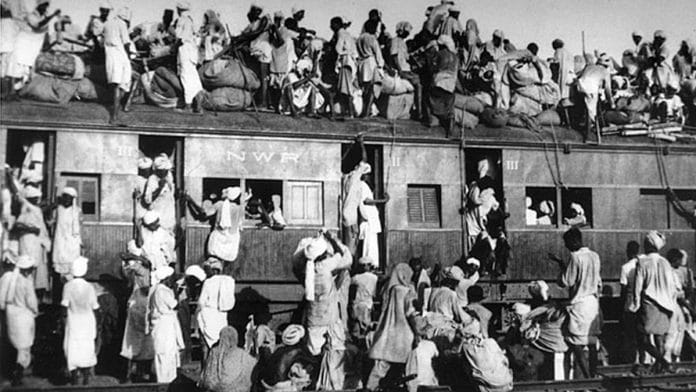

New Delhi: Since 2021, the Government of India has systematically institutionalised the Partition Horror Remembrance Day, with the establishment of academic positions, revised syllabi, and grand advertisements and exhibitions to entrench this commemoration in public consciousness. While remembering the traumatic Partition of the subcontinent—which left millions dead and displaced—appears noble, its institutionalisation raises profound ethical questions about how societies should engage with historical trauma.

The horrible massacres of 1947 represent one of history’s great tragedies, affecting not only those who suffered directly but also those who struggled desperately to prevent it. Commemorating such trauma can serve legitimate purposes: Honouring the dead and extracting lessons to prevent future violence. Yet the haunting words of Auschwitz survivor and writer Primo Levi echo with particular resonance: “It has happened. It can happen again.” Levi understood that the imperative to bear witness to trauma sits uneasily with the instrumentalisation of trauma for political purposes.

Memory, as scholars have long established, operates on multiple levels. Individual or family memories—personal recollections of lived experience—typically fade within a generation or two. Social memories, what Maurice Halbwachs termed recollections shaped by intimate frameworks of family, neighbourhood, and shared community experience, persist longer but remain bounded by specific groups. Cultural memory, as scholars have demonstrated, represents something altogether different in texture and function—institutionalised through rituals, monuments, and state-sponsored commemorations, it can endure for centuries and shape entire civilisations.

For decades, memories of the tragedies of Partition remained largely within the first two categories: stories passed down through generations of survivors, documented by literary historians, carried in the bodies and dreams of those who experienced displacement and loss. These memories bore the authenticity of lived experience and the intimacy of family transmission. As the generations of direct witnesses pass away, these personal and social memories are now increasingly being transformed into cultural memory.

This transition from lived memory to institutionalised memory, however, is neither neutral nor inevitable. It reflects deliberate political choices about which aspects of the past to remember, how to frame historical events, and—most crucially—whose contemporary interests they should serve. The fundamental question is not whether Partition horrors should be remembered; the suffering was real, the trauma profound, and the historical lessons vital. Rather, we must ask what kind of memory serves humanity’s broader interests and what kind serves narrow and divisive political projects.

Also read: Nehru and Jinnah made Indian politics their personal quarrel. Partition was a consequence

Memory in service of power

Levi, the Italian survivor of Auschwitz, understood that suffering, while deserving witness and acknowledgement, does not automatically grant moral authority or justify future actions. Memory that organises itself primarily around victimhood risks becoming memory that culminates in revenge. The proliferation of memory media, i.e., museums, digital archives, etc., has dramatically intensified these risks. Digital platforms, for example, flood the online universe with recurring images and narratives, reducing complex historical events to easily shareable content. While such democratisation of memory has helped amplify marginalised voices, it also enables the decontextualisation and instrumentalisation of historical suffering.

A Bengali refugee’s story of displacement can become viral content that shapes the political consciousness of urban middle-class Indians who have never directly experienced such trauma. The efforts through digital platforms to reframe historical traumas as evidence of an enduring social divide based on religion may find the Partition massacres as its most credible justification. This is at the cost of viewing the massacre as the tragic consequence of colonial abdication and deliberate communal manipulation. Such framing ends up serving the present-day exclusionary politics while denying the complex lessons that Partition’s history offers—about the fragility of coexistence and the responsibilities of ethical governance.

One can remember the Partition horrors differently—ethically. This alternative invites one to share responsibility for each other’s sufferings instead of invoking competitive victimhood. This demands remembering Partition not as “our” trauma versus “theirs,” but as a collective failure of ethical imagination that devastated all communities. Such ethical remembrance would pose different questions: How did neighbours transform into enemies? What role did local power structures play in inciting or preventing violence? How can institutions be constructed to prevent such breakdowns of civility?

The institutionalisation of Partition memory through official commemorations is not inherently problematic. The critical question concerns what social and political frames are presented and what social and political vision they offer. Only an ethical commemoration will allow the intellectual courage required to examine how ordinary people became participants in extraordinary violence: Then and now.

The choice before us, therefore, is also historically given: Memory in service of humanity or memory in service of power. The survivors of Partition, and the millions who died, deserve better than having their trauma instrumentalised for contemporary political projects. They deserve remembrances that learn from their suffering rather than perpetuating it. Only such commemoration demands moral commitment to build institutions and civic culture capable of preventing descent into barbaric massacres.

Rakesh Batabyal teaches Media history at JNU and has written extensively on the Partition. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Sometimes I wonder whether these so called intellectuals so deep in their subject that they forget the other dimensions or aspects of any issue or for that matter a rememberance like partitions horrors. They forget that this is not a utopian world but a world where things can happen again as the author quoted. A person who has suffered can not be given a moral lecture of ethics when they recall their miseries. The person here a country will not need a moral lecture when it is mourning. Since these things can happen again we need to remind our population and recognise the events precursor to the horrors. The history needs to be taught so that people are able to recognise the events and stop it before it spreads. They need to remember that it started on the day when the Muslim league and its backers and followers went on rampage on the direct action day. They need to remember that voices like the Muslim league are raising again and the people need to recognise it and they need to nip it in the bud so that they don’t have to see the horrors that our people had to see during partition of 1947. There is no ethics in suffering so they author can take their ethical lecture somewhere else

No wonder Mr. Rakesh Batabyal teaches at JNU.

He. and others of his ilk, has never voiced concerns about the violence unleashed on Bengali Hindus in Bangladesh ever since Md. Yunus assumed power after Sheikh Hasina’s exit. The gangrapes and abductions and forced conversions of Hindu women, murders of Hindu men and destruction of Hindu owned property does not bother them at all.

But a Bengali Hindu’s remembrance of the Partition horrors upsets them.

Very very thought provoking writeup. Reminds me of the time when the public intellectuals were the true keeper of our public conscience and were one of the great pillars of our civic society.

( Unlike the present R.W.A)

if the victim was Muslim it was remember to shame Hindus . now don’t cry.