Bal Thackeray was India’s only purely parochial leader. He was also his own brand manager and a man deeply in love with himself.

Was Balasaheb Thackeray a mass leader or a mafioso? The truth is, you will find his followers and detractors only describe him in extremes. But both will agree on one thing, that he was one of a kind, an original.

I learnt how much of an original he was when, in a ‘National Interest’ article more than a decade ago, I described him and his party as mafiosi. My phone rang late that Saturday evening as I sat with my family at dinner in Baan Thai restaurant (shut down in 2005) in the basement of New Delhi’s Oberoi. It was a call from Balasaheb in Mumbai. I went out looking for better signal and braced myself for a diatribe.

But he was dripping charm. “Of all the people who abuse me, Shekharji, you write most delightfully,” said Balasaheb.

“Thank you, Balasaheb,” I said, relieved. “So what are you doing for me for abusing you so delightfully?”

He offered me dinner the following Thursday at Matoshree, suggested I bring along my wife and asked if we were vegetarian or teetotallers. And when he was told we were neither, he warmed up again.

“Aap Gupta ho kar bhi yeh sab kuchch kartey hain?” he asked.

“Jab aap Thackeray ho kar itna kuchch kar sakte hain…” I said.

We resumed that conversation at his home the following Thursday, Uddhav and his wife Rashmi in attendance and their still small children playing in the family living room. Also present was a party MP and loyalist, B.K. Desai, whose only contribution was to nod furiously in affirmation whenever Balasaheb spoke. Much of the conversation was on expected lines. Until we asked, pointing at his framed picture with Michael Jackson, what he thought of him. And if he also thought skin was peeling off from his face.

“That I don’t know,” he said. But his eyes lit up as he told us his favourite MJ story.

Jackson, he said, was accompanied by “a lady and several children, and one of them asked where the toilet was”, said Balasaheb, pointing to the toilet door next to their living room. Then, according to him, one after the other, all the children went in. “MJ and the lady joined them,” he said. “Uske baad, they bolted the door from inside and did not come out for half an hour”, he said, and asked in what looked like genuine amazement, “so what do you think they were doing together inside?”

Everybody sniggered. What was this fascination with rock and film stars and beauty queens, why do all of India’s Miss Worlds have to visit him? “My daughters-in-law are more beautiful than any Miss Worlds,” he said, dismissive of any suggestion of starry-eyedness on his part. But the fact is, his fixation with the glamour world was real and deeply political. He interfered, more by strategic, political design than compulsion of habit, in cricket and cinema. Stars, including many Muslims, had to come to him for endorsement and, in a barely camouflaged manner, protection.

If Mumbai was the capital of Indian popular culture, from cinema to cricket, fashion to television, Balasaheb understood first, and better than any of his rivals, its value as a political force multiplier. Each time he threatened to ban a film, a star or a cricket match, or whenever a star of some kind visited him, he was guaranteed two things: instant headlines, and a perception of power overriding all legal and constitutional authorities. If an MJ concert could only be held with his approval, MJ had no choice but to visit his home, drawing an armada of OB vans. And if his munimjis then nudged the organisers of any such event for a little consideration, would anybody dare to say no? And would anybody dare to call this extortion, or Balasaheb a mafioso?

He used the pusillanimity of both, Congress governments as well as the showbiz, to build this image of the real ruler of Mumbai, though never elected. The framed picture with MJ, displayed right behind his tiger-skin throne, was his most valuable trophy, and told you that the richest, most famous stars of the world had to salaam him to perform in Mumbai. Such was his power over his party, and so mercurial his ideology, that he could demand summary death sentences for all the 1993 serial blasts’ accused, while at the same time pleading the cause of Sanjay Dutt, a half Muslim.

He did it not so much because he thought Sanjay was innocent, or his father, Sunil, his friend. He did it precisely because both were famous, and Sunil a prominent Congressman already. If a powerful and popular Congressman from the city, in fact a Central minister, had to come and seek mercy for his star son from you, it again guaranteed both publicity, and a notion of unparalleled clout. People can call you a don, a mafioso or sarkar, as portrayed by Senior Bachchan in Ram Gopal Varma’s 2005 film of the same name, but it is power you can monetise, for votes, cash, or both. In fact, even for sympathy and grief. Remember how sad and grief-stricken Bollywood stars looked at his funeral. They knew Balasaheb’s offspring would perpetuate his dynasty. So why not perform once again for the cameras? Faking it is their avocation, after all.

Just as he mastered the use of popular culture as a key for his control of Mumbai, he also understood the power of the media, particularly in a mostly literate city. He built his party — and dynasty — newspaper Saamana and spoke through its editorials. Saamana was his party organ much more than even Ganashakti has been for the CPI(M) in Bengal. He probably picked up the idea of a Dussehra address at Shivaji Park — almost the only time he spoke in public — from the RSS sarsanghchalak whom he routinely overshadowed in the headlines the next morning. He was his own media manager and manipulator. He employed a combination of intimidation and charm, but did that sort of differentially. The goons routinely ransacked Marathi media offices and editors’ homes while he poured his enormous personal charm on English journalists. He would have admonished me for being so ungracious, if not ungrateful, for saying this, but that dinner invitation was probably evidence of this cynical, differential strategy of media “management”. He has been called many things, and most often, a bundle of contradictions. But the description that fit his politics most of all was “cynical”.

You would wonder sometimes if he really hated the non-Marathis, the Christians, the Muslims, even the Pakistanis, as much as he pretended to. He would threaten to burn Mumbai if Pakistan played cricket there and then be all shreekhand and honey when Javed Miandad came calling. Either way, he got the headlines and reaffirmed his power. Probably a fairer description would be, he used all his avowed hatreds and antagonisms as elements of his own brand-building.

In marketing terms, he was his own brand manager. In human terms, we can never be sure he really hated all the people he cursed and abused. You can be sure of only one thing: like his film contemporary Dev Anand, he was a man deeply in love with himself.

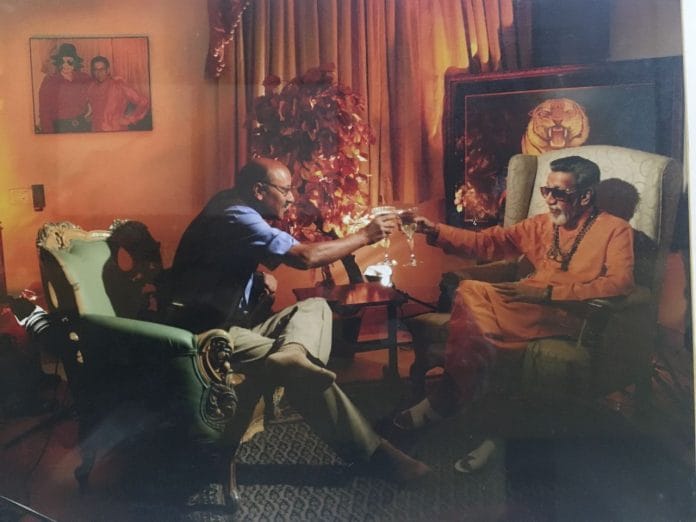

I renewed my acquaintance with Balasaheb several years after that dinner. Or rather, he did. Uddhav called me, in January 2007, to say that Balasaheb was turning 80, and would like to give me a freewheeling interview, but wouldn’t walk. Balasaheb took personal care to get the setting right. The tiger in the back, two glasses of white wine and the bottle too, all the props were there. As Uddhav had promised, he ducked no question, including on his (then) recently estranged nephew Raj. “What was the difference between him and Uddhav,” he asked resignedly. “He used to play in my lap, peeing and wetting me all the time. But if I have to choose one, then one is son and the other nephew.” It was the only time he had shown some genuine emotion.

He was back to normal when we spoke of “painter” Hitler, “lazy poet” Vajpayee, Muslims, Pakistanis and so on. And corruption? I asked why he had Suresh Prabhu fired when he was so competent and honest.

“You say he was honest?” he asked. And then went on to recount a conversation with Pramod Mahajan on Prabhu refusing to make any “contribution”, claiming he was making no money as power or environment minister.

“Pramod told me,” he said, “that if anybody in the cabinet (NDA’s) claims he is not able to make any money, he was either a liar or a moron.” So why, he said, “should I have a thief or a moron as a Central minister”. This, by the way, was entirely on the record. Now don’t ask me why I call cynicism the hallmark of his politics.

“Are you a mafioso?” I asked again.

“I know you wrote this earlier too. But tell me something. If I was indeed a mafioso, you think you would have DARED (emphasis his) to come and speak like this?” he said.

Style and strategies apart, there was one more thing that set Balasaheb apart from the political class in India. Even in a political pantheon filled with regional and ethnic leaders, he was the only one to be purely parochial. At a time when the Akalis were getting more Hindu MLAs elected than their partner BJP in Punjab and the BJP got more Catholics elected than the Congress in Goa, he continued with his Marathi (Hindu) Manoos formulation. Anything else, he knew, with the cynical single-mindedness of a brand manager, would confuse his “customers”.

Postscript: Yet, it seems, at least once, he claims to have been foxed and that too by a poet-journalist. At that dinner, grandson Aditya was prancing around in one of those WWF (show wrestling, not wildlife) tees with the picture of a shaven-headed wrestler, I think famous as Papa Shango.

“Yeh kya, idiot Pritish Nandy ka shirt pahan ke ghoom raha hai,” he said.

“He is your party MP,” I said. “How can you speak of him disparagingly?” I asked, genuinely confused.

“Theek hai. Idiot toh main hoon, not Pritish. He took Rajya Sabha from me and I figured only much later, too late, that he is Christian.”

This article was first published on 24 Nov 2012.

Why this obsession with people like Balasaheb? Some self-styled pundits on mysoginy would say,that some women want to be abused! Sekharji can’t call a spade a spade? Everything is not black or white; agreed, but there is black and there is white. Painting all on some shade of grey is….well, I like Sekharji and so would spare him.

How many politicians can now say – idiot tho mein hoon- now?

Just for that should agree that he was an original.

There you go again.

‘I’ covered kanshi ram ages back.

‘I’ said this to Balasaheb.

Narcissism of the worst kind Mr Gupta. Whatever happened to real journalism.

People deserve their politicians/leaders