A recent study noted that ‘the combined administrative and judicial functions vested in judicial officers, who are not trained or experienced in management principles, is the root cause for inefficiencies in court administration’. High Court judges across India are often made to head several committees. Do they really need to oversee matters concerning staff cars, furnishing, and buildings?

Judges often have to juggle various responsibilities in addition to carrying out their primary function of justice dispensation. While the need to entrust judges with the responsibility of being in charge of legal aid authorities is debatable, judges currently also carry out a host of administrative roles that would be best delegated to administrative personnel in order to free their time.

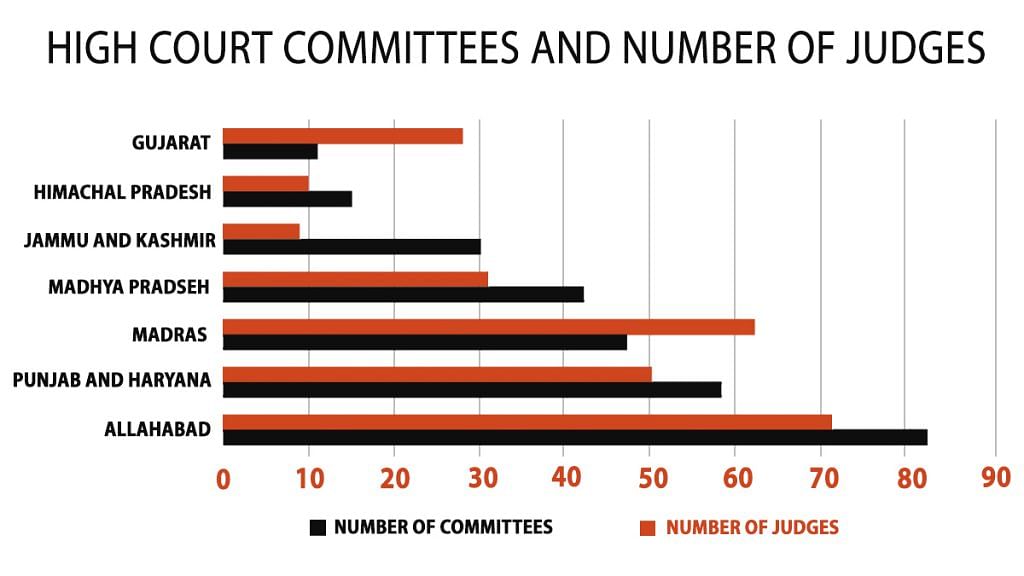

A look at publicly available information regarding the committees* set up in seven high courts (Allahabad, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Madhya Pradesh, Madras, and Punjab and Haryana) puts into perspective the amount of non-judicial duties that judges perform. Take a look at the number of committees in each of these high courts:

While a cursory glance at the number of committees and the number of judges in high courts could make one think that it can’t be too bad if each judge heads one committee, the crucial piece of the puzzle is understanding how many members there are in each committee. While some committees have just one high court judge per committee, most committees have at least three judges on them, and some committees have as many as nine.

The Allahabad High Court had approximately 80 committees and about 300 committee posts distributed across 70-odd judges.

In the High Court of Punjab and Haryana, 190 committee posts were allocated amongst 50 judges – the average number of posts per judge was close to four. However, what is concerning is the heavy concentration of these committee responsibilities on a few select judges in these courts, leading to even more worry regarding the amount of time these judges can then effectively allocate to their primary function of adjudication. Four of the judges in the High Court of Punjab and Haryana bore more administrative responsibilities than the rest with one judge holding 23 committee posts, another holding 16 committee posts, and two other judges being part of 13 committees each.

This trend was worse in the Allahabad High Court. Three judges were a part of more than 20 committees each – one judge was in 28 committees, one in 26 committees, and another in 22 committees. Add to this, some judges were given no committee at all.

Also read: Indian courts need MBAs and not Chief Justice to deal with pendency

Even if one were to argue that some of the committees may have been set up for a short term with a specific purpose, surely the work was significant enough that it warranted a committee to be set up and headed by a judge of a High Court. The task of holding positions in over 20 committees would not be a cause for worry if the work to be carried out by these committees were intrinsically linked to the adjudication of disputes. While there is a lack of information regarding the range of duties of each committee, overseeing functions that do not require the application of a judicial mind is a drain on precious time and manpower.

A separate administrative cadre should be established in the Indian judiciary to assist in administrative responsibilities and lessen the burden on judges. Judges divesting themselves of responsibilities such as overseeing improvements in court furnishings is something which should be a no-brainer. Hiring a dedicated group of administrative personnel at the high court, who possess the required managerial skills to carry out functions that do not require a legal mind, will go a long way in providing judges a few more additional hours to focus on being judges, their hard-earned job.

Also read: No more justice delayed: Jharkhand shows India how to deal with snail-paced judiciary

*Note: Information regarding committees, their members, and number of sitting judges are based on the following sources: Websites of the High Courts of Jammu and Kashmir, Madhya Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh (information as of 2019), annual reports of the High Courts of Gujarat and Madras (information as of 2018), Punjab and Haryana (as of 2017), and Allahabad (as of 2015).

The author is graduate of the National Law School of India University, Bangalore and works at DAKSH as a research associate. Views are personal.

So far Parliament has shied away from legislating to make judges accountable and stand up to judiciary for nullifying the laws passed by parliament under the pretext of judicial review. Keeping judiciary unaccountable is a sign of week parliament full of timid MPs..

Finally, one really useful article to educate the people from the PRINT. That is why, I keep insisting that you need not hire NRIs who live in other countries.