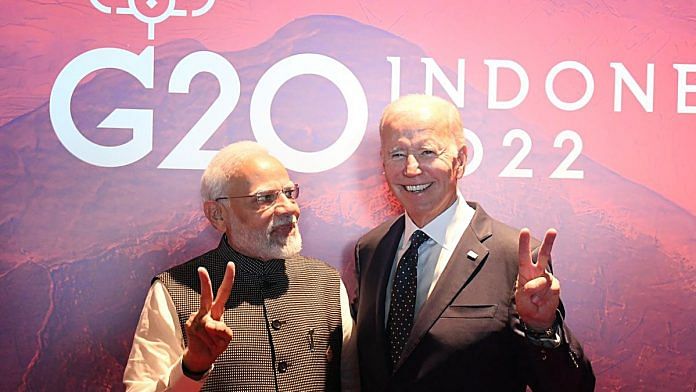

India has undoubtedly had a successful G20 meeting at Bali. Its role in finding a middle ground between the Russia-China axis and the West has been widely applauded. Many commentators suggest that the role India played in Bali signals its rise as a new power. There is some expectation that New Delhi can potentially bridge the emerging East-West conflict, especially in the service of the Global South, something Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself emphasised. Nevertheless, there is also a need for caution. The pursuit of such a bridging role in the G20 may bring New Delhi some status but it could potentially risk India’s security by distancing it from its key security partners—all in pursuit of an elusive middle ground.

To begin with, leading the G20 is itself no great achievement, nor a recognition of any special Indian merit or global stature. Remember that New Delhi is taking over the presidency from Indonesia, which took over from Italy, two countries that are no doubt important but not exactly global powers. These kind of positions are of fairly limited value in international politics, especially for complex groupings that include multiple great powers and interests. This automatically means that very little of substance can actually be achieved, save lofty declarations. In the context of the emerging great power competition between the US and its allies and partners on one side and China and Russia on the other, the relevance of the G20 is rather doubtful. Great power competition will likely encompass everything and the G20 will be no different. This means that not only will India be asked to take sides but New Delhi will also seek a middle ground that could hurt its security partnerships. This is a problem because India may revel in its pursuit of the middle ground to the point of losing sight of its security interests.

Look beyond ‘status’

Much of New Delhi’s focus, whether it is the G20 or a permanent UN Security Council seat, appears focused on the prestige and status that supposedly come with such a position rather than anything that is of material substance. Think back to the much ballyhooed Indian “leadership” of the Executive Board of World Health Organization (WHO), which came in the early months of the Covid pandemic in 2020. India could have actually provided some leadership and held China’s feet to the fire, especially considering the latter’s aggression in Galwan in June that year. That would have not only done a global public good — helping throw light on the suspicious origins of the virus and Beijing’s efforts to suppress the investigation — but also helped Indian interests by undermining China. What India actually did with its leadership of the WHO Executive Board remains a mystery. But there is little indication that it took advantage of that opportunity. It would appear that New Delhi’s objective was the position itself, rather than what the position could do for Indian interests.

The central question for India’s foreign strategy in the foreseeable future is how to secure the country against China’s military threat and its pursuit of political hegemony in Asia and beyond. Everything India does must be viewed through this prism. But India has often prioritised international status rather than national security. It has been enamoured by the mirage of a global role that provided little material benefit either in terms of wealth or security. Worse, it has often assumed that such a role would cloak India from having to make difficult and expensive choices in international politics.

New Delhi is yet to make a proper assessment of what it actually gained with its third world activism from the 1950s onwards. How did India’s mediation in the Korean War or its leadership in NAM or the G77 benefit Indian interests materially? In times of trouble, as in 1962 and 1971, India was forced to face up to the reality that its security gained not one whit from whatever status it had as a leading third world “power”. The only friends that mattered then were the ones who were willing to militarily and diplomatically back India, not the ones who voted with India in various and numerous inane peace proposals at the UN General Assembly.

Despite some changes in India’s approach to the outside world, much remains unchanged, as scholars of Indian foreign policy have correctly pointed out. One such element is the continuing focus on status, even if the specific basis on which that status is sought may have changed.

Also read: G-20(24): How ‘Vishwaguru’ can get new strategic space & Modi another stage in pre-election year

Crises and the test

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with the pursuit of status. But it is a luxury that only those states that are sufficiently secure should pursue. The problem is when such pursuits come in the way of more urgent needs of national security. Status, by itself, provides no security in the rough and tumble of international politics.

At least in the early decades of Independence, India was a relatively more secure State, which at least had the potential to be able to defend itself, even if this was often frittered away. This condition no longer obtains. India’s security circumstance has progressively worsened over the last three decades, as it has weakened steadily vis a vis China. This means that India cannot afford any foreign policy goals that divert it from its most fundamental interest of securing itself from China’s power.

It isn’t as if New Delhi doesn’t realise that its security condition has worsened. In fact, that is the basis of India’s increasing closeness to the US and its allies, its membership of the Quad and many other actions besides. Indeed, even as India was playing the mediator in Bali, the Indian Navy was conducting the Malabar military exercises with its Quad partners off the coast of Japan. These are the critical partnerships necessary for Indian security and nothing should be allowed to come between India and these security partners.

Whatever status India had in the 1950s itself suffered a grievous blow when it couldn’t defend its territory in 1962. India’s security circumstances are a lot worse today, which means it has a much narrower margin for error. India needs much clearer focus on what is truly important for its national security interest. Being a mediator or a bridge or a spokesperson for the Global South may not be worth it.

The author is a professor of International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. He tweets @RRajagopalanJNU. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)