Despite frequent rhetoric about gender equality, women remain largely invisible in China’s political landscape. While President Xi Jinping’s appearance at the 2025 Global Women’s Summit projected an image of empowerment, the reality within the Chinese Communist Party tells a very different story. At the highest levels of power, women’s representation is almost entirely absent.

It is hardly surprising to see very few women at high-ranking CCP meetings. China’s recently concluded 15th Five-Year Plan session was no exception. Women continue to be underrepresented in the upper echelons of both the CCP and the broader political system.

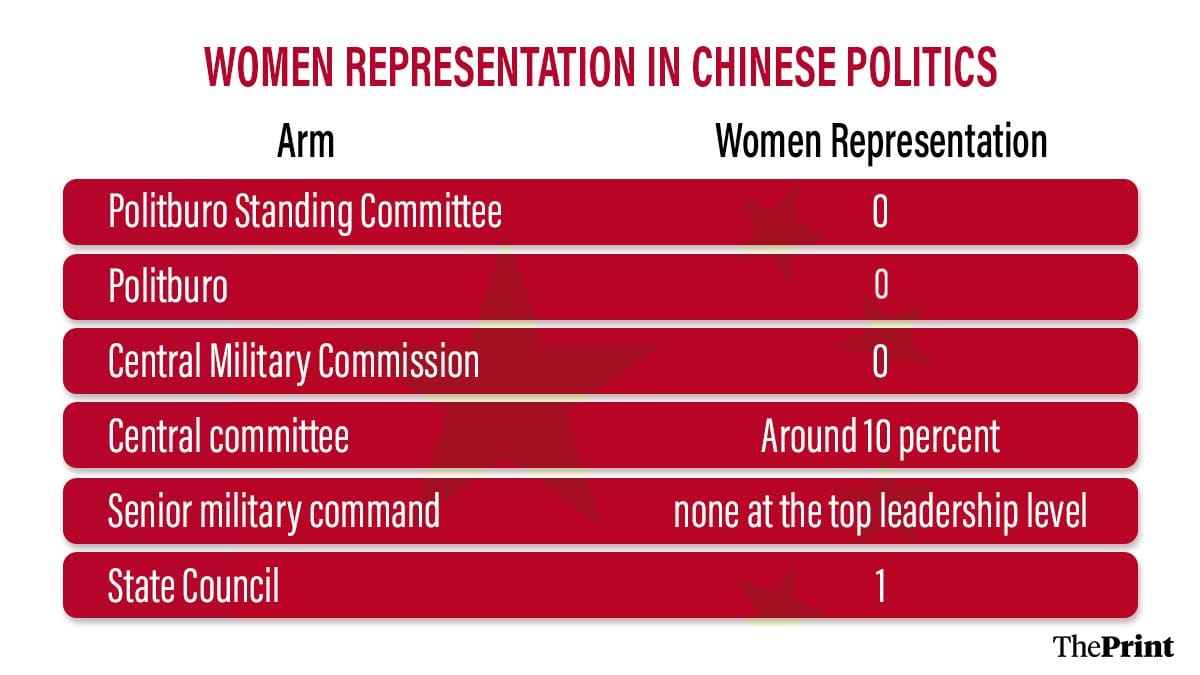

Notably, there is not a single woman among the 24 members of the current Politburo, breaking a two-decade tradition of female representation. No woman has ever served on the Politburo Standing Committee, the CCP’s top decision-making body, since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

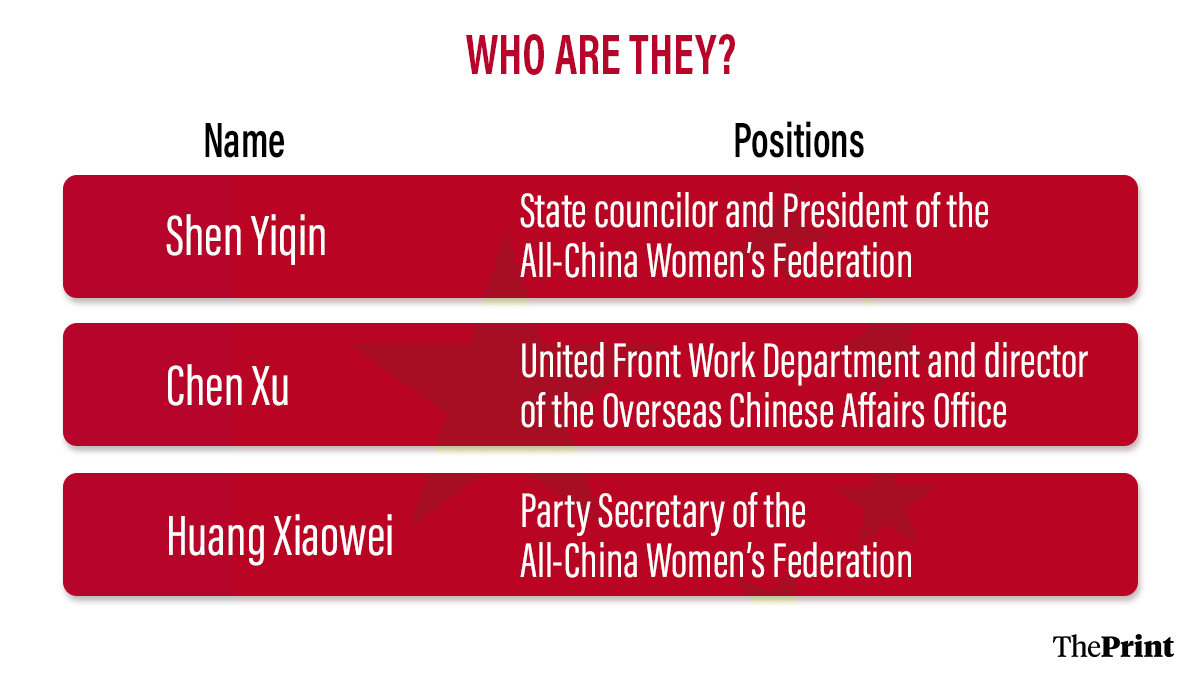

Shen Yiqin, currently holds the highest position held by any female official in the 2022–2027 leadership cycle. She is one of the country’s five state councillors.

The composition of China’s political and military leadership continues to reflect entrenched gender asymmetry, as women seldom occupy positions heading provinces, ministries, or core Party organs that usually pave the way to the Politburo Standing Committee.

Also read: China’s young compare themselves to Nepal’s Gen Z—pragmatic vs street protesters

Women in Chinese diplomacy

Diplomacy appears to fare slightly better, perhaps because diplomats are not true decision-makers within China’s political system. Hua Chunying, now an Assistant Foreign Minister and a member of the Party Committee, long served as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson, a rare example of a woman with sustained public visibility.

The Foreign Ministry appears to be more gender-inclusive than the military or top party bodies, but no female diplomat currently heads major embassies such as those in the United States, Russia, North Korea, India, or Japan. Women often rise through strict protocol, consular, or communications channels rather than through strategic or security portfolios. Figures such as Hua Chunying embody China’s efforts to project a modern, gender-balanced image abroad while maintaining tight control over foreign messaging.

A notable example is Hou Yanqi, former Ambassador to Nepal and now China’s envoy to ASEAN. During her tenure in Kathmandu, she was proactive in influencing Nepal’s domestic political landscape, reflecting Beijing’s slowly growing confidence in deploying female diplomats in politically sensitive roles.

Also read: China countering Trump with narrative swagger. This is what 8 ‘Zhong Caiwen’ editorials say

Feminism in China

Debates about women’s limited representation in Chinese politics often spill into broader discussions about the roots of Chinese feminism. Following Xi’s speech and China’s hosting of the summit, discussions on Weibo about women’s representation and feminism briefly surged. Yet, direct references to political gender inequality were scarce, perhaps due to state censorship or self-censorship.

Some critics argue that feminism in China has been shaped by Western ideology and thus view it with suspicion, while others see it as an integral part of China’s socialist legacy. Dai Jinhua, Professor of Chinese Literature and Cultural Studies at Peking University, observes that contemporary Chinese feminism has become increasingly influenced by foreign NGO funding and Western middle-class theories, which she believes are detached from the lived realities of most Chinese women, especially migrant and working-class women. Though she acknowledges that Chinese law provides formal gender equality, she criticises how feminism in China has become an elite, academic pursuit rather than a social movement.

A popular Weibo post claimed that feminism in China has been “misguided” by Western influence, portraying it as anti-government and anti-male while being overly sympathetic to Western norms. It argued that feminism has undermined traditional gender relations, contributing to declining marriage rates and a weakening of family structures.

In contrast, another widely shared post countered that narrative:

“To claim that all Chinese feminist theory is imported from the West ignores historical reality and undermines the achievements of decades of socialist construction. Chinese feminism is homegrown—rooted in revolutionary struggles, the expansion of women’s education since 1949, their participation in the workforce, and the state’s constitutional commitment to gender equality. As China has risen, so too have its women. To dismiss this as a ‘Western import’ diminishes China’s own ideological and social legacy.”

Also read: China launches K visa amid H-1B row. It is Beijing’s latest move to attract global talent

The persistent gap

At the Global Women’s Summit, Xi declared that women in China truly “hold up half the sky” in economic and social development. While that may hold true at the societal level, women’s presence in the political hierarchy remains fragile.

Ironically, Chinese social media abounds with content about historical female figures such as Feng Ling of the Western Han dynasty—China’s first recorded female diplomat—yet discussions of contemporary female leaders remain rare. Under Xi, the CCP’s political structure has become even more centralised and male-dominated. Power increasingly revolves around a tight inner circle of male loyalists, leaving women further removed from key decision-making networks.

As China continues to assert its global ambitions, the exclusion of women from its political core stands out as one of the sharpest contradictions in the country’s pursuit of modernity and equality.

Sana Hashmi is a fellow at Taiwan Asia Exchange Foundation. She tweets @sanahashmi1. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Comrade Brinda Karat has no problem the men’s club and loves it.