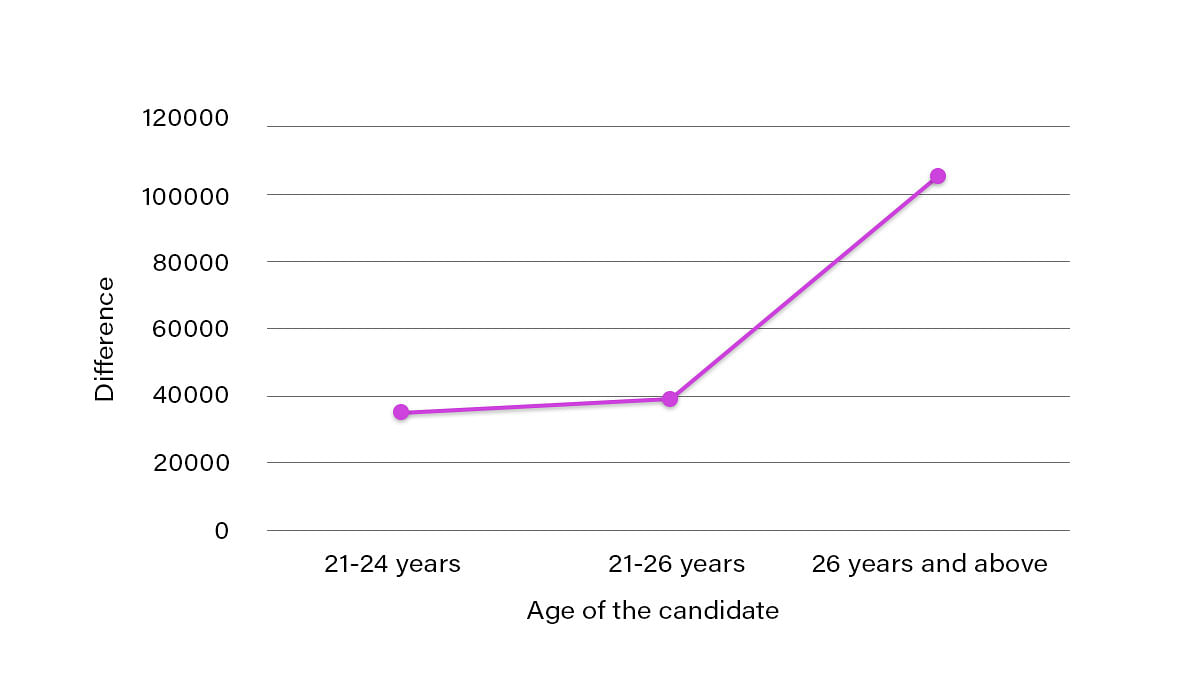

What are the contributing factors to the low representation of women in the bureaucracy? They exist on both the demand and supply sides. Supply-side factors include fewer women applying for civil services. According to the 72nd Annual Report published by UPSC, in 2021, 7,02,674 male candidates applied for the exam. Women candidates were less than half of that number—3,33,730. The graph below shows that this difference between male and female candidates tends to widen with age. This implies that not only do fewer women apply for the civil services examination, but they also tend to withdraw from the race as they age.

Preparing for this exam is a lengthy process. The UPSC report states that a candidate requires an average of three attempts, spanning over 4.5 years of intense preparation, to succeed. There are also significant financial costs involved. Even after investing time and money, the odds of attaining a position in the civil services are extremely low.

Additionally, Indian parents frequently view the opportunity cost of investing in their daughter’s education as greater than that of their son, owing to socio-cultural variables surrounding a daughter’s marriage and her standing in the family. Given this, they may hesitate to make such an investment in their daughter’s career. With little or no encouragement from parents, the woman may decide to not even consider civil services as a career choice.

Another significant factor lies in women’s perceptions of their ability to clear the exam, which can be influenced by one’s belief system or how they perceive their abilities in comparison to societal expectations. Research underscores the critical role of self-perception in determining one’s likelihood of success. For instance, an experiment by Spencer et al. in 1999 found that when both male and female students with strong mathematical skills faced a challenging test, women performed worse.

However, when informed beforehand that stereotypes about women’s mathematical abilities didn’t apply to that specific test, they performed as well as men. This phenomenon may also apply to women considering civil services exams, as they may internalise biases against their abilities, leading to fewer attempts or premature withdrawal from preparation. However, the opposite also holds: When women are assured that such negative biases are unfounded, they are more likely to persist and ultimately succeed.

Also read: Women breaking barriers to enter bureaucracy. But UPSC numbers don’t tell the whole truth

Inclusive workplace policies

Demand-side factors, such as hiring bias against women, may not significantly contribute to the low representation of women in civil services. Data suggests that the barrier to women’s entry into civil services primarily lies in the early stages of the exam process.

According to the UPSC report, the success rate of women in the final stage of the exam—the interview—is 55 per cent. It is significantly higher than the success rate of men, which is 38 per cent. This indicates that once a woman decides to appear for the exam and progresses to the interview stage, she is more likely to be selected compared to a man. Despite the interview stage involving maximum human interaction and thus potential bias, women candidates, on average, outperform male candidates. This strongly suggests an absence of discrimination on the demand side.

Moreover, the workplace policies of the Indian government are quite gender sensitive. They are specifically tailored to address the challenges faced by women who bear the double responsibility of work and home. For instance, the women employed in the central government in India are entitled to fully compensated maternity leave of 26 weeks. Being one of the longest maternity leave duration in the world, it exceeds the leave entitlements of women in countries such as Denmark and Switzerland, which are globally recognised for their high rankings in the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) gender inequality index.

Women working in the central government also have the option to take childcare leave, which is two years long. This leave can be taken at any point during their employment, as long as it is before their child or children reach the age of 18. Gender-inclusive policies should ideally empower women to view civil services as a viable career choice.

Given that the underrepresentation of women in civil services appears to stem mostly from supply-side factors, it’s imperative to implement policies that target these root causes. They must challenge stereotypes, provide greater access to resources and opportunities, and foster an environment where women feel empowered to pursue their aspirations without fear of gender bias or discrimination. Only then can we truly harness the full potential of women in shaping the future of governance and policy-making in India.

With the immense potential of Indian women, I remain hopeful that soon, I’ll be joined by a myriad of women in sarees, each breaking barriers and making her mark in the corridors of power.

Kanika Dua is an IRS(GST and Customs) and is currently serving as Deputy Director in Delhi. She has recently finished MSc in Development Economics from the LSE as a Chevening Scholar. The views expressed are personal and do not represent any organisation/institution.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)