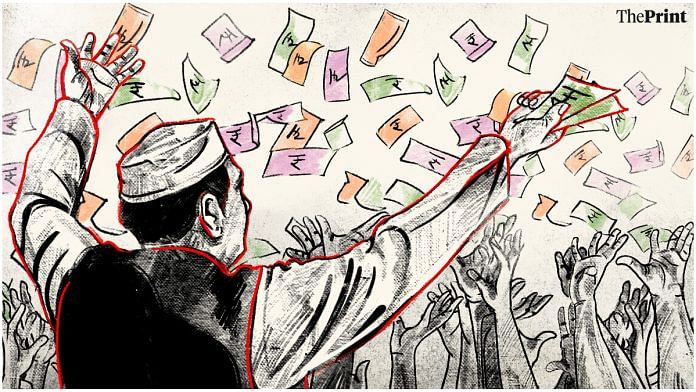

With half-done economic reforms not delivering the East Asian growth rates of old, and with manufacturing, merchandise exports, and employment all lagging despite government efforts, the big idea that politicians have re-discovered with a vengeance is the old one of fiscal transfers through price subsidies and cash payouts. They are encouraged in this because they have seen, over and over again, that it works at election time.

Perhaps the first electoral triumph built on this approach was by the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), in what was then Madras state in 1967, when it promised rice at a rupee a measure — a promise not delivered beyond the state’s capital, because it was unaffordable.

M.G. Ramachandran, after he broke away from the DMK to form his own party, vastly expanded a limited programme of free mid-day meals in schools. This had many spin-off benefits: Improved nutrition, better school attendance, and therefore improved literacy, even a lower birth rate; it is now a nationwide programme.

In 1983, N.T. Rama Rao in Andhra Pradesh took a leaf from the DMK’s playbook, sweeping the Assembly elections with the promise of rice at Rs 2 per kg.

In recent years the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has failed to deliver on macro promises (like doubling farmers’ incomes, or a $5 trillion economy) and therefore stressed its own welfare package: Cash payments to farmers, free foodgrain, free toilets, subsidies for housing, free medical insurance, and so on.

But it decries as “revdis” (freebies) similar actions by other parties even as the Congress (which introduced a rural employment guarantee) copies the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) on free power for specified domestic consumers.

In the recent Karnataka elections, the Congress promised Rs 1,500/Rs 3,000 a month to every jobless diploma-holder/graduate, Rs 2,000 a month to every female head of a family, free electricity, and free grain. Elsewhere, parties have offered free TV sets, smart phones and laptops, gold and cattle, fans and bicycles.

The voting public approves, judging by the electoral record in state after state, and nationally in Lok Sabha elections. The next round of state elections will see more welfare promises and freebies. The broad approach seems to be that if the economy can’t generate enough jobs, and if the education and health care systems fall short, then the way to win elections is through welfare transfers and free goodies.

The obvious counter is that these are a poor substitute for jobs, quality education, and health care. But if the state can’t find a way to deliver those, then welfare schemes are unavoidable. That is how a democratic system keeps a lid on economic distress and social unrest.

Also read: If consumer confidence is a political bellwether, are current levels enough to help BJP win 2024?

It might even be argued that India is moving in an unplanned and haphazard way towards setting up a social safety net, with the free provision of grain and medical insurance; public works programmes to create work; cash payments to vulnerable sections like the old, indigent, and unemployed; plus free or subsidised access to basic goods like electricity and cooking fuel, even housing.

And who can complain? In an economy where poverty still exists and inequality has grown, and (as Thoreau wrote in the mid-19th century) “most men lead lives of quiet desperation”, such a welfare system is surely preferable to spending tens of thousands of crores to cover the losses of Air India, the government-owned telecom companies, and the government’s banks.

The constraint, as always, is money — as even wealthy countries are discovering with regard to their welfare systems.

Prosperous Delhi can afford free electricity, but can debt-ridden Punjab? The question that the prime minister posed when decrying “revdis” is also valid: Are these freebies at the cost of investment in the infrastructure required for a modernising economy?

Put another way, is India creating a sufficiently large productive economy that generates the taxes to pay for a welfare system? The answer is that the tax-to-GDP ratio has shown little improvement, despite a quadrupling of per capita income over three decades.

So are we simply piling up public debt, servicing which eats up about 40 per cent of tax revenue? There is an urgent need for public debate on this central political-economy question. The NITI Aayog or a private think tank should take the lead.

By special arrangement with Business Standard.

Also read: FY23’s positive GDP data hides worrying trends: Weak consumption, sustained slump in manufacturing