China’s crude oil imports compared to a year earlier represents growth of about 1.2 million barrels a day, so even slower domestic demand growth can have an outsized impact on global markets.

Forget Iran, shale and Opec. The real action in the oil market is happening on the other side of the globe.

China overtook the U.S. as the world’s largest oil importer last year, and for 2018, it’s hoping to beat that achievement. April imports of 39.46 million metric tons reported late Tuesday came off the back of a string of blockbuster months. Until the start of this year, China had never imported much more than 37 million tons in any single month. So far in 2018, only February, shortened by the Lunar New Year holiday, failed to exceed that amount.

It wasn’t meant to be like this.

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) and the International Energy Agency expect China’s demand growth to start slowing toward an annual pace of 300,000 additional barrels a day over the next few years as the nation switches from its headlong pace of industrialization and the rise of electric vehicles crimps gasoline demand.

Opec revised its numbers upward for 2017, and the same may happen this year. The 5.1-million-ton increase in China’s April crude imports compared to a year earlier on its own represents growth of about 1.2 million barrels a day.

A few things might help account for this. China’s domestic oilfields are struggling to keep up with demand as wells get tapped out and the government pushes the big three state-owned firms to instead produce more gas. As a result, the country is leaning more heavily on imports – so even a slower pace of domestic demand growth can have an outsized impact on global markets.

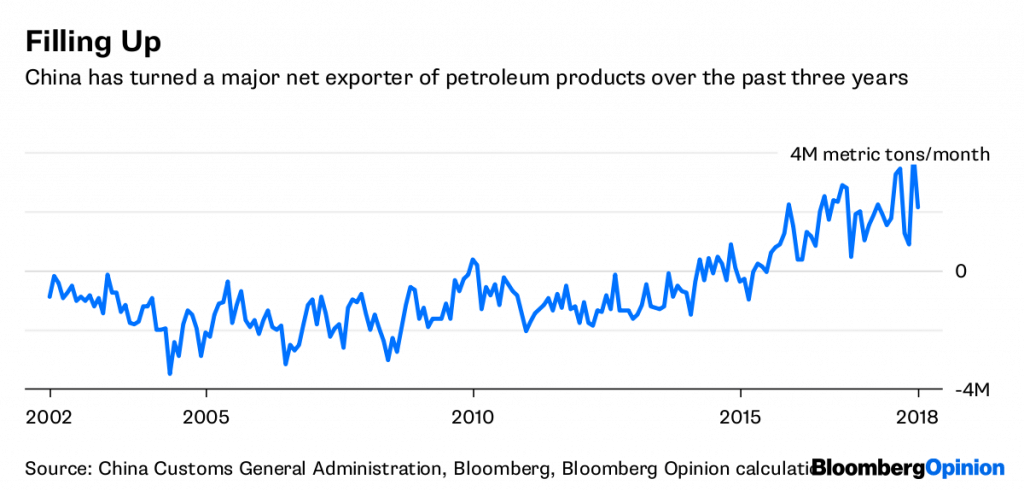

Another factor is that much of this crude isn’t ultimately being consumed in China. Exports of refined products have been surging as authorities relax quotas on the trade, with Morgan Stanley analyst Andy Meng estimating that the volume of products permitted under export quotas granted in 2018 already exceeds the total for the whole of last year. In that sense, this isn’t so much a story of China’s booming domestic demand as the perennial habit of its manufacturing sector to go over-capacity.

The 26 million tons of net product exports over the past 12 months would be enough to turn a country that was until a few years ago one of the larger importers of refined petroleum into a major exporter on a par with South Korea, Kuwait and India.

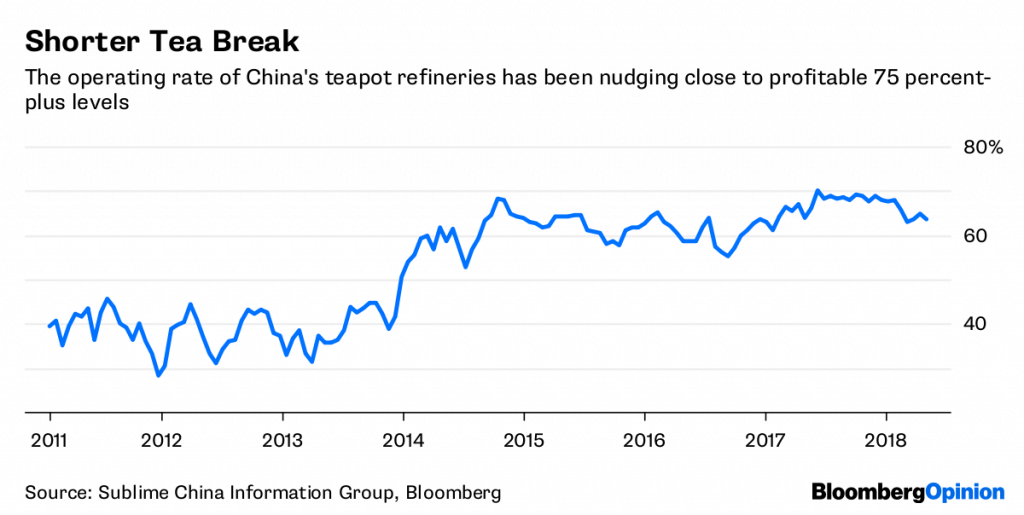

Even China’s teapot refineries – non-state-owned plants mainly in Shandong province, which are traditionally operating less than half the time – have been seeing operating rates nudging close to levels where they should be able to make a profit.

The sanguine response of oil prices to news of President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the 2015 accord on Iran’s nuclear program has been explained by the fact that the decision was widely expected, and that crude tends to find a way round such restrictions. The strength of Chinese demand – in particular, whether the current strong figures play out over the course of the year or represent a short-term stock build – could prove a decisive factor on that front.

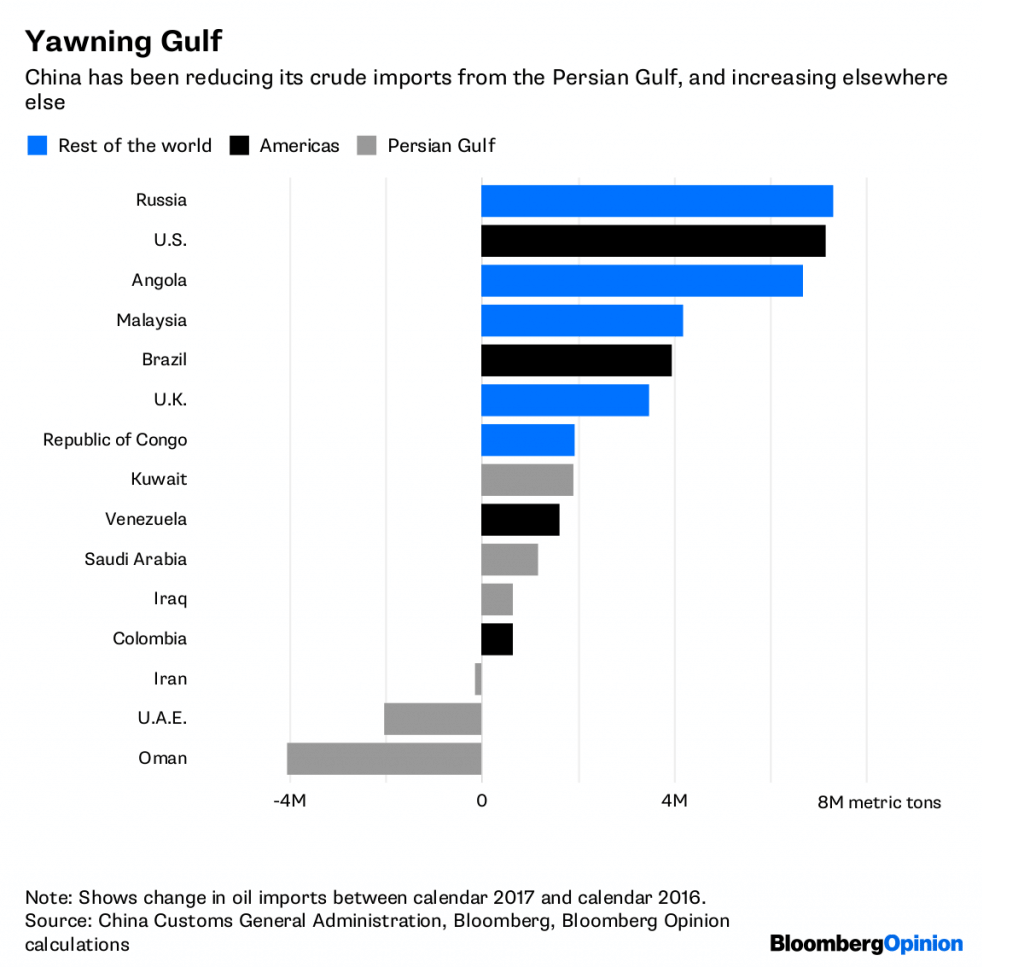

The yuan-denominated crude contract recently launched in Shanghai may be one of the easiest ways for Iran to get past U.S. sanctions, which are typically enforced when banks attempt to clear dollar-denominated trades in New York. Beijing has been shifting its oil purchases away from the Persian Gulf and toward Russia, the U.S., Brazil, Angola and Malaysia in recent years, but a sudden lack of Western buyers would be the perfect opportunity for Chinese refiners to get back into the market for Tehran’s crude.

Looking at supply is crucial for understanding crude, but it’s not everything. Right now, the strength of China’s demand may be the most under-appreciated story in the market. —Bloomberg.