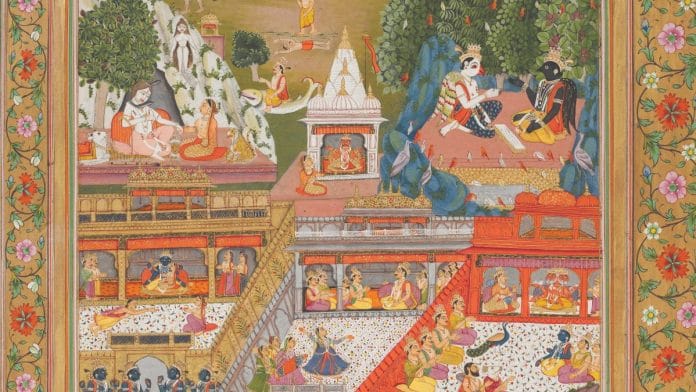

Every one of its over 1,000 pages shines with gold leaf and Awadhi calligraphy. It is painted with vast cityscapes, crowded courts bedecked in textiles. In it, Ram is drawn by hands Hindu and Muslim, in the styles of a dozen workshops from Bengal to Rajasthan. This is the story of one of the last great flowerings of North India’s courtly arts, a world of Sanskrit and Persian, of Brahmin scholars and Muslim weavers, of coffee houses and European fashions. A world that is almost lost to us today—which produced, perhaps, the most glorious visual Ramayana ever made.

Benaras’ financial boom

In the late 1700s, North India was changing, and nobody knew what the future held. A few decades prior, Nadir Shah, a shepherd-turned-emperor of Iran, had sacked Delhi, massacring over 30,000 of its inhabitants. The Mughal empire was a shadow of itself, and power had passed into the hands of many regional kingdoms: Awadh, Hyderabad, the Sikhs, and the Marathas. Worryingly, the British had taken over Bengal—once the richest region in all of North India. They had already humbled Awadh, and were moving to seize much, much more.

Driven by all this turbulence, North India’s economy and urban constellations were changing. As historian CA Bayly writes in Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars, at the height of Mughal power in 1700, the largest commercial centres had been Agra, Delhi, and Lahore. By 1800, they were rivalled by centres in the Gangetic Plains: Lucknow and Benares (present-day Varanasi). Though today it’s well known as a pilgrimage centre, Benares in the 1700s was also a city of financial opportunity. You’d see the strangest, most unexpected relationships in Benares. Lingayat pilgrims from Karnataka, for example, settled in the Madanpura area and became moneylenders to the area’s Muslim weavers.

The city’s rulers were the Narayan dynasty, a clan of landowning Bhumihar Brahmins. They were vassals of the British, with no say in military affairs or foreign policy. Like many other royals of the time, the Narayans turned to cultural and religious matters to keep themselves busy. The courtly culture of the Mughals was quickly disappearing, and new European ideas were arriving.

At the same time, Benares had a rich (if exclusive) Sanskritic culture focused on the god Shiva. This coexisted with boisterous popular worship of Ram, exemplified by the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas, which was sung in Awadhi, a dialect of Hindi. On top of it all, Benares was also a centre for the followers of Kabir, a devotional poet who criticised both Hindu and Muslim practices.

As you can imagine, such an eclectic society produced an equally eclectic work of art: the Kanchana Chitra Ramayana.

Also read:

The last bloom of North Indian art

The popularity of Ram, the ideal god-king, rises in times of political churn in India. The 1700s were no exception. Though Benares was most holy to Shiva, the ruling Narayan dynasty were great devotees of Ram. The Ramcharitmanas was, to them, the ideal text: it depicted Shiva as a devotee of Ram, and Ram as a devotee of Shiva reconciling Benares’ two most powerful religious strands. Patronising the Ramcharitmanas was guaranteed to bring popular acclaim.

When the Ramcharitmanas was first composed in the 1500s, the idea of telling Ram’s story in the vernacular was not popular at all. Tulsidas, its creator, was snubbed by the city’s conservative Shaivite Brahmins. In her introduction to Book of Gold: The Kanchana Chitra Ramayana of Banaras, the late art historian Kavita Singh quotes one of his verses: “Some call me a fool, some call me a sage, some call me a [high-caste] Rajput, some a [low-caste] weaver… I don’t need to ruin anyone’s status by associating with them. Everyone knows I am the slave of Ram… if I need to, I’ll beg for my food and sleep in a mosque.” The booming Benares of the 1700s, home to many Vaishnavite ascetics, instead welcomed the Ramcharitmanas with open arms. Unlike Valmiki’s Ramayana, its Awadhi language made it instantly accessible to all the city’s castes and people.

And so, the Narayan court hosted Ramcharitmanas scholars and developed a lavish Ramlila performance that lasted for weeks at a time. (It continues in Benares to this day). Completely sidelined by the British, the Narayans reached out to all their contemporaries, inviting artists to create the first-ever fully illustrated Ramcharitmanas. Artists came from Delhi, which, in its imperial twilight, had become home to coffee houses, provocative Urdu literature, and Mughal-obsessed British White sahibs. They came from Lucknow, where the Nawabs of Awadh presided over a court of music and dance and European fashions. They came from Kota and Jaipur in Rajasthan, dazzling with colourful textiles and avant-garde artists. Some were drawn by family and professional networks. Others, as Singh notes, may have been sent by nawabs and rajas in a show of diplomatic solidarity.

The Kanchana Chitra Ramayana was to have nearly 1,100 pages, of which 548 were illustrated. Each illustration took months to finish. It needed the attention of master sketchers and outliners, apprentice painters, and expert illuminators to create its gilded borders and golden palaces. It needed a constant supply of precious materials to turn into paint and pigment. Its workers needed food, residences, and cash. Most importantly, it needed project managers to assign pages to specific workshops, to put artists in touch with religious teachers who could explain complex philosophical ideas, and to manage calligraphers and illuminators for each page.

The pages of the Kanchana Chitra Ramayana are startling to look at, because of the sheer variety of regional and individual styles on display. The delicate, exquisite empathy of the Mughal courtly artist; the heavy-lidded eyes of the Jaipuri; the architecture-focused composition of the Awadhi.

It took 18 years, 1796–1814. This, oddly enough, corresponds almost exactly to the career of Napoleon Bonaparte and the French Revolution. While Europe’s bureaucratic attentions were directed to mass slaughter and colonising the world, North India’s courts, increasingly sidelined, produced the magnificent Golden Picture Ramayana. It froze in its art a dazzling, diverse regional world—one that seems increasingly distant today.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)