Despite achieving rapid economic growth over the last few decades, India is home to one third of all malnourished children in the world. The latest rankings of the Global Hunger Index yet again reveal how India lags behind its poorer neighbours, including Pakistan and Bangladesh, on multiple child nutrition indicators. India has been ranked 101 out of 116 countries on the index. Malnourishment in early childhood has long-lasting negative impact on health and education. It also has economic implications for both, the children affected and their communities. Therefore, India urgently needs solutions for eliminating child malnourishment.

Our recent research suggests that feeding young Indian children more animal-sourced and vitamin A-rich food would help reduce their malnutrition rates. Livestock ownership and participation in the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme could be instrumental in encouraging such dietary changes.

Recent rise in child malnourishment

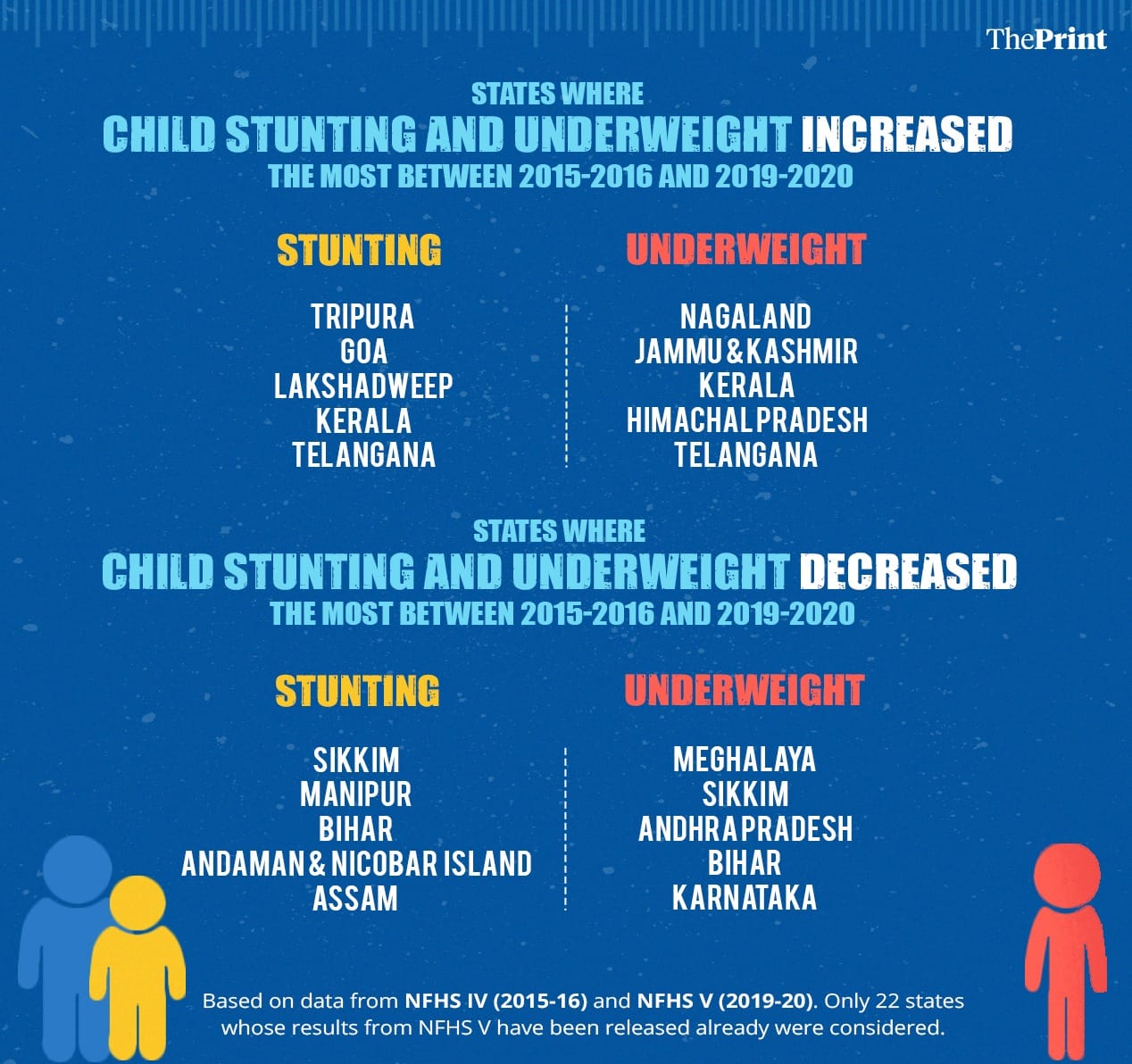

After witnessing reduction in child malnourishment in the last twenty years, the trend in India seems to be reversing. Data from the latest round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 2019-20) released for 22 Indian states indicate that in the past five years, more than half of the states experienced an increase in child stunting (children too short for age) and more than two third increase in child underweight (children too thin for age). The table below shows which of the 22 Indian states have been most successful and which least in tackling child stunting and underweight. In the last two years, Indian children’s nutrition outcomes have been further negatively affected by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

Also read: In Covid year, UP dispatched 3 midday meal rations, but some students are still waiting

Infant feeding and nutrition outcomes

The World Health Organization (WHO) advises that children should be exclusively breastfed until six months of age and after that receive alongside milk solid, semisolid or mushy food of sufficient variety. Research has previously shown that ‘weaning’ children (in other words, starting them on solids) timely at six months is important for good nutrition outcomes. Diverse diet in early age has also been found to have a positive effect on children’s nutrition status. But many Indian families do not follow these two practices when feeding their young children. Around 23 per cent of Indian children between six months and two years are not weaned at all, and 80 per cent do not consume a diet sufficiently diverse, according to the WHO. Feeding all children from six months of age a varied diet would therefore certainly help lower their malnutrition rates.

Also read: Why Modi govt wants to distribute fortified rice & how it will help combat ‘hidden hunger’

Importance of animal-sourced food

In addition, all complementary food is not equally beneficial for children. Our study examines the relationship between specific types of weaning foods and nutrition outcomes and finds that feeding children fruits and vegetables rich in vitamin A (such as carrots, tomatoes, spinach, and mangoes) and animal-sourced foods (fish and meat, eggs, and dairy products) has a particularly positive effect. Feeding children any animal-sourced food is linked with an 11 per cent reduction in stunting while feeding them both meat and dairy with a 16 per cent reduction in underweight. Unfortunately, the consumption of animal-sourced foods is low among Indian toddlers. In the NFHS 2015-2016 sample of more than 50,000 children aged between six months and two years, only 28 per cent children ate any dairy products, 14 per cent any eggs, and 10 per cent any meat or fish the day before the survey.

Also read: How this remote, backward UP district is fighting malnutrition amid Covid pandemic

Encouraging better nutrition practices

Our study further analyses if owning cattle and poultry, or participating in ICDS has any impact on children’s diets and nutrition.

We find that owning poultry, unlike owning cattle, encourages good child feeding practices. This is most evident at the village level. In villages where many families own chicken, toddlers are on average five times more likely to eat meat and have 20 per cent to 30 per cent lower rates of stunting than toddlers in villages with low chicken ownership. Poultry ownership is prevalent particularly in North-Eastern India (Meghalaya, Sikkim, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh etc.) while relatively uncommon in northern states such as Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. Families that raise their own chicken naturally have easier access to both eggs and poultry meat. But it is also likely that in villages with higher poultry ownership, eating animal-sourced food is generally more common and accepted than in villages with low poultry ownership.

We also find that children who participate in the ICDS eat more fruits, vegetables, and animal-sourced food than non-participating children. However, the better feeding practices are not reflected by significantly better nutrition outcomes.

Also read: Caste discrimination – an overlooked factor in Indian kids’ stunted growth

Remedies

It is clear from our study that wealthier households in India can afford to feed their children better food than poorer households. But interestingly, we find that most of the inappropriate practice in child-feeding cuts across socio-economic lines, with 75 per cent of even the wealthiest households in the country not feeding their toddlers a sufficiently diverse diet. Greater recognition of the importance of starting children on solids on time, with diverse diets that include fruits, vegetables, and animal-sourced food, would thus definitely aid in reducing their malnutrition rates.

High child malnutrition rates in India are caused by a multitude of factors. A key one, as our research shows, is the scarcity of fruits, vegetables, particularly animal-sourced foods in young children’s complementary diets. Better parental and public awareness of appropriate complementary feeding practices, raised through the dense national network of ICDS anganwadi centres as well as through other nutrition policies and programmes, could help address the problem of Indian child malnourishment

Dr. Ivica Petrikova (@IvicaPetricova) is Assistant Professor, Department of Politics & IR, Royal Holloway University of London. Arvind Kumar (@arvind_kumar__), PhD Scholar, Department of Politics & IR, Royal Holloway University of London. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)