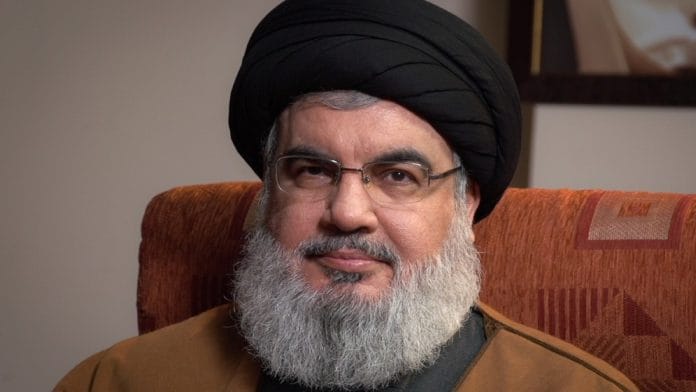

Long after his teenage son was killed, fighting Israeli troops in the hills of southern Lebanon’s Jabal al-Rafi, the man who appeared in a black turban to urge more young men to join the ranks of the martyrs revealed he cried in private: “I wanted to get a tissue paper to wipe my sweat at least from my eyeglasses,” Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah recounted. “But I thought these television stations reporting the event might be selling their film to Israel and people will assume I was wiping tears.” “I preferred not to give the enemy an image of a grieving father.”

The killing of Israel’s most dangerous adversary in an airstrike on Friday—which levelled six buildings in the heart of Beirut—has made clear that Tel Aviv has the intelligence and military capabilities to bring its Iran-backed regional enemies to their knees.

Facing ferocious Israeli assault, the terrorist group many experts believe is the most heavily armed non-state military in the world, has flailed. Earlier this month, the country’s intelligence service, Mossad, set off thousands of explosives-laden pagers in an operation which crippled Hezbollah’s leadership. And Israel’s airstrikes and missile defences have ruthlessly exposed the limitations of Hezbollah’s much-hyped missile and drone arsenal. Top Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh and Mohammed Deif, together with Hezbollah’s Fuad Shukr, have also been killed in recent weeks.

The cult of death that drives these movements, though, continues to grow—watered by the tears of fathers and the blood of sons. Elected to lead Hezbollah in 1992, after an Israeli helicopter-borne special forces operation led to the killing of his predecessor, Abbas al-Musawi and his five-year-old son, Nasrallah succeeded the ideological influence and power of the Islamist organisation.

As the scholar Ibrahim Al-Marashi notes, Israel’s highly successful campaign of assassination hasn’t degraded the resolve of its adversaries or reduced threats to the country. The story of Nasrallah’s life, and his inevitable killing, help understand why.

The pious son

The eldest of the nine children of Abdul Karim Nasrallah, a greengrocer who moved from Beirut from a village near Tyre in southern Lebanon, Hassan Nasrallah was born in August 1960. Abdul Karim, the scholars Lina Khatib, Dina Matar and Atef Alshaer record in their seminal book on Hezbollah, “was not particularly religious or political.” From an early age, though, Hassan developed an interest in theology and religion. Likely, he imbibed his interests from the new ideological milieu that developed in Lebanon during the 1970s, as disillusion set in with more secular Shi’a élites who had dominated the community.

Founded by Musa al-Sadr and Hussein el-Husseini together with the Greek Catholic Archbishop of Beirut, Grégoire Haddad, the Amal movement was the most visible element of the new Shi’a politics. In 1975, when a civil war that would claim over 1,50,000 lives broke out, the Nasrallah family moved back to the village of Bazouriyeh to avoid the violence. Left-wing parties dominated the village, but the teenage Hassan Nasrallah chose to join Amal.

Later, Nasrallah left for a seminary in Iraq’s religious capital, Najaf, run by the highly regarded theologian Sayyed Mohammed Baqir al-Sadr. Like other students, Nasrallah slept on the floor of a room he shared with two others, and lived on a small allowance provided by the seminary. There, he was introduced to the teachings of the leader of Iran’s theocratic revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Following his return to Lebanon in 1978, Nasrallah rejoined Amal. Four years later, though, he switched sides. Fighting Amal on the streets of Beirut for control of the camps, Hezbollah had flowered on the back of resentments caused by the displacement of an estimated 3,00,000 Shi’a people after Israel invaded southern Lebanon in 1982.

Three years later, sociologist Joseph Alagha records that Hezbollah issued a letter calling for “the establishment of an Islamic state in Lebanon modelled on Iran’s Islamic Republic.” Hezbollah also rejected conventional politics, and Lebanon’s political system. By 1989, Hassan was second-in-command of the new organisation, by some accounts more popular among the rank-and-file than even al-Musawi.

The tactic of terror

Hassan’s rise saw Hezbollah change political course, transforming itself from an Islamist resistance movement into a player inside Lebanon’s system. The organisation participated in the first post-civil war elections, held in 1992, emerging alongside Amal as one of the the two pillars of the Shi’a community. Iranian assistance facilitated that rise, with Hezbollah opening up networks of healthcare, educational institutions and even media organisations to grow its presence. Journalist Thanassis Cambanis writes that Hezbollah for all practical purposes became a national state, in whose service “it was a privilege to die.”

“At the same time,” Dina Matar writes, “he oversaw a substantial rise in the number of military operations against Israel—attacks against Israeli forces in southern Lebanon rose from 19 in 1990 to 187 in 1994, for example. In the few months before the liberation of the South, Hezbollah was launching as many as 300 attacks against Israeli forces per month.”

Leaving aside their propagandistic value, the actual military hurt caused by these operations was negligible. To Nasrallah, however, violence was a performative activity, which let him consolidate his claims to be defending Lebanon against Israel.

Faced with the long-running irritant of attacks by Palestinian insurgents from Lebanon’s south, political scientist Kirsten Schulze writes, then-Prime Minister Menachem Begin, Defence Minister Ariel Sharon and Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir succumbed to the temptation to reshape Israel’s northern neighbour by force. Their hope—contested by many Israeli military experts that the politicians ignored—was that annihilating Palestinian nationalism in Lebanon would also help wipe it out in Gaza and the West Bank.

Al-Fatah, the main Palestinian formation in Lebanon, also miscalculated—just as Hamas did last year, when it launched savage terrorist attacks against Israel last year. Al-Fatah believed Israel would respond to the attacks as it had done in 1978, when it launched limited raids to eliminate Palestinian military bases, without holding ground. This time, though, Israel deployed some 40,000 men and 440 tanks to overwhelm the 15,500 men and 110 tanks—some of World War II vintage, and incapable of movement—of the Palestinians and their Syrian proxies.

The 1982 invasion of Lebanon proved to be a disaster for both sides. “In only six weeks of combat and one year of occupation,” military historian Bradley Jacobs noted in a paper produced for the United States Naval War College, “the Israel Defence Forces suffered 3,316 dead and wounded”.

The cost in blood was demographically equivalent to the United States suffering 1,95,840 casualties in the same time frame.”

For its part, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) was forced out of Lebanon to Tunisia, where it slowly dissolved into irrelevance.

An endless war?

Eliminating the PLO from Lebanon proved a gift for Nasrallah—and a nightmare for Israel. His principal military rivals inside Lebanon now defeated, Nasrallah was able to position himself as a defender of both Islam and Lebanese nationalism. For the next decade, Hezbollah waged a successful war of attrition against Israeli forces in southern Lebanon, using improvised explosive devices and suicide attacks to effect. In 2000, with public support for the endless occupation waning, Israel finally pulled back. Hezbollah claimed it had inflicted military defeat on the Arabs’ hated enemy.

In 2006, following years of militarily ineffective but politically damaging rocket strikes by Hezbollah, Israel again invaded southern Lebanon. This time, US military officer Matt Matthews writes, Israeli soldiers who had been trained for unconventional counter-insurgency in the West Bank and Gaza found themselves fighting to standstill in a conventional campaign by Hezbollah. Although the war ended in a stalemate, Nasrallah could claim victory.

Even though Hamas positioned itself as an ally of the Palestinians after 2006, it was cautious not to cross red lines that might provoke an Israeli response that would threaten its quasi-state in Lebanon. For all its belligerence on Israel, scholar Daniel Byman writes, Hezbollah and its Iranian allies were principally concerned with defending their position inside Lebanon. The pressure grew after 2013, Byman observes, when Hezbollah’s support for President Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria alienated many Sunnis in Lebanon.

Far from being a mindless fanatic determined to dismantle Israel at any price, Nasrallah responded to events with caution. Hezbollah made loud polemical statements of support for Hamas after the violence in Gaza, but limited its military responses. Even as violence escalated in recent weeks, leading Israel to launch air strikes inside Lebanon, Hezbollah’s response fell well short of its reputed capabilities to inflict damage.

Likely, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has no intention of being drawn into another attritional war with Hizbullah. Experience has taught his commanders they are unlikely to win. Israeli commanders also know Hezbollah is unlikely to simply crumple. For its part, a battered Hezbollah knows it needs time to restitute its command structure and credibility.

For both sides, though, the death of Hassan Nasrallah is almost certainly just punctuation in a war they are nowhere close to winning.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets with @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)