The greatest impact of the Industrial Revolution was not on industries but on governments. Realigning economic and social equations redefined how power was accumulated and wielded. This resulted in the rise of several political theories and governance models – some of which have survived and others faded away. Today’s technological advances, a technology tsunami, are just as transformative. Data is now the most powerful currency, while technology has permeated every aspect of social life. Using technology, governments can do more with less while facilitating greater participation, transparency, and accountability. We have now entered an era of technological disruption in government.

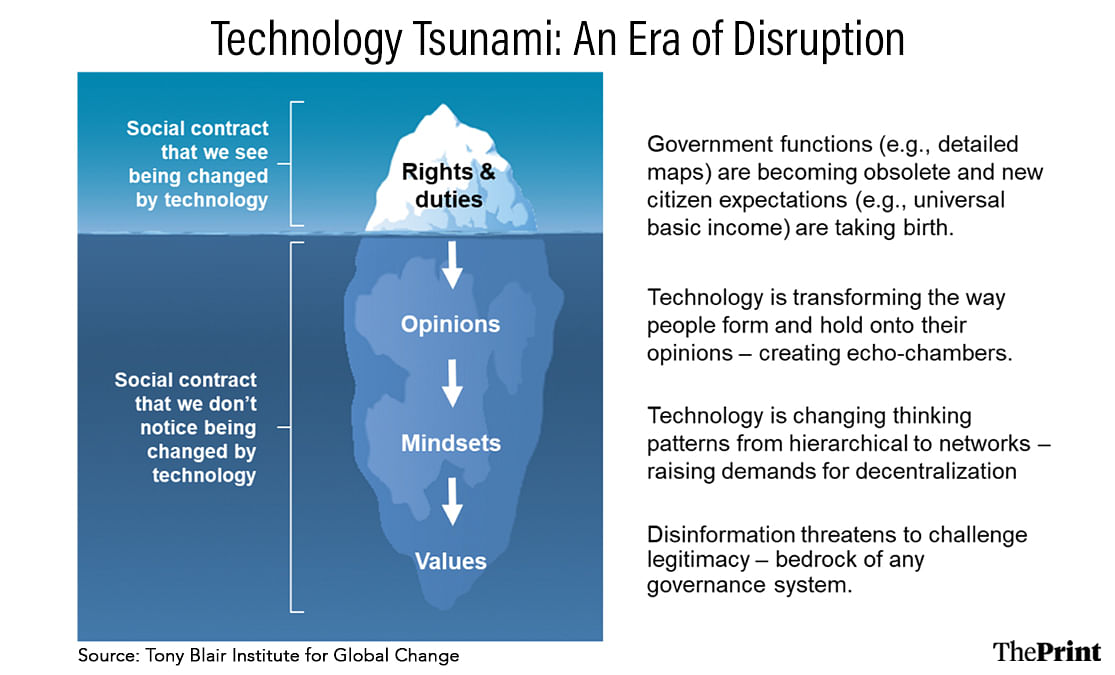

This era isn’t just about changing the status quo; it’s about fundamentally altering the social contract — the implicit agreement between government and citizens about rights and duties. One might liken this disruption to the radical technology-led transformation of age-old industries like logistics, hospitality, and retail (think Uber, Airbnb, Amazon). Just as young entrepreneurs upended these businesses with no prior business experience and operating out of humble garages, so too is the government by technological innovations that proliferate despite it.

Advances in technology have resulted in subtle yet swift changes in expectations of citizen’s rights and duties. While some government functions are becoming obsolete, new citizen expectations are rising. Governments are no longer the single source for detailed and accurate maps. Through a multitude of non-government sources powered by advances in satellite imagery, government monopolies are fading and high-quality maps are becoming available free of cost. Conversely, recent breakthroughs in generative AI have an extraordinary capacity to reshape existing employment patterns. Only time will tell whether these breakthroughs will have a net result in deskilling of the workforce due to a rise in demand for microtasks (e.g., data annotation) or upskilling thanks to technological assistance in replacing (at least) basic tasks (e.g., data science). For now, it has reignited demands for a universal basic income – an addition to the list of expectations from governments.

Part of this expectation shift has been driven by how technology, particularly social media, transforms how people form and hold onto their opinions. It may seem like social media is just a more efficient version of print media. Physical constraints like paper don’t limit social media; it doesn’t require accommodating editorial bias and can provide real-time updates. However, this increased capacity to share information — in greater quantity, at faster speeds and with more diversity has paradoxically led to shallower opinions, a breaking news culture with limited regard for accuracy, and opinions being misconstrued as facts.

Further, the casual nature of face-to-face conversations has been replaced by the permanence of digital posts that can be examined for inconsistencies years later. Additionally, algorithms that prioritise engagement tend to reinforce existing beliefs by creating an echo chamber of similar views — leading to the polarisation of opinions. All of this has led to a rapid change in what people have come to expect of their governments.

Also read: India solves one problem, adds another while using AI for climate crisis. Clean up data first

A state of political decay

The social contract, however, isn’t just a roster of duties and rights; it also embodies a society’s mindsets and values. Prominent psychologists and anthropologists argue that technology, particularly the internet, has changed human thinking patterns from linear hierarchical structures to interconnected networks. This change in thinking is one reason for transforming mammoth bureaucratic systems into agile networked structures. The recent and growing interest in technologies like blockchain, the basis of Bitcoins, is centered around its lack of centralised authority that can be corrupted and is beyond scrutiny. This trend, reminiscent of the Occupy Wall Street movement, indicates a shift in values about government authority, moving from centralised to decentralised forms of authority. A multitude of participatory platforms, such as FixMyStreet (UK), MajiVoice (Kenya), and Sag’s Wien (Vienna), channel this mindset and reduce the distance between citizens and the state.

Finally, the social contract is premised upon legitimacy – a widely acceptable notion of what constitutes a proper government. Technology has driven a paradigm shift in information access – from limited information to information overload and, more recently, to misinformation. Fake news has influenced elections globally, from the United States to Bangladesh and France to Nigeria. We have now ventured into the realm of the unverifiable with technologies like deepfakes. Sophisticated deepfakes, so convincing that even technology struggles to identify them as fabrications, render us incapable of verifying authenticity.

Attempts to tackle this through ‘watermarking’ real pictures and videos have limited success. The realm of the unverifiable is a severe threat to the legitimacy of governments, as citizens grapple with distinguishing the true from the untrue.

Political theory warns of political decay when the rate of social advancement exceeds the rate of institutional change. It may be premature but it won’t be an exaggeration to say, collectively, we are entering a state of political decay. Governments, as we understand them today, the ultimate arbiter, centralised monopolistic authority, will have to make way for a new form of government.

Engels’ vision of a future where “government of the people” transforms into an “administration of things” could hardly have foreseen that the inexorable force of technology could power this transition. His notion of the “withering away of the state” was originally rooted in the context of a classless society. However, the current technological tsunami threatens to do just the opposite: It may well exacerbate the gulf between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’, effectively birthing a new socio-economic stratum. Yuval Harari takes this concern to an even more provocative extreme, positing that recent breakthroughs in AI might steal away human agency and ultimately herald nothing less than the “end of human history”. Even without venturing into the realm of far-fetched scenarios involving cyborg dominion powered by Musk’s Nerualink or quantum computing upheavals toppling financial security systems, one thing remains abundantly clear – technological advancement is outpacing the ability of government institutions to adapt and evolve.

The author heads the India practice for the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. Views are personal.

This article is part of a series on AI tech policy and impact as part of ThePrint-Tony Blair Institute for Global Change editorial collaboration.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

You have a shared a lot of absolutely brilliant aspects and thoughts, Vivek. Thinking process becoming shallower is definitely a bad trend and powerful people in Govt misusing the so-called flood of information from the ocean of data for more paper or to stay in power, is another continued disease. Worse is the attitude of young people becoming selfish and doing thing only fir their benefit, without bothering to see the larger picture emerging. And we certainly don’t need role models like Musk. How can we make younger generation aware of the fallacy of AI at the deep root level?