The 22nd anniversary of India’s nuclear tests, on May 11, went unnoticed mostly because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. But some with elephantine memories did look back at that hot summer of 1998 when the Bill Clinton administration leaked a letter to The New York Times, written by then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, telling the US president why India had gone overtly nuclear in the first place.

India’s “bitter” relationship with its neighbour up in the north, Vajpayee wrote, had been the driving force for the nuclear tests at Pokhran, surprising many in the Western world who believed that India was largely driven by its preoccupation with Pakistan next door. But Vajpayee and his team of strategic thinkers, once they had dealt with the 1999 Kargil invasion as well as the hijacking of the Indian Airlines Flight 814 later that year, had been consumed with how to rethink the unequal relationship between the world’s largest democracy and a Communist nation next door.

If anything, the difference between India and China has only grown — every economic indicator will tell you that. China’s $13.6 trillion GDP (in 2018) contrasts significantly with India’s lowly $2.7 trillion GDP. That’s why India won’t take sides in the ongoing US-China spat about the origins of the coronavirus — in a government-controlled lab in Wuhan or at the wet markets in that city— or whether it should be punished for not telling the world about the coronavirus sooner.

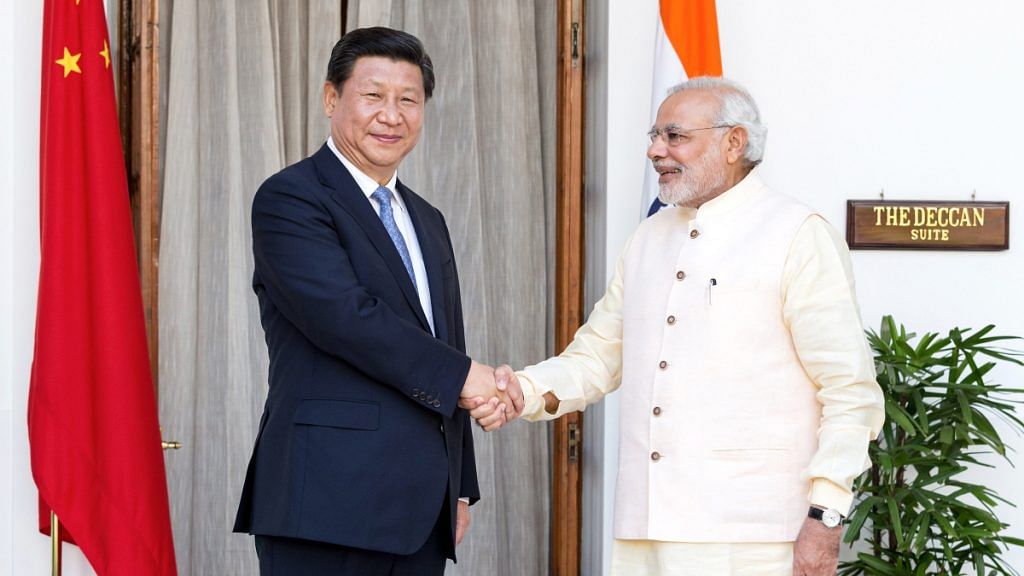

The simple reason why India won’t take sides is because it needs China far too much — despite the RSS’ economic wing Swadeshi Jagran Manch insisting that India should bring down its dependency on China and despite efforts to attract firms shifting out of China. The hugely unequal trade deficit between the two countries, currently at $53.57 billion, is enough to deter the most nationalist of leaders, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

So, when Chinese soldiers barged across a windy mountain waste at the Naku La pass (not to be confused with Nathu La) in north Sikkim over the weekend or engaged in fisticuffs with Indian soldiers in Ladakh’s Panggong Tso lake a week ago, it was time to wonder why the Chinese were behaving so aggressively across two sites on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) separated by more than 2,500 km.

China had succeeded in demonstrating one fact — its military’s ability to mount angry expeditions on high-altitude terrains across large distances. It brought back memories of the 73-day-long standoff on the Doklam plateau in Bhutan in 2017. The standoff was resolved by both sides withdrawing their troops. Neither side won, but India held its nerve. That was already a victory.

Also read: Indian, Chinese soldiers injured in Sikkim’s Naku La after ‘exchanging blows’, stone-pelting

Conflict map that China draws

So, what to make of the recent skirmishes? First, they are not new. They have been taking place over the last several years, including the final years of the Congress-led UPA-2. Second, they are a violation of agreements, written down in black and white, which delineate how both sides will deal with differences on interpreting the undemarcated LAC (first disengage, then return to your bases). Third, the Chinese soldiers walking into Indian territory in Sikkim and Ladakh — which they believe to be Chinese territory — seem very angry and very eager to pick a fight.

As former national security advisor and China expert Shivshankar Menon said during the Institute of Chinese Studies-ThePrint Conversation last week, “When do leaders shout? When they are nervous and uncertain.”

In Sikkim for instance, the border between India and China is settled, including in the maps that the Chinese have put out since 2005. But because both sides have still not been able to demarcate the LAC as a four-grid line on a map — despite the fact that since 2003, special representatives from both sides have had annual conversations on what to do about this — Chinese PLA troops decided they would walk across the Naku La pass and rough up the Indian soldiers.

Also read: India’s labour reforms trying what Bangladesh, China, Vietnam did — swap income for security

Why Naku La matters

What is interesting about Naku La is that it was the subject of a British expedition as far back as 1902 and directly dealt with Tibetan representatives on territorial claims. The Political Officer for Sikkim, J.C. White, travelled there on 15 August 1902 and again, three years later, to finalise the subject of grazing rights between the people of the Lachen valley (inside Indian territory, just south of Naku La) and the Tibetans.

“I would interfere very little, if at all, with the old customs, and would allow the Tibetans to bring in their yaks to graze at certain times of the year, provided they allow the Sikkim people to do the same in Tibet, as was formerly done,” White wrote to the secretary of the government of India in the foreign department.

The number of pillars needed to demarcate the boundary would only be 10, including one on Naku La. In the end, 23 “cairns,” or piles of stones all along the ridge line, were placed.

Nearly one hundred years later, when Vajpayee went to Beijing in 2003 and the question of Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh in the eastern sector of the LAC came up, the J.C. White school was resurrected as both sides discussed, not just the possibility of exchanging maps along all sectors of the LAC but also allowing Tibetan pilgrims to cross back and forth across a possibly porous border.

Nothing came of it, of course.

Vajpayee would be more successful on India’s western border with Pakistan, by pushing for an opening across the Line of Control — even though it would be a Congress-led UPA that implemented that decision in 2005, by sending the first bus from Srinagar to Muzaffarabad.

Also read: Modi reviving NAM won’t be enough in post-Covid world. India must reconsider joining RCEP

Testing the waters

Fifteen years on, as the world grapples with the coronavirus, it is interesting that the Narendra Modi government has all but abandoned Vajpayee’s thinking on Pakistan, but continues to take a leaf out of his “trust but verify China” book by refusing to join the US-led blame game on the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic and demonise China.

Perhaps the skirmishes in Sikkim and Ladakh are the Chinese testing the waters, looking to see what India will do and how far it will go in handling these provocations. The Doklam standoff should be a good ready reckoner in that Delhi will refuse to budge on sovereignty issues, but leave one door open for diplomatic conversation, even if the conversations, either in Wuhan or in Chennai, don’t even begin to resolve any of these issues left over from history.

Also read: India looks to lure US businesses from China as Trump keeps up tirade on coronavirus

It’s China’s choice

Perhaps the real problem is that China refuses to recognise the shades of grey in its relationship with India and the rest of the world. Compromise is seen as weakness, give-and-take as vulnerability. The Chinese believe they are on the right side of history and can afford to play the long game. That’s why they debunk all the historical records written by the British, on Naku La and elsewhere and believe history is written by the victors.

But in the brave new world being reshaped by a mere virus, Beijing needs to understand that the old rules may no longer work. Much is being made of Shanghai’s Disneyland reopening Monday, as if China has won the first prize in the global consumer sweepstakes, but the fact is that its reputation of being a responsible power is at stake. Can China bully its way into the new world order? Will the Chinese people demand answers from their leadership, like the Soviets did from their own in 1991?

Or is Covid-19 the anvil on which a new hegemon will rise?

Views are personal.