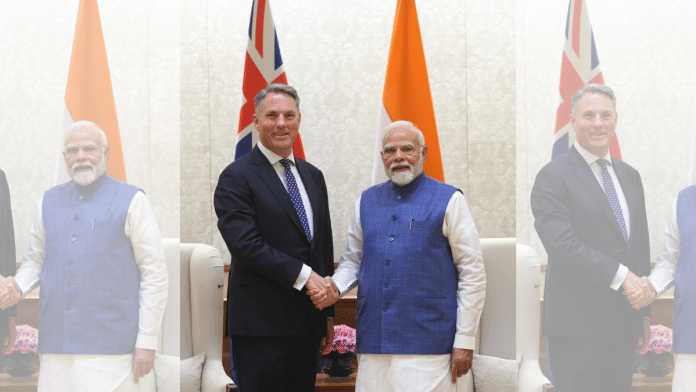

The recent visit of Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles to New Delhi has provided a significant boost to the burgeoning ties between India and Australia. This diplomatic outreach underscores Australia’s unwavering support for India in its battle against terrorism in all its manifestations. Notably, Marles’ visit comes shortly after the Albanese administration’s re-election, marking an early and decisive engagement with India at a time of heightened global uncertainty.

Reflecting on the trajectory of India-Australia relations, it is remarkable how far the partnership has come in a relatively short period. Just a decade ago, Australia was not a prominent feature in India’s strategic considerations. However, shifting geopolitical dynamics have brought the two nations closer. The year 2025 marks the fifth anniversary of the elevation of the bilateral ties from a strategic partnership to a comprehensive strategic partnership, placing Australia among a select group of countries with which India maintains a 360-degree engagement framework.

This enhanced partnership encompasses multiple overlapping mechanisms, including the 2+2 dialogue for high-level coordination on defence and foreign affairs, intergovernmental consultations, and a Free Trade Agreement. These initiatives reflect a shared commitment to deepening cooperation across various sectors, from security to trade and technology.

Critical drivers

At the heart of this evolving relationship lies a mutual recognition of the importance of defence and security collaboration. During Marles’ visit, both nations welcomed the signing of the Australia-India Joint Research Project and agreed to intensify and diversify defence industry collaboration. The upcoming third India-Australia 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue later this year is expected to further advance defence science and technology cooperation, enhancing interoperability and addressing common security challenges.

Beyond bilateral engagements, both countries are active participants in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), an informal grouping that includes the United States and Japan. The Quad aims to promote a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific, serving as a counterbalance to China’s growing influence. The inclusion of Australia in the Malabar naval exercises, alongside India, Japan, and the US, has further built interoperability and trust.

The Quad stands as the most prominent example of the plurilateral cooperation linking the United States and India with two of their closest strategic partners. Yet, America’s current relationship with India has lost the sheen it was expected to have. While Washington has not formally withdrawn from key security alliances like NATO or informal groupings such as the Quad, the Trump administration’s flippy-floppy foreign policy toward its allies and partners has irked all. Trump’s semi-betrayal of Europe on Ukraine has unsettled allies around the globe—including Australia and New Zealand, both formal defence partners of the US.

As the US-China rivalry develops, regional states are scrambling to protect their interests. There is little clarity on how Western powers might respond to a potential Chinese military takeover of Taiwan. A direct military confrontation between the US and China remains improbable, a reality acknowledged both overtly and implicitly by voices within and outside the US government. For Indo-Pacific nations caught in the geopolitical crossfire—reliant on China for trade and the US for security—investing in their own strategic resilience appears to be the most prudent path forward.

Also read: OTT is connecting India & Australia like never before—immigrants, racism, mental health

Beyond the Quad

Global military spending surged by 9.4 per cent in 2024—the steepest increase since the Cold War—driven by the return of attritional warfare and China’s growing maritime assertiveness. In Australia, this has reignited calls to overhaul defence capabilities. The urgency was echoed, albeit abrasively, by US Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, lamenting America’s “overgenerosity”. Yet, amid the unpredictability of leaders like Donald Trump and the transactional nature of US foreign policy, countries in the region are pursuing resilience.

And here, there are many more conversations that New Delhi and Canberra can have.

To refine the discourse around building resilience in the Indo-Pacific, a few critical questions must be addressed: How does the China factor shape India-Australia cooperation? How do these shared concerns influence their bilateral and multilateral responses? And finally, are there any missing links that, if bridged, could yield a more resilient and coordinated response to today’s complex geopolitical disruptions?

First, China’s strategic posture manifests differently for India and Australia. For India, the primary threat is terrestrial: a long, contested, approximately 3,488 km border remains a constant source of friction and a challenge to regional stability. Alongside this, India competes with China for leadership of the loosely termed “Global South”. While India holds substantial diplomatic clout and credibility, China leverages overwhelming financial muscle.

In contrast, the maritime domain is where New Delhi and Canberra find significant convergence. India faces encirclement through Beijing’s “string of pearls”—strategic investments in ports across the Indian Ocean. Similarly, Australia confronts Chinese influence through its growing presence in the South Pacific. Chinese capital has deeply penetrated this region, bringing Beijing uncomfortably close to Australia’s maritime borders.

In February 2025, this proximity turned provocative when a group of Chinese warships sailed into waters closer to Australia than ever before, marking a significant escalation and showing China’s blue-water naval capabilities.

This incursion triggered a heightened alert across Australia’s defence establishment. The Royal Australian Navy responded with immediate readiness measures—deploying vessels like HMAS Hobart for anti-submarine operations, equipped with an array of SAM missiles and advanced warfare systems. But it also highlighted a stark reality: Australia remains heavily reliant on the US for security, and its defence capacity falls short of China’s rapidly expanding military under Xi Jinping.

Understanding China, however, requires acknowledging its distinct conception of warfare. For the Chinese Communist Party, war ends with kinetic battles, but doesn’t begin there. Warfare is a continuum that begins with psychological manipulation, elite capture, and economic lure and coercion. This strategic ambiguity—combining symbolic aggression with soft power incentives—has allowed China to build relationships across the world, including Australia’s “near abroad.” From security agreements with the Solomon Islands and Samoa to expanding influence in Tonga, Fiji, and the Cook Islands, China has entrenched itself in regions historically viewed as within Australia’s strategic domain.

India, too, is familiar with these tactics—both on its borders and in the Indian Ocean. While Australia has evolved from the sinophilic era of Kevin Rudd to a more assertive and clear-eyed view of Chinese ambitions, the need now is to go beyond reactive defence postures.

Second, responses from both countries fall into two categories: individual capability-building, such as Australia’s increased defence spending and aspiring for niche tech under the AUKUS submarine deal—and other second-plurilateral frameworks with like-minded partners.

However, a deeper concern looms. While most strategic conversations focus on the possibility of a Chinese military move on Taiwan—and by extension, potential flashpoints involving Japan’s disputed Senkaku Islands—it is the immediate and ongoing threat that is more insidious: hybrid warfare.

Cyberattacks, disinformation, AI misuse, and critical infrastructure sabotage represent the grey zone where China operates most effectively. A recent Lowy Institute survey revealed that Australians rank cyberattacks as their top national security concern—above the direct US-China military conflict.

Way forward

Herein lies the opportunity: Australia could serve as a bridge between European institutional expertise and Indo-Pacific realities. The EU’s Enhancing Security in and with Asia (ESIWA) initiative recently established the Hybrid Intelligence and Policy Analysis (HIPPA) unit in Australia. For the first time, the EU has extended the capabilities of its Hybrid Centre of Excellence—based in Finland—into the Indo-Pacific, alluding to a convergence of security theatres.

India, with its active engagement in cyber and maritime security partnerships with the EU as well as with Australia and Japan, is well-placed to integrate into this framework. By linking disjointed initiatives and standardising hybrid threat responses, this cooperation could form the basis of a new and highly functional Quad—comprising the EU, India, Australia, and Japan—complementing the other Quad as and when the American worldview stabilises.

With participation from ASEAN and South Pacific partners, the new grouping could offer collective, institutionalised responses to hybrid threats—addressing the most imminent threats today, not simply preparing for a war in the future.

Swasti Rao is a consulting editor at ThePrint and a foreign policy expert. She tweets @swasrao. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

NZ has no formal defence relationship with the USA. It seems a shame India isn’t putting much more effort into strengthening its relations with the countries of South Asia and also with Southeast and East Asia as security & trade complement each other. It was disappointing to many of us outside India that India withdrew from RCEP, the world’s largest trade bloc which accounts for 30% of the world’s population (2.2 billion people) and 30% of global GDP.

Quad without the United States is a bit of a stretch. Europe does not share America’s concerns as far as China is concerned. Would be happy to continue trade and investment linkages absent US pressure. Australia’s own economy is such a good fit with China’s. It has paid a price by raising the pitch, most recently with AUKUS. Concerns in Australia about both the cost and utility of AUKUS. Instead of meandering all over the Asia – Pacific, creating artificial constructs, better for India to focus on the land threat from China. Have a productive conversation about the way forward.