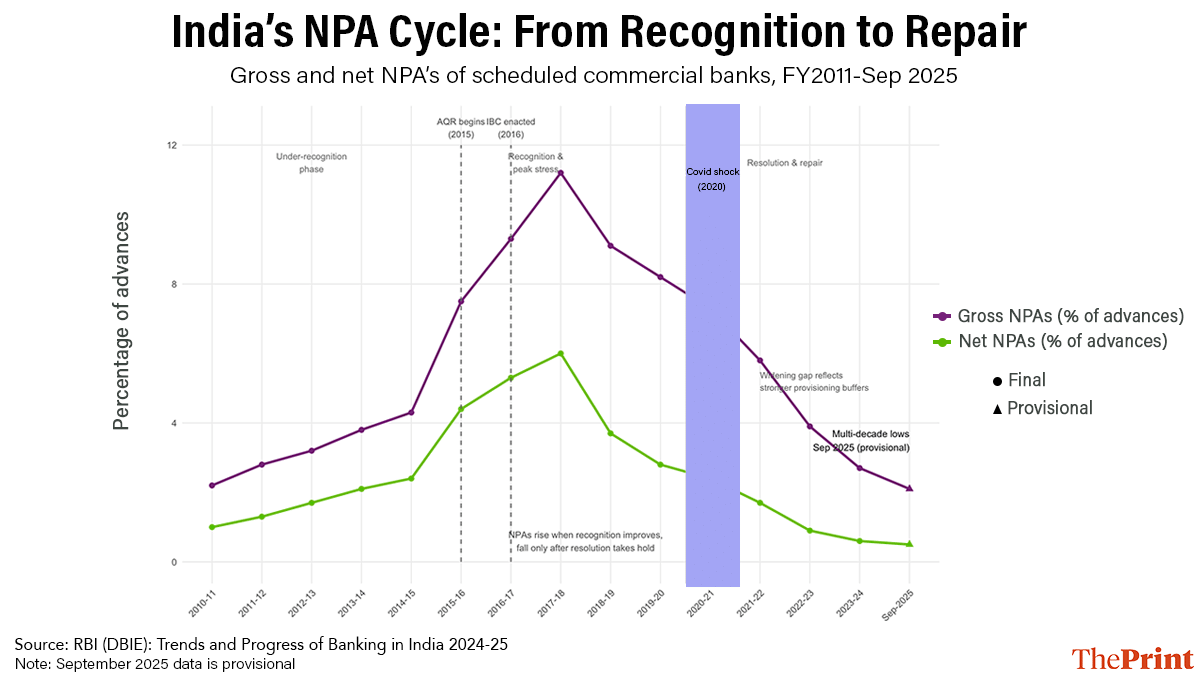

The Reserve Bank of India’s recent release of banking data, which landed quietly just before the year’s end, carries significant implications. According to the RBI’s Report on Trend and Progress of Banking In India 2024-25, the gross non-performing assets (GNPAs) of scheduled commercial banks decreased to 2.1 per cent by 30 September 2025, while net NPAs declined to approximately 0.5 per cent.

These figures represent multi-decade lows, levels not observed since prior to the last credit cycle’s downturn. For a system that has spent much of the past decade battling stressed balance sheets, this development signifies a decisive departure from previous trends.

However, this headline improvement merely initiates the narrative. To ascertain whether this represents a transient moment of relief or a sustainable structural transformation, the data must be interpreted not as a static snapshot, but as a trajectory — one that charts the historical progression of India’s banks and identifies the potential risks that remain.

From crisis to cleanup

The long-term trajectory in gross and net non-performing assets (NPAs) provides a crucial overview of the financial landscape. The marked increase in non-performing loans during the late 2010s signifies the unwinding of a prior credit expansion, particularly in the sectors of infrastructure and corporate lending. What followed was characterised not by rapid resolution but by a slow and arduous process of recovery, involving asset quality reviews, regulatory interventions, recapitalisation efforts, and extensive balance-sheet rehabilitation.

The gradual decline that followed, culminating in today’s low Gross NPA (GNPA) and Net NPA (NNPA) ratios, is noteworthy, precisely due to its incremental nature. Visually, the data illustrates a financial system that did not sprint to stability but rather progressed slowly, absorbing losses incrementally. Of particular significance is the expanding disparity between gross and net NPAs over time. This gap reflects enhanced provisioning buffers, which suggests that banks are now more proactive in recognising risks and are now allocating capital accordingly, rather than postponing the acknowledgment of losses. This transition from a state of denial to one of discipline is what distinguishes the present recovery from previous, less sustainable recoveries.

Nevertheless, the presence of low headline NPAs often invites scepticism, and justifiably so. The key question that remains is whether these non-performing loans have been genuinely resolved or merely pushed out of sight, a distinction that cannot be conclusively determined by aggregate figures alone.

Why this recovery is different

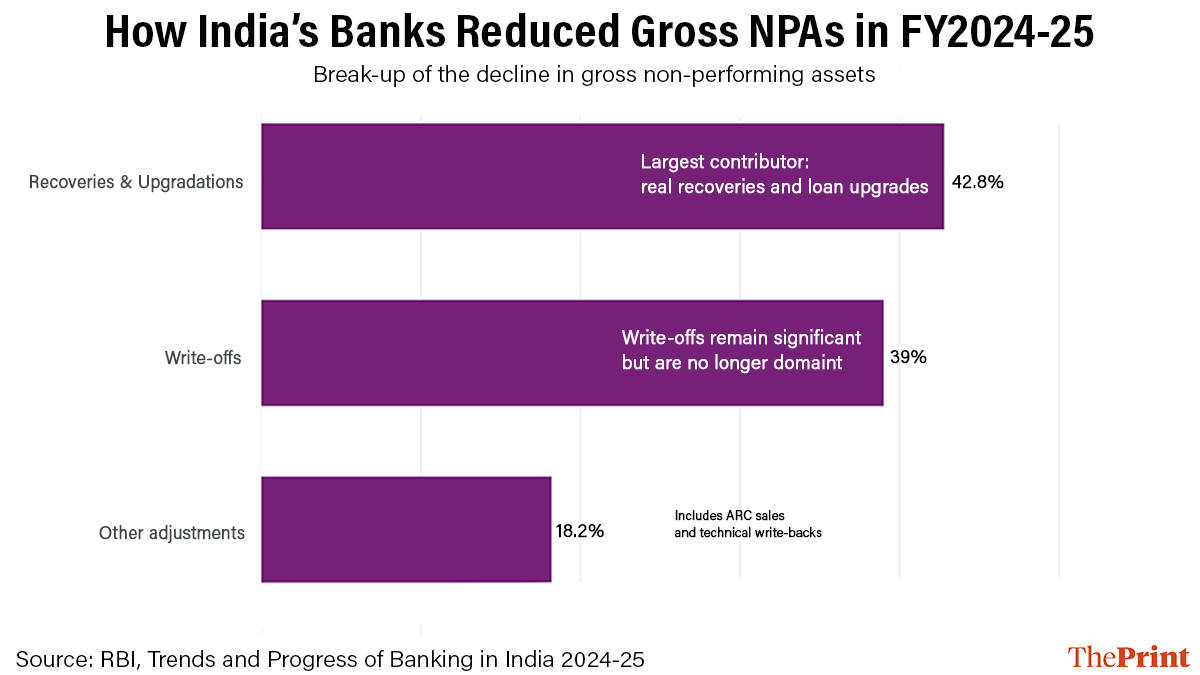

The RBI’s disaggregated data provides a notably clear insight. In the fiscal year 2024-25, approximately 42.8 per cent of the reduction in gross NPAs was attributed to recoveries and upgrades, rather than write-offs. This indicates that a substantial portion of stressed loans was reclassified as ‘performing’ due to borrowers enhancing their repayment capabilities. This distinction is crucial, as it differentiates between merely cleaning a balance sheet and addressing the root cause of the problem.

This differentiation is significant. While write-offs may clean up bank records, they do not rectify the underlying economic issues. In contrast, recoveries and upgrades indicate that projects are becoming viable, cash flows are stabilising, and resolution mechanisms are effectively functioning. Essentially, the data illustrates a reduction in bad loans due to the return of funds, rather than the concealment of issues. In this context, the decline in NPAs reflects not only accounting prudence but also improved borrower health, signifying that economic recovery has positively impacted bank balance sheets.

However, addressing past financial stress is only part of the challenge. The more difficult task is ensuring that current lending practices do not evolve into future problems. This challenge is most evident in a particular forward-looking metric.

Also read: Beyond electricity and exports—how should India actually check GDP growth now?

The real signal lies in fresh stress

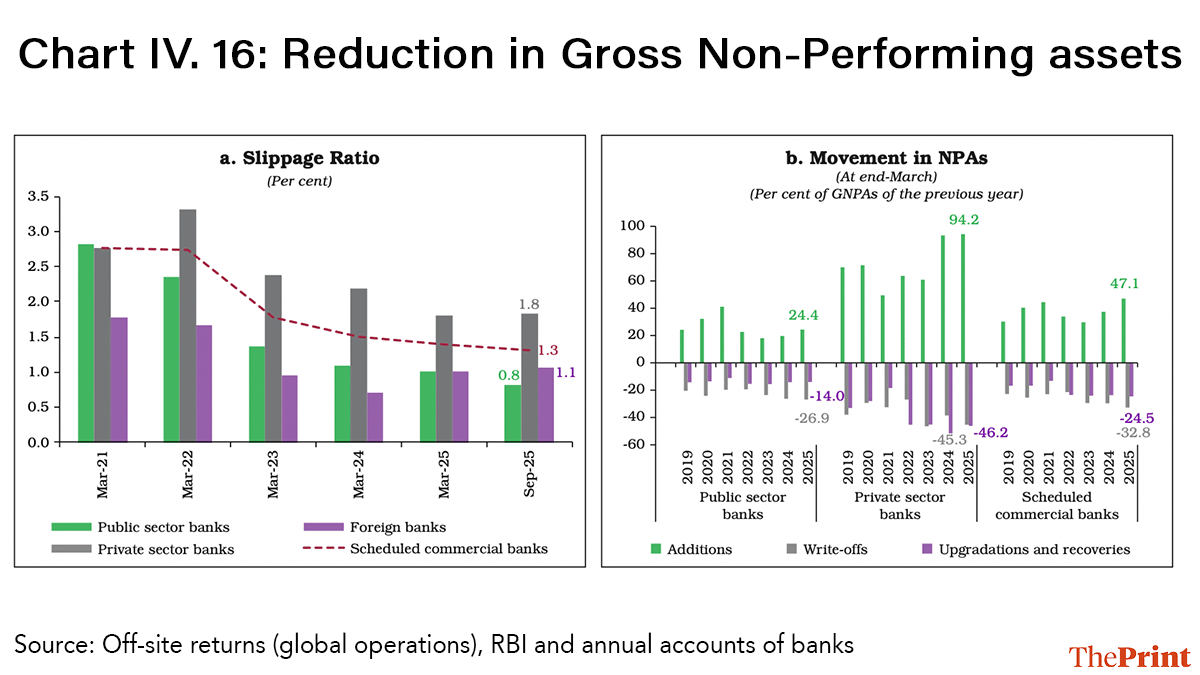

If NPAs tell us about the past, slippage ratios tell us about the future. Notably, the slippage ratio, which represents the proportion of standard loans that become non-performing within a year, has decreased for the fifth consecutive year, reaching approximately 1.4 per cent by March 2025, according to RBI data. This positive development has occurred alongside an acceleration in overall credit growth.

The concurrent decline in slippages and expansion in credit is significant, as it indicates enhanced underwriting standards and more prudent risk pricing. Both public sector banks and private sector banks have reported reduced new slippages, although private banks continue to exhibit relatively higher ratios, reflecting their greater exposure to unsecured retail lending.

Collectively, these trends suggest a structural improvement in credit discipline. Banks are not merely addressing inherited financial stress but also actively mitigating the accumulation of new stress on a large scale. And yet, precisely at this juncture in the credit cycle, when confidence is restored, that risks are prone to reemerge.

Data carries a warning

Historical evidence shows that banking systems seldom collapse when stress is obvious; rather, they fail when confidence returns too quickly. Robust balance sheets, increasing profitability, and declining NPAs create incentives to pursue growth, relax standards, and engage in aggressive competition for market share. The risks created during such periods often become apparent only years later, long after the initial optimism has dissipated.

Early indications of this tension are already observable. Although overall asset quality has improved, stress remains uneven across segments, with unsecured retail credit exhibiting greater vulnerability than traditional housing or education loans. While none of these factors are alarming in isolation, collectively they emphasise a well-known lesson: low NPAs do not equate to low risk. The current challenge is not recovery, but restraint. Stress testing, dynamic provisioning, and meticulous monitoring of rapidly expanding loan categories will be significantly more important than celebratory narratives. The credibility of India’s banking recovery hinges on whether discipline is maintained when it is least politically and commercially convenient.

India’s banks are in a healthier state than they have been in decades, as evidenced by the data. However, this same data also carries a warning. The last instance when optimism outpaced prudence resulted in a decade-long repercussion of the system. The sustainability of this recovery will depend not on the current appearance of clean balance sheets, but on how carefully banks conduct themselves now that they are in a position to be confident.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

Very insightful, Bidisha.

Is additional or more granular data not available? It would be great if you could analyze and identify which industries are finally repaying their overdue loans (otherwise identified as NPAs). And who owns the companies among them with the larger borrowings.

I need to confess that I am very poorly educated in matters of finance and economics (as also in others). I struggle to grasp even basic jargon presumably common in the field. You would be doing guys like me a great favour by narrating your analysis to a greater extent at our level, i.e., by dumbing down or explaining the material further, wherever possible. For example, I am unable to comprehend the distinction between gross NPAs and net NPAs, both of which are expressesd as a percentage of “advances” (?).

Regardless, I think I have learned a bit. It is a miracle. Thank you.