Nalanda, the Buddhist mega-monastery in present-day Bihar, was perhaps the single most famous centre of higher learning in all of Asia. It attracted students from Java, Tibet, China, and possibly even Mongolia and Korea. How did it rise to such eminence? As controversies rage about entrance examinations and higher studies in India today, the past holds some lessons and surprises.

Getting into Nalanda

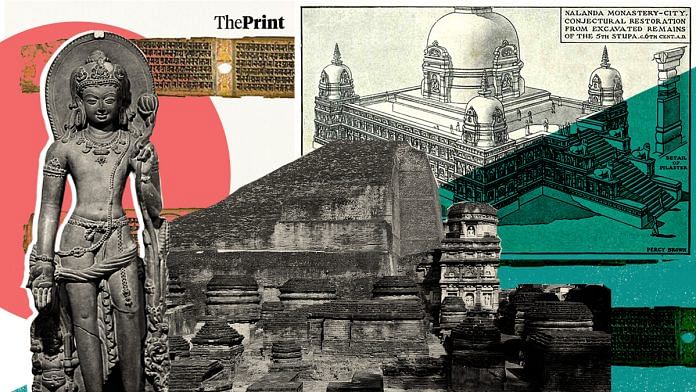

Trekking across deserts, passing through glittering Central Asian cities, and braving hostile mountain passes, the 7th-century Chinese monk Xuanzang arrived at Nalanda. The site has often been described as a university, but in reality, it was a vast complex home to multiple Buddhist monastic orders—a Maha-vihara, or Great Monastery. Xuanzang spent several years studying and collecting texts at Nalanda before returning to China. He left the clearest-surviving account of how Nalanda operated in its heyday, with later disciples and biographers adding many fantastical details.

According to Xuanzang, entering the Great Monastery required clearing an oral examination conducted by its gatekeepers. Historian RK Mookerji, in his monumental study of ancient Indian education, described these gatekeepers as “expert religious controversialists, who were always ready with difficult problems to try the competence of the claimants for admission.” Serious applicants needed a command of Buddhist and Vedic scriptures, commentaries, and logic. Most Nalanda applicants already came from elite backgrounds, equipped with royal or monastic connections that facilitated such knowledge. Even among this erudite pool, Nalanda’s admission rate was about 20 per cent, which is considerably higher than contemporary entrance exams, at least when properly conducted. NEET, for example, has a success rate of 7–8 per cent.

Getting into the Great Monastery was just the beginning. Similar to PhD programmes today, students needed a master to accept them as a disciple. Foreign students at Nalanda were generally there to refine their understanding of complex and esoteric subjects, with much learning conducted through argument and debate. Xuanzang claims there were nearly 10,000 resident disciples and 1,500 masters—about six students per teacher. (Archaeology, however, suggests that only a fraction of this number could actually have lived on the site). In comparison, India’s largest universities today have anywhere between 300,000 and 500,000 students spread across multiple affiliated colleges.

Also read: Kashmiris took Buddhism to the West—when Mongol rulers imported them to Iran

Student life

Nalanda’s low student-to-teacher ratio meant that most studies were conducted through memorisation, discussion, and argument rather than lectures and notes. There were no “semesters” or “grades,” just a rigorous daily eight-hour schedule. Time was kept by water clocks and announced through drums and conch-shells. Students had to take ritual baths and assist in religious ceremonies. Discipline was no laughing matter at Nalanda; even eating outside designated hours could result in expulsion. It was a monastery first and a university second.

Nalanda’s monastic orders were fabulously wealthy, and they knew how to market themselves. They took great care of foreign students, understanding that they would evangelise Nalanda in distant courts. Xuanzang, for example, was welcomed by hundreds of priests carrying standards, flowers, and perfumes, and escorted to Shilabhadra, the senior-most monk at Nalanda. Shilabhadra took Xuanzang as his personal disciple, granting him a daily ration of nutmeg, areca-nut, camphor, rice, and butter. Xuanzang was even allowed to ride an elephant.

Other foreign visitors received similar honours, but most Nalanda disciples did not—despite its wealth. In fact, another Chinese visitor, Yijing, hints obliquely that some granaries were overflowing to the point of rotting, that some monasteries did not admit strangers, and that others did not even feed their own students. Most monks who died at Nalanda gave their meagre possessions to their monastic order. However, the senior-most monks commanded vast properties, were respected by royalty, and lived well.

Also read: How a fading Benares dynasty commissioned North India’s greatest Ramayana paintings

Nalanda’s purpose

For many centuries, Nalanda attracted the brightest minds in northern India and beyond, equipping them with knowledge and skills to work as ritual masters and preceptors in other courts and monasteries. But for all of its achievements, it was not a “university” in the modern sense. Much of its curriculum focused on sacred texts, both Buddhist and Vedic. While it conducted research in linguistics, mathematics, philosophy, astrology, and ritual, its masters and disciples did not recognise “science” as a separate discipline. To them, developing complex rituals based on rigorous metaphysical reasoning was more likely to ensure prosperity than investigating and harnessing natural principles.

What explains the success of Nalanda? It was closely allied to the ruling classes of the Gangetic Plains, developing skills and practices useful to medieval royals. Patronising Nalanda brought religious merit and ensured the development of complex ritual knowledge. Rituals, to the medieval mind, could ensure rainfall, good health, successful marriages, and even military victories. As a result, Nalanda’s component monasteries received patronage from royals, ministers, and officials; they owned villages and collected rent.

Also read: What do a Hindu king and a Muslim sultan have in common? Both looted Kashmir’s temples

Nalanda’s decline

There is little doubt that Nalanda’s wealth made it a target for Turkic raiders in the 12th century, though it survived for a few decades after. But the fact is that it was already in decline by the time. By the 11th century, Nalanda and other Buddhist monasteries were losing importance in eastern India. Indonesian and Javanese masters had become pre-eminent . Meanwhile, the rulers of present-day Bengal and Bihar found that Brahmin settlements were more useful than Buddhist monasteries.

This trend wasn’t unique to eastern India. Across South Asia in the 11th century, royal patronage shifted from concentrated Buddhist centres to dispersed Brahmin settlements to control the countryside. Buddhists and Brahmins both knew how to manage and administer properties. But Buddhists applied this knowledge to their own monasteries, while Brahmins did so for kings as well.

In 1020, for example, the Chola emperor Rajendra I (1012–1044) gave land to 1,080 Brahmin families, praising them as “unequalled in courage, stability, penance, greatness and humility.” Not coincidentally, many of Rajendra’s senior officials were Brahmins. One of them, Krishnan Raman, worked as a general and chief secretary. Historian Y Subbarayalu, in South India Under the Cholas, notes that three of Raman’s sons and one of his grandsons also worked as senior Chola officials.

Rather drily, Subbarayalu notes that “nepotism played a not insignificant role in the recruitment for Chola officialdom.” At its peak in the 11th century, the Chola state was perhaps the mightiest in the subcontinent, routinely fielding thousands of warriors, collecting tens of thousands of tonnes of rice, and building enormous temples. This situation did not last forever. By the 12th century, according to Subbarayalu, elite officials had collected enormous properties and stopped paying taxes, driving the Cholas into crisis.

Medieval India’s education and bureaucratic systems weren’t perfect. Much depended on the whims of the state and good marketing, while the wealthiest members of the system were rarely held accountable. Paradoxically, these factors created remarkable institutions like Nalanda and the Chola officialdom, but also led to their ultimate undoing. The achievements of Nalanda are well worth striving for—but only if we do not repeat its flaws and failures.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)