More has happened in the last 10 days to resolve the India-China confrontation in Eastern Ladakh, which began in April- May 2020, than in the preceding 4.5 years.

The most visible manifestation is the disengagement, confirmed by the Army, which began on 22 October in Depsang Plains and Charding La, south of Demchok—the last two of the six areas where the People’s Liberation Army had intruded to blockade India’s patrolling. A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson also tersely confirmed that “in accordance with the resolutions reached recently… the Chinese and Indian frontier troops are engaged in relevant work.” The disengagement was expected to be completed by 28-29 October and patrolling was set to resume by the end of the month.

For the last six months, India and China have engaged in hectic diplomatic exchanges, with speculation galore about a Modi-Xi meeting on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit at Kazan. Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri pulled a rabbit out of the hat on 21 October when he cryptically declared that an agreement has been reached on “patrolling arrangements”. On the same day, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar went a step further at the NDTV World Summit, stating: “We reached an agreement on patrolling, and we have gone back to the 2020 position.”

The following day at Kazan, Misri confirmed the Modi-Xi bilateral meeting and added, “regarding patrolling and grazing wherever applicable—the situation there will revert to what it was in 2020.” However, he clarified that these arrangements were specific to Depsang and Demchok and the status quo would prevail with respect to earlier agreements.

On 23 October 2024, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping held their first formal meeting in five years on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit. Both leaders welcomed the recent agreement on patrolling and disengagement. During their talks, Modi gave priority to the maintenance of peace and tranquillity on the borders over broader bilateral relations, while Xi emphasised the opposite. Both sides agreed that the Special Representatives mechanism must be utilised to ensure peace on the borders and work toward a fair, reasonable, and mutually acceptable settlement of the boundary question.

However, the terms and conditions of this border agreement are shrouded in opacity. There is a stark contrast between the euphoric official statements and “official leaks” that have flooded the Indian media and the two cryptic statements given by a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson on 22 October and 25 October, apart from its interpretation of the Modi-Xi bilateral.

Also Read: Indian Army’s first brush with the PLA was in 1951. The windfall was Chushul airfield

New disengagement & patrolling agreement

The disengagement and patrolling agreement signed at Corps Commander-level talks at 0430 hrs on 21 October is restricted to the Depsang Plains and Demchok. It does not affect earlier agreements on disengagement with buffer zones, signed from June 2020 to September 2022 in Galwan Valley, north and south of Pangong Tso, and in the Kugrang Valley between Patrolling Points (PP) 17-17A, and 15-16.

There are speculative media reports, based on “official leaks”, about the resumption of patrolling in existing buffer zones and a comprehensive agreement for de-induction and de-escalation to restore the status quo ante April 2020. In my view, this would be the agenda for talks between the Special Representatives and may take a long time.

Unlike earlier agreements, there will be no buffer zones in Depsang and Demchok. In Depsang Plains, a mutual buffer zone was not practical as it would deny both sides patrolling rights to nearly 650 square km of respective claims. Also, for India, this area is the vital foothold on the Aksai Chin plateau, where Indian forces were deployed pre-1962.

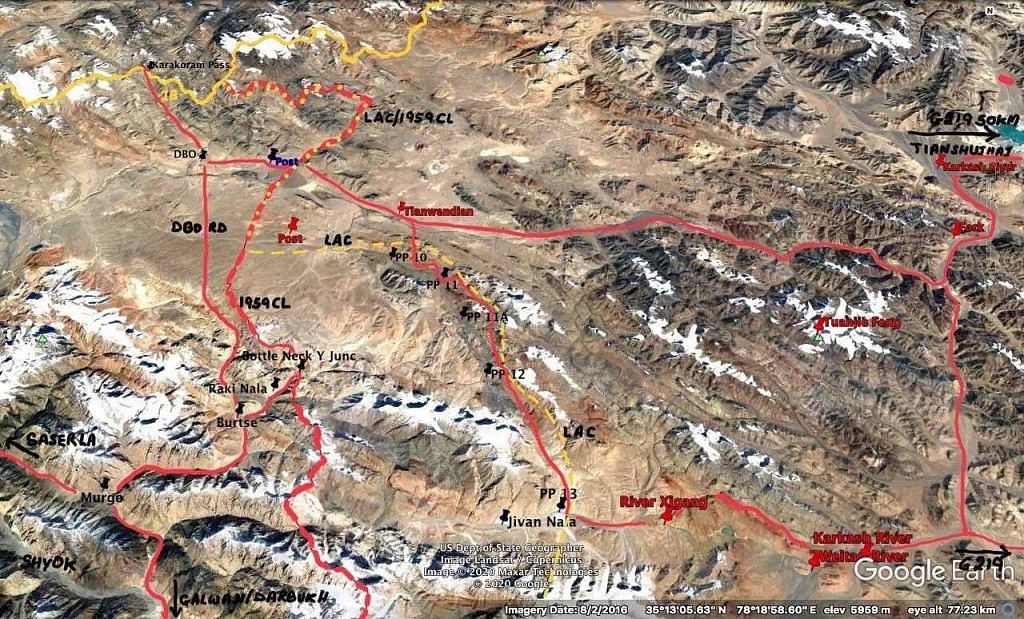

China’s 1959 Claim Line in Depsang Plains runs north to south from the Karakoram Range via Bottleneck/Y Junction, and further south to Jivan Nala. Prior to 1962, our posts were 5-10 km to the east of this line in the northern half of the plain, opposite the DBO airfield. In the southern half, these were 30-40 km east of Bottleneck. By 1993, the LAC coincided with the 1959 Claim Line in the northern half of the plains, but east of the Bottleneck, it was at 18-20 km. While we never physically occupied the southern half of the plains, the Indo-Tibetan Border Police, with a base at Burtse, patrolled up to Patrolling Points 10, 11, 11A, 12 and 13 until January 2020.

Due to the long distance between the longitude and latitude points shared by the Chinese during the 1960 India-China Official’s Negotiations, there is another variation of the 1959 Claim Line in the southern half of Depsang plains, which runs 3-4 km west of Bottleneck near Burtse and the Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) Road. Prior to April – May 2020, at times

With effect from May 2020, the PLA has blocked our patrols at Bottleneck, cutting off all routes to the PPs. The PLA patrols were also blocked from moving west of Bottleneck.

Under the agreement reached on 21 October, our patrols can now access the five PPs. The only controversial issue is whether the PLA patrols are restricted up to Bottleneck or allowed up to the variation of the 1959 Claim Line further west, closer to Burtse and DSDBO Road.

The intrusion at Demchok actually centres around Charding La, an imposing pass at a height of 5,600 meters on the LAC, 20 km south of Demchok. It gives visibility and access to a large tract of Chinese territory southeast of the LAC along the Indus River. It also provides a similar advantage to the PLA with respect to the Demchok area. Until May 2020 both sides patrolled up to Charding La, when the PLA denied our patrols access. Since both sides were keen to retain access to Charding La, a buffer zone was not practical and status quo ante has been restored.

In a nutshell, we have come as close as possible to the pre-May 2020 conditions in the Depsang Plains and Charding La, with the possibility of a variation allowing PLA patrolling 3-4 km west of the Bottleneck and closer to Burtse and DSDBO Road. In my view, in Depsang and Charding La, China has made a major concession to improve bilateral relations, after extracting the right to patrol up to two disputed areas in the northeast—one on Yangtse Ridge, 25 km northeast of Tawang, and the second at Asaphila in Subansiri Valley.

Also Read: Normalising India-China relations is an economic need. Modi is right to seek peace

The long game

As things stand today, China and India have completed disengagement at all standoff points. There are buffer zones varying in length from 3 km to 10 km along six points, but covering larger areas around the axis where no patrolling or deployment can be carried out. These buffer zones are in Galwan, PP 15-16, PP 17-17A, Finger 4 to 8 and Kailash Range. At Depsang and Charding La, status quo ante as of May 2020 has been restored—there are patrolling rights with minor variations, but no deployment can be carried out.

However, it is unlikely that status quo ante will ever be achieved with respect to the quantum of troops. Given the level of distrust, both sides will maintain enhanced deployments—if not in main defences then within striking distance for rapid mobilisation—for which adequate infrastructure has been created. India will likely maintain up to two divisions instead of one, while China will keep about six combined arms brigades. Reserves which were deployed for potential escalation and offensive are likely to revert to permanent locations with rights to conduct field exercises in summer. In fact, this has already happened.

It is now up to the Special Representatives, the Working Mechanism for Consultation & Coordination on India-China Border Affairs (WMCC), and military commanders to meet and work out the management of peace and stability on the borders. This includes plans for de-escalation, de-induction, and restoration of patrolling rights in the existing buffer zones.

In Eastern Ladakh, acceptance of the 1959 Claim Line will remain the basis of China’s stand in future negotiations. It has de facto reached it with or without buffer zones. The diplomatic challenge will be to replicate the Depsang and Charding La agreement in all buffer zones created earlier without making too many concessions, particularly along the McMahon Line.

Let there be no doubt, that any agreement reached will be tactical in nature to maintain peace and tranquillity on the border —it will not impact the overall boundary dispute and the competitive conflict for power between India and China in the international and Asian arenas.

Power flows from the barrel of a gun, and historically, the boundaries of nations have been shaped by the same logic. Since 1962, the quest for territory is not the driver of the border dispute; it is merely a tool for China to assert hegemony and enforce the pecking order.

Geopolitical factors drive the rapprochement between India and China.

However, conflict prevention is the most important one for India. China’s GDP is 4.7 times that of India’s, and its defence budget is three times larger. India needs time to bridge this huge differential and be in a position to challenge China. A realistic timeline for achieving this is 2047, when the Indian economy, going by the current 7 per cent growth rate, could reach $21 trillion. In the interim, any conflict with China could lead to embarrassing military setbacks and a drain on the economy.

Peace and tranquillity along the borders with China—as it prevailed from 1988 to 2013—will give India time to uplift its economy and carry out military transformation to become the third pole in the international arena by 2047.

Lt Gen H S Panag PVSM, AVSM (R) served in the Indian Army for 40 years. He was GOC in C Northern Command and Central Command. Post retirement, he was Member of Armed Forces Tribunal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Poor and socialist India won’t let go of socialism, so won’t be in a position to challenge China even after a 100 years. Territories have been lost to China for ever.