Holi is one of India’s most popular and distinctive festivals. But how did the idea of throwing colours in the springtime develop? It took over two thousand years for Holi to take on its recognisable form; over this time it developed from a festival focused on women and erotic love, to a celebration of cosmic deities, sponsored by states.

In many ways, this festival expresses not only the fun and renewal of springtime, but also India’s ideas of gender relations, and the politics of the powerful—as regressive statements by certain UP politicians show.

Holi and the spring

What is Holi, really? Today, this spring festival is best defined by two practices. First, the bonfire celebrating the destruction of the demoness Holika, followed the next day by the throwing of coloured water and powders, amid general merriment. Holika, it’s believed, was a demoness who attempted to kill her nephew Prahalada, a devotee of Vishnu. In North India especially, the throwing of colours is also linked to Krishna, one of Vishnu’s avatars. All of these – the bonfire, the colours, the connection to Vishnu – evolved separately, before their amalgamation into Holi.

Interestingly, a spring celebration by the name of “Holi” is perhaps the oldest surviving festival of the entire Sanskritic corpus — older even than Dipotsava/Dipavali festivals of lamps. A “Holaka” spring festival is mentioned in the addenda to the Atharva Veda, dating to about the 7th-8th centuries BCE, but there’s no mention, at this early date, of demoness-burning or coloured powders. In the centuries thereafter, seasonal festivals continued to develop, and, as historian Sam Dalrymple writes, there are also occasional mentions of “festivals of colours”. But we don’t have a clear sense of Holi as it’s imagined today.

Something changed in the first millennium CE, though. As I’ve discussed elsewhere in Thinking Medieval, this was a time of extraordinary innovation, stimulated by Central Asian rulers such as the Kushans and the trade networks they brought with them. Sanskrit broke out of priestly circles and into courtly literature. Suddenly — like the springtime itself — there is a great blossoming of spring festivals in the sources, from Kashmir to the Deccan. Historian Leona Anderson, in “The Indian Spring Festival (Vasantotsava): One or Many?” analyses this. The names and celebrations are many: Vasantotsava, Phalgunotsava, Chaitrotsava, Madhutsava, Kamotsava, Madana-Mahotsava. There is a surprising common thread: they were all centred around a god who is no longer important in Hinduism. Kama, the deity of erotic love.

Festival of Kama

In the rich, confident, urban milieu of courtly Sanskrit, descriptions of spring festivals are everywhere. Around the 7th century CE, the poet (and possibly emperor) Harsha has this to say in his epic, Ratnavali.

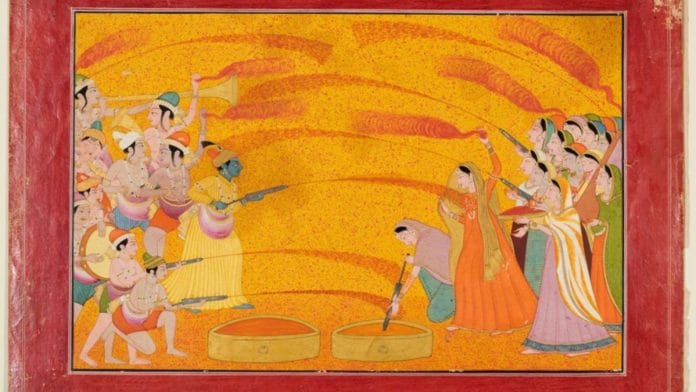

“Observe the charm of this, Kama’s festival… with citizens dancing at the touch of water from syringes. Citizens are voluntarily seized by lovely women under the exhilaration of wine… all the quarters are rendered yellowish-red with a mass of fragrant powder scattered all about… Behold the sporting of courtesans who are charming on account of their hissing uttered when struck by water from syringes charged by naughty gallants.” (Translation by Anderson, Vasantotsava: The Spring Festivals of India, Texts & Traditions.)

This, and other verses, tell us why Kama’s festival was so popular: normal social boundaries were blurred, with men and women publicly consuming intoxicants together. All castes and professions took part in the merriment. Women played a major part in the general rowdiness: they would roll about in flowers, ingest mango-blossom wine, and tease the men. While the gender roles have reversed in India today, some of this survives in traditions such as Lathmar Holi, where women thrash men (playfully) with sticks.

Medieval women would clamber onto swings in gardens; they would also lead the worship of Kama, whose idols were placed at the foot of flowering trees. Kama was believed to have been born in the springtime, thus linking the blossoming of the world to the blossoming of desire, to the fertility of women. Premodern Indians were not coy about sex and eroticism. The worship of Kama, the centrality of women to the spring festivities, and the dissolution of societal norms were all part of the seasonal cycles of the world. Indeed, Dr Anderson suggests that the throwing of colours may have developed from the throwing of flowers and pollen; the squirting of water from syringes may also have had erotic undertones. In fact, there are rather explicit verses, across the length and breadth of courtly Sanskrit, describing coloured water and pastes caressing various body parts.

But despite the prominence of Kama festivals in literary Sanskrit, he doesn’t have independent myths of his own in the religiously-inclined texts, such as the Puranas. Indeed, the Puranas are much more interested in the burning of Kama by the cosmic deity Shiva, seeing his springtime rebirth as a result of Shiva’s grace. It’s possible that Brahmin commentators were not as enamoured of the god as the general public was, and sought to incorporate him into their own myths. This brings us to the next step in the evolution of Holi.

Also read: Yoga and Kama are not said in same breath in India today. But it should

The royal Gods

As we’ve seen, the spring festival was linked with colour and celebrations fairly early in its history. What, then, of the burning of Holika?

Around the 11th century, Anderson writes, some Sanskrit manuals take note of “Holaka” as a ritual performed in the East. Other medieval texts, such as the Bhavishya Purana, describe a demoness, Dhaunda/Holaka, a malevolent figure who kills children. Therefore, says the Purana, a Holaka festival must be performed to burn her. She seems to have been a terrifying local deity, not specifically associated with Prahalada or Vishnu.

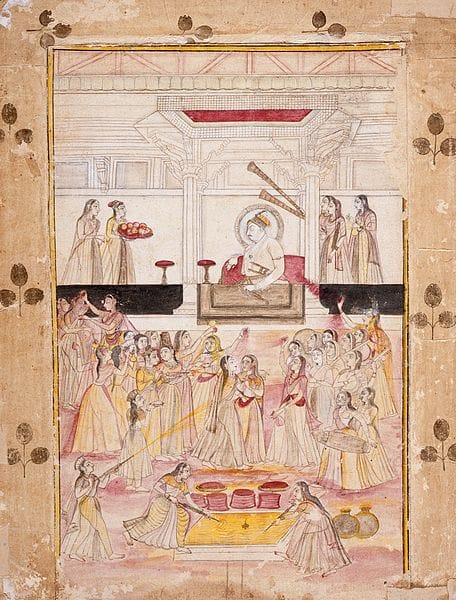

Meanwhile, the courtly celebration of spring continued to develop, though the popularity of Kama had substantially declined. By this time, women had gone from the protagonists of the spring festival to side characters for the king’s enjoyment. The finest imported powders — sandalwood, musk — were used by royals to celebrate the spring; the syringes were made of gold and silver, shaped like the horns of wild bulls. Balls of flowers and perfumed silk were tossed in the games; fountains shaped like elephants and lions poured perfumed water into which royals splashed.

The final step in Holi’s evolution, which brought together all the separate strands and finally got rid of poor Kama, was taken in the 15th-16th centuries. A wave of Central Asian conquests sparked off new states across the subcontinent. Lacking a sectarian link, Holi could easily be reinvented; as historian Rana Safvi writes, Mughal writers called it Eid-e-Gulaabi or Aab-e-Pashi; paintings depict various Muslim rulers, from the Deccan to North India, playing with women, colours and flowers just as their Hindu predecessors had. Indian Muslims were uninterested in the festival’s Kama links — a view shared even by new Hindu states such as Vijayanagara.

Indeed, as Dr Anderson writes, Vijayanagara texts such as the Virupaksha-Vasantotsava-Champu completely reinvented the spring festival as a chariot procession, where the state god, Shiva Virupaksha, was brought out to be worshipped by crowds of pilgrims. Other texts, such as the Mohana-Tarangini, Chenna-Basava-Purana, and Jaimini-Bharata briefly mention the worship of the god Vasanta (Spring, not Kama), and describe water sports where teams of royal ladies would compete to spray each other for the king’s enjoyment. By this time, syringes were gem-studded, shaped like birds, elephants, horses, and deer; we also hear of spectacular multi-coloured pools, green, red, blue and yellow, in which swans and fish swam. There is a common theme in spring celebrations from this time: whether Hindu or Muslim, women were no longer the protagonists of the festival, nor were they as public as they had once been.

Similarly, around the same time, the ‘eastern’ tradition of Holika burning moved deeper into the Gangetic Plains. Gaudiya Vaishnavism, from Bengal, took root in Mughal-ruled Vrindavan, attracting patronage from elite Rajputs. Now it was the turn of Vaishnavism to absorb the spring celebration. As Anderson shows, in the 16th century, Krishna supplanted Kama in texts like the Hari-Bhakti-Vilasa. Over the next centuries, as the worship of Vishnu’s avatars again became central to North Indian states, the burning of Holika was linked to Prahalada, Vishnu’s devotee; the throwing of colours was connected to Krishna’s games with cowherd-girls. And so Holi, as we know it, was born and reborn, like the spring in the endless cycle of seasons.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire’, and the award-winning ‘Lords of the Deccan’. He hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti and is on Instagram @anirbuddha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)