The day after he learned his son’s bullet-riddled corpse had been buried in an unmarked grave in Kashmir, Abu Asiram’s father invited his friends to celebrate his marriage to the Houris of Paradise. The long months of his training in a Lashkar-e-Taiba camp had been his mangni or engagement. A few days before his death, it was said, his mother had a vision of her son dressed in beautiful white clothes, surrounded by trees and flowers, drinking milk—a scene that evoked a familiar Punjabi wedding ritual.

Like it has so often in the past, India this week has been considering how to respond to savage violence inflicted by the Lashkar’s cult of death. The killing at Baisaran Maidan in Pahalgam is far from the first mass killing where jihadists executed victims picked because of their Hindu faith: hundreds, after all, have been similarly killed in the course of Kashmir’s long jihad.

The Pahalgam killing, though, poses a strategic problem. Ever since troops struck across the Line of Control in 2016—followed up by an air strike three years later—India believed it had drawn red lines for which Pakistan’s Generals would ensure their jihadist proxies would not cross for fear of war. Since 2016, there have been no jihadist attacks outside Kashmir. For five years after 2019, violence inside Kashmir diminished to negligible levels.

Little imagination is needed to see that the tempo of killing is picking up again, though. There has been a string of ambushes targeting Indian troops, as well as strikes on Hindu pilgrims and villagers. And inside Pakistan, the Lashkar has reemerged from the box it was hidden in as the country faced the risk of international sanctions and again began to celebrate the deaths of its cadre in Kashmir.

Two questions are key to shaping a response. First, did India really succeed in coercing Pakistan into respecting its red lines on terrorism, or did Pakistan merely engage in tactical pauses to suit its ends? And, if so, what might a genuine coercive strategy look like?

An addiction to jihad

From the moment of its birth in 1947, the Pakistan army engaged in the political mobilisation of Islam. Local clerics, the historian Ilyas Chattha has recorded, helped mobilise the ethnic Pashtun militia and demobilised British-Indian army soldiers who waged war in Kashmir. The use of Islamic themes was central to the long covert war waged in Kashmir by Pakistani intelligence, leading up to the invasion of Kashmir in 1965. As scholar C. Christine Fair has shown, the Pakistan army sees itself as a custodian of this jihadist national ideology and the instrument of its execution.

Even when engaged in a war against jihadists who have turned on the state, the army sees the broader movement as an ally. Thus, in 2014, Xi corps commander Lieutenant-General Syed Safdar Husain garlanded the jihadist Nek Muhammad Wazir—only recently responsible for the killing of dozens of his troops—as though welcoming home a prodigal son.

“When India attacks Pakistan, if you look into history, you will see the tribals defending 14,000 kilometres of the border,” Nek Muhammad promised in turn. “The tribal people”, he went on, “are Pakistan’s atomic bomb.”

There is no doubt that General Asim Munir has rolled back restraints on jihadist operations in Kashmir. “Three wars have been fought for Kashmir, and if ten more need to be fought, we will fight,” he declared at a Kashmir solidarity event in February.

Language like this, though, isn’t unusual in Pakistan’s establishment. Former army chief General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, who rolled back the India-Pakistan detente process initiated by his predecessor and presided over 26/11, expressed pride that “the nation has never forgotten the sacrifices of its martyrs and holy warriors.”

“There is no greater honour than martyrdom,” he insisted, “nor any aspiration greater than it.”

General Raheel Sharif, Kayani’s successor, told an audience at General Headquarters in Rawalpindi that “Kashmir is Pakistan’s sheh rag, or jugular vein.” To him, it was apparent that war in Kashmir was “nothing less than a struggle for the very existence of Pakistan as a viable nation-state.” Lasting peace, he later argued, “is impossible without the solution of the Kashmir issue.”

These sentiments were not uncommon among the wider political élite, either. Top politicians and bureaucrats, leaked American diplomatic cables revealed, participated in Lashkar activities as late as 2007. The then-Defence Parliamentary Secretary said he was “proud to be a member.” The leaked cables also show that Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, then chief minister of Punjab, helped the Lashkar evade United Nations sanctions in the weeks after the 2008 Mumbai attacks.

Two chiefs—General Pervez Musharraf and General Qamar Javed Bajwa—did indeed respond to coercion. Following the near-war of 2001-2002, General Musharraf initiated a ceasefire on the Line of Control and began a political dialogue aimed at ending the conflict in Kashmir. General Bajwa, for his part, reached out after the 2019 airstrikes to begin an ISI-Research and Analysis Wing dialogue.

Little evidence exists, though, that either felt militarily defeated in Kashmir. First-person accounts gathered by the scholar George Perkovich suggest General Musharraf believed his nuclear weapons had successfully deterred India in 2001-2002. He chose dialogue on Kashmir because the crisis damaged his plans to develop Pakistan. Likewise, General Bajwa privately told journalists the Pakistani economy simply could not sustain a war. Theirs were pragmatic, tactical manoeuvres—not changes of heart.

Five fateful choices

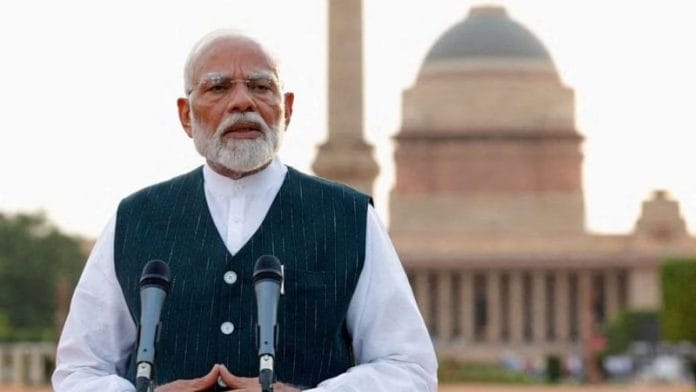

Five choices now face Prime Minister Narendra Modi after the Pahalgam attack—each of which India has already attempted, with mixed results. First, he could authorise airstrikes on Lashkar facilities around Muzaffarabad or even its sprawling headquarters complex at Muridke, near Lahore. There is, however, no certainty that this will impose significant damage. The 2019 bombing of the Balakote seminary, after all, failed to hit its targets, demonstrating the continuing problems that confront precision bombing. Just as crucially, the Pakistan Air Force proved it could hit back: There is no guarantee of victory.

The second option, similar to the one used in 2016, would be to authorise limited strikes by ground forces across the Line of Control. This would involve fewer risks than air warfare but also uncertain gains. The unravelling of the ceasefire on the Line of Control, put in place by General Bajwa after 2019, would make infiltration easier for jihadists since they would be able to take advantage of covering fire on Indian Army positions.

Moreover, India has a long history of staging ground strikes, with limited results. India regularly staged unpublicised retaliatory actions across the Line of Control before 2016, for example, destroying Pakistani forward posts after the kidnapping and beheading of its soldiers in raids by that country’s special forces in 2011 and 2013. These did not diminish terrorist violence.

Third, the Prime Minister could authorise the use of covert means, like the assassination of top jihadist leaders. This is a strategy India is believed to have pursued with considerable success in recent years. Though this helps punish perpetrators of violence, there is no evidence it retards terrorist operations in the long term—a lesson Israel has learned in Gaza and Lebanon.

Fourth, India could consider wider, more conventional operations of the kind it contemplated in 2001-2002, but more carefully crafted to avoid the problems of mobility and escalation that undermined the effort. General HS Panag has suggested a limited offensive campaign along the Line of Control could impose punitive reputational and military costs on the Pakistan army while minimising the risks of an escalation that could end in the use of nuclear weapons.

As scholar Pranay Kotasthane has shown, though, India’s armed forces have been underfunded for

years, diminishing their edge over Pakistan. A Pakistan army delegitimised by military defeat might prove even less effective at reining in jihadist infiltration. India might be able to establish a new Line of Control with the same old problems.

There’s a fifth option, the most painful and inconceivable—to do nothing except symbolic diplomatic actions. This is the path Prime Minister Manmohan Singh took after 26/11, after his military chiefs informed him they could not guarantee a decisive victory over Pakistan. The actions so far taken by PM Modi, like diminishing diplomatic ties and placing the Indus Waters Treaty in abeyance, seem to be crafted from much the same template.

A crisis without end?

The scholar R. Rajaraman once described the India-Pakistan contestation as a Three-Body Problem—a term physicists use to describe the extraordinary complexity of determining the motion of three celestial objects moving under no influence other than their mutual gravitation. The motion of three bodies orbiting each other becomes chaotic, and—except in some exceptional cases—no equation can always solve it. Even though Rajaram’s reference was to the impact of China on the course of the India-Pakistan conflict, there are other powerful gravitational influences, too.

Among other things, the Kashmir conflict is shaped by the Pakistan army’s struggle for primacy within the state it rules; the struggle of political forces committed to transforming Pakistan into an Islamic state; and even the unresolved resentments and grief of Partition. Islamabad has learned that it cannot win Kashmir. The purpose of its military is not to win Kashmir or make strategic gains for Pakistan, but to inflict suffering on India. Four wars, each a defeat for Pakistan and an insurgency that has cost tens of thousands of lives, have failed to change this reality.

To restore India’s red lines in Kashmir will need a careful, reflective strategy, not action taken in a spasm of rage.

None of the five choices have worked against Pakistan. India can consider the following steps to cause problems for Pakistan. The real enemy is Pakistan army including ISI and the various terror groups. The Pakistani people are not the enemy. India can start covert operations to assassinate the chiefs and main guys of the various terror groups, top guys of in ISI, the Pakistan army or even the Pakistan government who help the terror groups. Second, India should destroy Pakistani military infrastructure from inside Pakistan through covert operations. Use the die-hard RSS guys for this purpose. Third, India has to work with USA, IMF and World Bank to use FATF to take strict action against Pakistan. Fourth, India should work with Russia to force China stop exporting arms to Pakistan. Last and the fifth, India should strengthen itself by stopping the game of hatred against Indian Muslims as that has made India divided and by stopping Angiveer scheme as that has weakened Indian defense forces.

It appers that Mr Swami went for ground to estabish the loss in Balakot, and IAF capability. He should just for traning exceris with army and IAF then he will know how must destruction take place.

Fighting to restore love and peace in my relationship was incredibly frustrating—until I came across a video of a woman sharing her testimony about how her marriage was restored. It gave me hope for something I never thought was possible. Now, my partner and I are happily reunited, living in love and harmony. I’m truly grateful to Mandla for the help he gave me and my family.

If you’re struggling in your marriage or relationship, don’t give up—there’s still hope. You can reach out:( supremacylovespell01 @ gmail. com).

Its painful and slow and may take 15 years. But start building dams and divert the water to Dehli and Haryana.

That will solve the problem,

I always love your writing since it has an academic tinge to it! Also liked the frank conversation you had with Gen Panag which was thought provoking.

I might add a sixth option – one that achieves its aims without necessarily losing too much of lives – supporting Afghanistan in its pursuit of putting pressure on Pakistan. Much as it is straddled with the same risks of having snakes in our backyard, it would be helpful to at least have a buffer state between us and Afghanistan that is not powerful enough to cause hurt by a thousand cuts.

Airstrikes are ruled out because our jets are ancient and are only a few in number. Ground strikes are useless. Assassination sounds good. Patriots can be recruited to destroy terrorist handlers inside Pakistan including the ISI and also expensive infrastructure to weaken the state.