The colleges in India are full to over-flowing. At the beginning of every academic year, there is a great scramble for admission, matriculates putting forward claims and counter-claims on all possible grounds, including caste and community. Judged from figures, our universities must be declared to be completely successful. Yet, it must be confessed that almost everybody is certain that the universities as they are today are unsatisfactory. Professors, students, members of our Parliament, the general public and various Public Service Commissions, are all agreed that the stuff manufactured in the universities is by no means good enough. The demands of the states are not met, although as far as numbers go, there is no question of insufficiency. There is, however, deplorable inadequacy in quality.

Democracy’s claims and all-embracing pretensions notwithstanding, sound leadership is the fundamental of national achievement and it must come from the products of our universities. We cannot seek for it elsewhere. From time to time, a revolutionary leader or saint may appear as by a miracle in the history of a nation and reshape its affairs and its character. But the day-to-day work that is required for the steady evolution of progress depends on a continuous supply of leaders who can manage men and guide the affairs of a people, and this does not belong to the realm of miracles. We want, not one, but thousands of men of character in the thousands of districts throughout the country. It would be no exaggeration to admit that the gap between the needs of the times and the quality of the supply from our universities is a yawning gulf.

The men and women who come out as graduates have to learn everything and personality has still to be shaped after they obtain employment. This is most unsatisfactory when the burden and responsibility of the public services have increased beyond the wildest imagination of the previous generation of our public men. The most important equipment that a young man must get before he leaves his university is personality, not learning but character.

Unfortunately, the atmosphere of our colleges is far too much vitiated by intellectual and moral confusion for anything like this to be attempted. There is not that guidance available, which is essential for the building up of personality in the young men and women who study in them. Their brain power is of a very high order and a tremendous quantity of learning is put in, but the essential stuff is wanting.

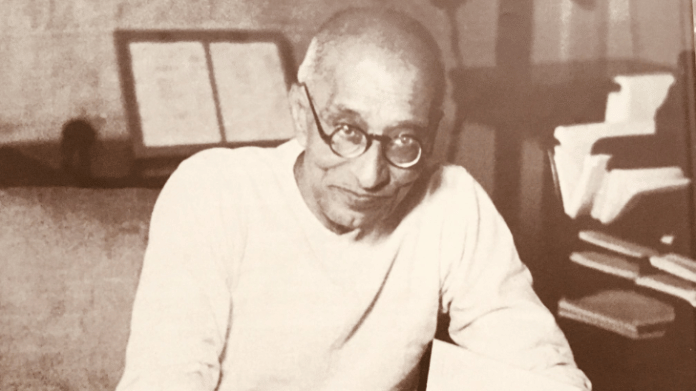

Also read: Remembering C. Rajagopalachari, independent India’s first and last Indian Governor General

The explanation offered is that there is so much intellectual and moral confusion in the world around them that this is reflected in the universities. But is it enough for universities to reflect outside confusion instead of making up for it? The function of the universities must be to reform, not to represent society proportionately but to do something to restore moral values and intellectual orderliness where there is anarchy.

I once again emphasise that the universities must give the nation the leaders, teachers, and administrators who are required in this complicated age to fulfil the duties devolving on the State and to guide society in its cultural life. Folly must be replaced by reason, passion must be put aside in favour of reflection, ideals must be installed where caprices govern, in fact principles must prevail, not opportunism. All this cannot be accomplished for us through some mighty miracle. It is the function of universities to produce the young men and women who will be able to find joy and fulfilment of spirit by guiding the people up this glorious mountain path.

The young men of today are the sport of random and confused thought that finds expression in ephemeral printed matter of whose undependability even the victims are not unaware. In the great experiment which, in the evolution of her destiny, India has undertaken to make in our generation, there is nothing more unfortunate than the present state of our colleges and universities. They were planned and built in a past generation and it is no fault of theirs if they do not suit our times, and have not gained, but rather suffered, by the revolutionary technique that was evolved for the speedy attainment of freedom.

Had our philosophy and our culture, which formed the great bulwark which protected India through past ages been intact, the mischief arising out of the inadequacy of our universities might have been of relative unimportance. If our Vedantic culture had been kept alive, not in scholarship alone but in the hearts of men and in their deeper understanding, no deficiency in school or college education would have resulted in serious harm. Unfortunately, this ancient inheritance has become a rapidly diminishing asset. Little of it, I fear, is left now. Otherwise we should not be witnessing the vast quantity of greed and selfishness that have made the aims of our national government so difficult of achievement. The discipline and restraint and the sense of moral values, which Vedantic culture implies, have been almost completely jettisoned by the steady and unrelenting educational plans pursued during the last fifty years, which, alas, did not furnish us with anything in place of the old inheritance that was thrown overboard.

Also read: Leave education to universities, limit UGC role to grants—SN Bose in Rajya Sabha

All learning should develop personality, otherwise it is worthless in every sense. On the other hand, if this aspect of university aims be kept in mind, every variety of study will be rich in fruit. Be it science, technical training, economics, history, law, domestic science, or whatever else it may be, it would—each one of these—be an ample field for making a boy or girl a leader of men, provided that, along with intellectual equipment, the development of personality received attention.

I am not unaware of the difficulty of providing moral training. We cannot get the right type of personalities to live and move among the youth gathered in the universities, whose very lives and deportment, without direct instruction or the compulsion of discipline, would be an inspiration. We get teachers who are vastly competent in every other respect, but the greatest reluctance is generally felt in introducing anything in the scheme of school or college education, which may be mistaken for denominational religious teaching. One must recognise the validity of the reasons and apprehensions that lead to this, but we cannot afford to exaggerate our fears and rest content with doing nothing.

The Crisis is far too real and grave. We cannot take a simple negative attitude on account of our hesitations. I feel that there is a way to achieve our object. A comprehensive scheme for the creation of opportunities to study and understand various religions and philosophies, including that which goes by the name of classical humanism in the Western universities, namely, the thoughts of Greece and Rome, would, taken together, furnish an atmosphere and an incentive, which would enable our boys and girls to seize the truth and to assimilate the culture and philosophy of our own land, without any exclusive or direct effort organised for that purpose.

The indirect approach may achieve that which cannot be directly undertaken. Let our boys be encouraged to interest themselves in the literatures of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and the classics of Greece and Rome. Then, without being asked to do so, they will recapture the Vedanta for themselves, for it is still available for recapture by anyone born in India and who is blessed with enlightened pride.

When straying from the studies prescribed for me when I was young, I read Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, and chapters in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, and later I acquainted myself with the thoughts of Socrates, Marcus Aurelius, and Brother Lawrence, and although no one incited me to it, the joy and reverence which these things induced turned me towards the Upanishads, the Gita, and the Mahabharata.

All spiritual search is one and God blesses it wherever and by whomsoever it is done. If I am today a devout, though very imperfect Hindu Vedantin, it is no less due to my contact with some of the sacred books of other people, than to the contemplation of what our own great ancestors have left us. Not by total exclusion from all religious and spiritual thought, but by an all-embracing acquaintance with and appreciation of spiritual thought of all kinds, shall we be safe and shape ourselves properly.

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.