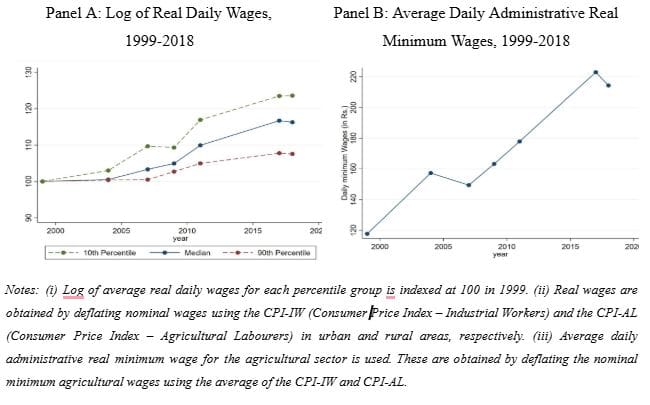

Wage inequality in India has decreased by 35% over the two decades from 1999 to 2018 (National Sample Survey (NSS), 1999, Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), 2018). This decline is driven by substantial wage growth among low-income workers. Real wages at the 10th percentile increased by 23.61%, outpacing the 7.56% rise observed at the 90th percentile, leading to a narrowing of income disparities (Figure 1, Panel A).

During the same period, the median real minimum wage across Indian states increased by 70% (Figure 1, Panel B). In recent research (Khurana et al. 2025), we examine whether and to what extent the increase in minimum wages explains the observed decline in wage inequality.

Figure 1. Changes in real wages and real minimum wages, 1999-2018

Minimum wage setting in India

In most economies, minimum wage policies primarily target low-wage workers through a national or state-wide wage floor, as seen in the US and the UK. In contrast, India’s industry and occupation-specific minimum wage-setting extends beyond the lowest-paid workers. The Minimum Wage Act 1948 empowers Indian states to fix minimum wages for workers in scheduled employment categories – with approximately 1,700 classifications. This results in significant complexity, with more than 1,000 distinct wage rates often operating within a single state for different job categories.

Our study uses changes in minimum wages for unskilled agricultural workers. These wages serve as a benchmark for two reasons – they are the lowest minimum wages and face fewer ambiguities in enforcement, although challenges persist due to informal contracts; and they are highly correlated with changes in minimum wages in other non-agricultural job categories.

A concern with minimum wage setting by states could be that these respond to the macroeconomic situation in a state. However, we do not find a significant effect of state-level factors like sectoral distribution on states, poverty rate, inflation, etc. on minimum wage changes across states. This ameliorates the concern that our findings are driven by other state-level economic factors correlated with minimum wages.

Data and methodology

Our analysis draws on NSS Employment and Unemployment Survey (EUS) data (1999, 2004, 2007, 2009, 2011), PLFS data (2017, 2018), and minimum wage data at the state level from the Labour Bureau. We use a ‘two-way fixed effects’ model – controlling for unobserved time-invariant factors at the district level and macroeconomic yearly factors – to assess the role of changing log of minimum wages on log wage received by an individual, by the wage quintile to which an individual belongs to. We also implement a ‘border discontinuity design’ by restricting the analysis to neighbouring districts across state borders and exploiting variation across districts along the border belonging to different states.

Findings

We find that a 1% increase in minimum wages has the largest impact on the lowest wage quintile in both rural and urban areas, with rural wages rising by 0.17% and urban wages increasing by 0.22%. The marginal effect reduces for higher wage quintiles, with an insignificant effect on the highest quintile. These results show that minimum wage increases predominantly benefit lower-income groups, with urban areas experiencing slightly higher gains presumably owing to better institutional structures and compliance.

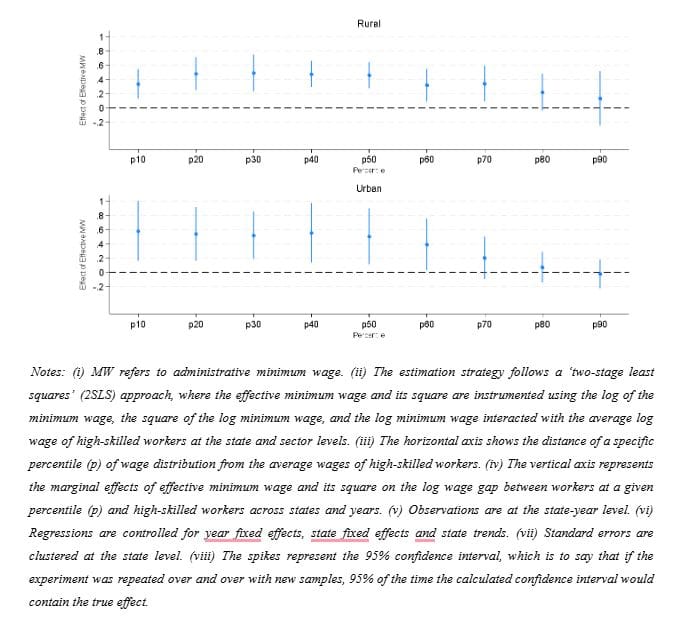

Additionally, we redefine the minimum wage variable to account for its relative position within the local wage distribution. We construct an ‘effective minimum wage’, defined as the gap between the legislated minimum wage and the average wage of high-skilled workers within a state and sector. The impact of variations in the effective minimum wage is assessed on the wage gap between different percentiles of the wage distribution and the average wage for high-skilled workers. This approach accounts for state-level wage differences, allowing us to examine spillover effects and potential non-compliance. Our findings in Figure 2 show that minimum wages have positive spillover effects, impacting wages up to the 80th percentile in rural areas and the 60th percentile in urban areas.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of effective minimum wages on wage percentiles, by sector

Next, we examine the impact on formal and informal workers. Theoretically, minimum wage hikes can increase wages in the ‘covered’ sector (formal workers) while potentially displacing labour to the ‘uncovered’ sector (informal workers), and depressing informal wages. On the other hand, due to the “lighthouse effect” higher wages in the formal sector can empower informal workers to negotiate better pay or use the minimum wage as a fair wage benchmark.

Our findings show that the latter effect dominates – minimum wages increase wages for low quintile workers more than highest quintile workers in both formal and informal sectors, with a stronger impact on formal workers (by 0.27% for formal versus 0.24% for informal in rural areas; and 0.28% for formal versus 0.25% for informal in urban areas). These results show that the minimum wage serves as a reference point for equitable compensation and reduce wage inequality for both formal and informal workers.

We ensure the observed reductions in wage inequality are not driven by external factors through extensive checks. First, we include state- and district-level trends in outcomes, and further augment this by incorporating unobserved heterogeneity at state-year level. We test alternative definitions of inequality, including those based on education and skill, and continue to find that the less educated and low-mid skilled workers gain the highest when minimum wages increase. Reassuringly, the highest educated and skilled workers are not affected by an increase in minimum wages, showing that other state-level factors do not drive the results.

Lastly, we apply two alternative methods of estimation. First, we exploit variation in minimum wage changes over time across two districts that border each other but lie in different states. This is akin to using differential change in minimum wages across contiguous district pairs over time to estimate their effect on prevailing wages. The estimates for urban areas are similar.

For rural areas, we find that the effects are lower for all quintiles by a similar magnitude, thus, effects on wage inequality remain similar. Second, we use the estimation method proposed in De Chaisemartin et al. (2023) when dealing with continuous treatment over time. Our estimates show a significant decline in wage inequality when minimum wages increase by 1% – by 0.13% between the 50th and 10th percentiles of the wage distribution in rural areas, and by 0.28% between the 90th and 10th percentiles of the wage distribution in urban areas.

Also read: Income inequality reducing, one-third tax filers in bottom slab moved up to higher levels since 2014

Discussion

To assess the overall effect on inequality due to the obtained estimates, we undertake a counterfactual analysis. Here, we compare actual wage inequality in 2018 with counterfactual scenarios where minimum wages remain constant. We find that the ‘Gini coefficient’ increases by 16.08% in rural areas and 18.49% in urban areas, amounting to a 26% overall rise in wage inequality if minimum wages had remained at 1999 levels in 2018.

We also account for alternative mechanisms. For instance, states that raise minimum wages may also implement pro-poor policies like MNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) or strengthen minimum wage enforcement. We find that even after accounting for MNREGA implementation, the wage increases attributed to rising minimum wages persist. Second, although minimum wage enforcement could theoretically impact wage inequality, structural and administrative challenges in India limit its effectiveness (National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (NCEUS), 2007). While we find that enforcement, measured through labour inspections, increases the overall effect of minimum wages on the prevailing wages, there is no significant effect of enforcement on wage inequality.

Lastly, we evaluate the effect of minimum wage changes on monthly earnings inequality and employment. Our results for wage inequality are also mirrored in those for earnings inequality. This is driven by the fact that we do not find any reduction in the number of days that an individual reports to be employed when minimum wages increase. The null employment effects can potentially be explained by three factors – monopsony power in Indian labour markets (Muralidharan et al. 2023), if minimum wage changes are not large enough to have employment effects (or the own wage elasticity – that is, how much workers change their working days when wages change – is relatively small), and when employers pass the minimum wage increases to prices.

Concluding remarks

Existing evidence shows that the rise in minimum wages in developed countries decreases income inequality (for instance, see recent studies by Autor et al. (2016) and Bossler and Schank (2022)). However, relatively less is known about the impact of minimum wages on wage inequality in developing countries. Studies for China (Lin and Yun 2016), Brazil (Engbom and Moser 2022, Sotomayor 2021) and Mexico (Bosch and Manacorda 2010) find that a rise in minimum wages accounts for a decline in earnings inequality in these countries.

However, these economies differ from India in terms of compliance levels, informality of employment, and minimum wage setting. The level of informality in India, at 83%, exceeds that of Latin America (53%) and China (40-50%). Moreover, Latin America and China have higher compliance to minimum wages than other countries in South Asia (International Labour Organization, 2018).

Our results show that even in a setting characterised by extremely high levels of informality and low enforcement of minimum wages, a rise in these wages can lead to a decline in wage inequality. Specifically in the case of India, we find that rising minimum wages account for 26% of the overall decline in wage inequality during 1999-2018, with the largest impacts observed for the lowest wage quintiles. These gains are achieved without adverse effects on employment. These findings suggest that policymakers can effectively leverage minimum wage adjustments in India to reduce income disparities while preserving employment levels.

Saloni Khurana is a Digital and Labour Economist at the World Bank. Kanika Mahajan is an Associate Professor at Ashoka University. Kunal Sen is the Director of UNU-WIDER. Views are personal.

This article was first published by Ideas for India.

The need of the hour is to downsize the government bureaucracy. What Milei is doing in Argentina, DOGE is doing in USA, we need to do the same here in India.

The government with it’s bloated bureaucracy is a huge burden on the economy. There is absolutely no requirement for 53 ministries in the Union govt. Most of these ministries can be done away with and others merged together. That will rationalize personnel utilization and bring about greater efficiency and co-ordination.