Last June, the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, Yale University and The BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal) started a new “preprint server” for medical research called MedRxiv. Preprint is one term of art for an academic paper that hasn’t been peer reviewed or published yet. Working paper is another. They’ve been distributed at meetings and seminars as long as anyone can remember. In 1991, physicists began sharing theirs on the internet on a server that came to be called ArXiv (pronounced “archive”). Mathematicians, astronomers, economists and scholars in a few other disciplines soon followed suit — some on ArXiv, some on other sites.

Medical researchers did not. For one thing, peer-reviewed biomedical journals publish research findings faster than those in some other fields (average time to publication is half what it is in business and economics), so the need for a speedy alternative was less pronounced. For another, medical research often involves questions of life or death that presumably deserve more pre-publication scrutiny than, say, a theoretical physics paper. And given that publishing in prestigious journals is key to career advancement, and prestigious medical journals have long made a big deal about having exclusives on new research results, researchers had legitimate worries that releasing results earlier could hurt them.

Things started off unsurprisingly slowly for MedRxiv last summer, and there wasn’t all that much sign of an acceleration over the course of 2019. Then a new coronavirus began infecting people in Wuhan, China, and, well, you can probably guess what happened next:

Page views to the MedRxiv site are now averaging 15 million a month, up from 1 million before the pandemic. Something significant has changed in medical research.

Many of the coronavirus-related papers being posted on MedRxiv are rushed and flawed, and some are terrible. But a lot report serious research findings, some of which will eventually find their way into prestigious journals, which have been softening their stance on previously released research. (“We encourage posting to preprint servers as a way to share information immediately,” emails Jennifer Zeis, director of communications at the New England Journal of Medicine.) In the meantime, the research is out there, being commented on and followed up on by other scientists, and reported on in the news media. The journals, which normally keep their content behind steep paywalls, are also offering coronavirus articles outside of it. New efforts to sort through the resulting bounty of available research are emerging, from a group of Johns Hopkins University scholars sifting manually through new Covid-19 papers to a 59,000-article machine-readable data set, requested by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and enabled by an assortment of tech corporations and academic and philanthropic organizations, that is meant to be mined for insights using artificial intelligence and other such means.

This is the future for scientific communication that has been predicted since the spread of the internet began to enable it in the early 1990s (and to some extent long before then), yet proved slow and fitful in its arrival. It involves more or less open access to scientific research and data, and a more-open review process with a much wider range of potential peers than the peer review offered by journals. For its most enthusiastic boosters, it is also an opportunity to break through disciplinary barriers, broaden and improve the standards for research success and generally just make science work better. To skeptics, it means abandoning high standards and a viable economic model for research publishing in favor of a chaotic, uncertain new approach.

Also read: Researchers say vaccine for Covid-19 could be ready in a year, to look for ‘signal’ in June

I’m mostly on the side of the boosters here, but have learned during five years of writing on and off about academic publishing that the existing way of doing things is quite well entrenched, and that would-be innovators often misunderstand the challenges involved in displacing or replacing it. This moment does feel different, though. “It’s going to really be fascinating to see if this will be the tipping point,” says Heather Joseph, executive director of the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, an organization of academic libraries that has been pushing hard for a more open research infrastructure. “Because of the way distribution of scientific information is being piloted in a new way in the Covid crisis, my hope is that this will spill over to other areas in subsequent years,” adds Ijad Madisch, a German virologist who is founder and chief executive of ResearchGate, a social network for researchers that has seen a surge in activity and collaboration around Covid-19. “It scares me that we as scientists might just go back to doing things as we did before.”

A ‘Scoop-Protection Device’

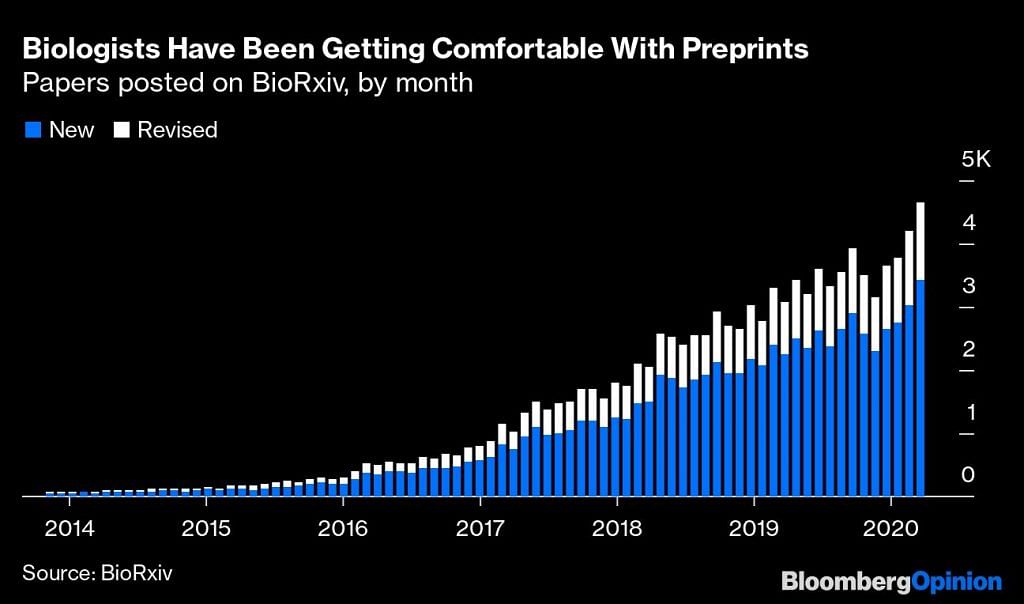

At MedRxiv, co-founder Richard Sever is pretty sure that medical researchers won’t be turning away from preprints after the crisis has passed. “Once a field starts doing this, they don’t stop,” he says. Sever is assistant director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press and also co-founder of BioRxiv, MedRxiv’s sister preprint server, which he has watched catch on with one biology subfield after another (first genomics, then cell biology, most recently neuroscience) since its founding in 2013. BioRxiv has also seen a recent surge in submissions and readership, albeit less dramatic than MedRxiv’s given that it was starting from a much larger base.

A big part of the attraction of preprints for researchers studying a fast-moving phenomenon such as Covid-19 is that they rather than journal editors control the timing of the release of new research results. “It’s a scoop-protection device,” Sever says. Other major destinations for coronavirus-related preprints include Research Square, Preprints.org and the Center for Open Science’s OSF Preprints. Overall, there were at least 8,830 biomedical preprints posted in March, up 142% from March 2019, according to data compiled by Jessica Polka and Naomi Penfold of the nonprofit Accelerating Science and Publication in Biology (aka ASAPbio).

BioRxiv and MedRxiv don’t accept every submission. Pure opinion pieces aren’t allowed — there has to be actual research involved. Beyond that, says Sever, “if something goes up on BioRxiv it just means we don’t think it’s dangerous and it’s probably not crazy nonsense,” while for MedRxiv there’s heightened scrutiny of potentially dangerous claims plus a checklist of conditions that any clinical research paper must satisfy. Both servers also recently began declining papers that pointed to treatments for the coronavirus based purely on computer modeling. “We decided that somewhere on this spectrum was a point where peer review was needed,” Sever says.

Also read: Countries pledge billions for vaccine, Middle East eases lockdown & other global Covid news

This came as something of a shock to Albert-László Barabási, a prominent network scientist at Northeastern University in Boston who had a paper on a “Network Medicine Framework for Identifying Drug Repurposing Opportunities” rejected last month by BioRxiv. He eventually just posted it on ArXiv instead, but wondered on Twitter if it might make more sense for BioRxiv to create a scientists-only list for potentially sensitive Covid-19 research. ResearchGate’s Madisch also likes the idea of a setup “where the research community can give feedback before it’s released to the public,” but Sever said he worries that such an approach would just end up favoring an in-crowd of scientists at top universities.

So for now, at least, it’s all happening in public. One oft-heard complaint is that this allows unvetted research to be distributed to lay readers — as with the paper posted on BioRxiv in late January that found an “uncanny similarity” between several genetic sequences in the new coronavirus and those in the human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS, findings that as BuzzFeed News science reporter Stephanie M. Lee described in an account of the paper’s rise and fall were immediately latched onto online as evidence that the virus was man-made. After other researchers tweeted criticism that the findings were in fact probably the product of random chance, though, the authors retracted the paper.

Clearly, preprint servers can allow bad information to be presented to the public. But research findings published in peer-reviewed journals have to be retracted sometimes, too, and many more turn out to be wrong in the sense that they can’t be replicated by subsequent studies. As Stanford Medical School’s John Ioaniddis argued in a 2005 paper so famous that it has its own Wikipedia page, “most published research findings are false.”

That brings us to perhaps the most vigorously debated MedRxiv paper so far, “COVID-19 Antibody Seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California,” posted on the site April 17 by a multidisciplinary team of authors that included Ioaniddis. The paper reported the results of testing for coronavirus antibodies among 3,300 county residents recruited by Facebook ads, 1.5% of whom tested positive. The authors then made a number of statistical adjustments that upped their estimate of the percentage of county residents who had been infected with the coronavirus to 2.49% to 4.16%, which was 50 to 80 times the number of confirmed cases at the time and implied a Covid-19 fatality rate of just 0.12 to 0.2% — not all that different from the rates usually reported for seasonal influenza (although the actual ratio of influenza fatalities to infections is probably lower).

Some infectious disease experts, whose estimates of Covid-19’s infection fatality rate have mostly centered on a range of about 0.5% to 1%, took to Twitter to offer skeptical but reasonably polite critiques. (Disclosure: so did I.) But physicist-turned-virus-researcher Richard Neher of the University of Basel and statistics professors Will Fithian of University of California at Berkeley and Andrew Gelman of Columbia University all argued that the statistical adjustments in the paper were outright wrong, with Gelman concluding on his blog that the authors of the paper “owe us all an apology. We wasted time and effort discussing this paper whose main selling point was some numbers that were essentially the product of a statistical error.”

No such apology has been forthcoming, but the authors did on Thursday replace the paper on MedRxiv with a revised version that changed their estimate of the percentage of county residents infected with the virus to a range of 1.3% to 4.7%, and generally did much more to show their work and stress the uncertainty inherent in their findings. They also expressed appreciation for the many criticisms the paper had received, concluding that, “We feel that our experience offers a great example on how preprints can be an excellent way of providing massive crowdsourcing of helpful comments and constructive feedback by the wider scientific community in real time for timely and important issues.”

Other scientists weren’t so sure the rough-and-tumble — and public — discussion around the paper was such a good thing. Two prominent medical school professors wrote an opinion piece for the science news site Stat decrying some of the criticisms as “ad hominem,” while Neeraj Sood of the University of Southern California, lead author of a related study in Los Angeles County that hasn’t been released as a preprint although preliminary results have been shared, told BuzzFeed’s Lee that “I don’t want ‘crowd peer review’ or whatever you want to call it. It’s just too burdensome and I’d rather have a more formal peer review process.”

But is a more formal peer review really better? “To me there’s no doubt that more eyes on something mean that ultimately a better judgment can be made,” says MedRxiv’s Sever, a molecular biologist with long experience in editing scientific journals.

Journals send articles to two or three people, ask for comments in two weeks, and the reviewers never do it on time and you have to pester them. The chance you get a representative sample is not that great. Wouldn’t it be great if there were a lot of other discussions that had already happened that journals could incorporate in their evaluation?

Also read: Study shows you are 4 times more likely to catch coronavirus indoors than outside

Who’s Going to Pay for All of This?

This implies a world in which open research-distribution channels and peer-reviewed journals exist side by side, playing different roles — which is how things have worked for quite a while in some academic disciplines. “In the old days, journals were viewed as a means of disseminating ideas,” Yale economist Pinelopi Goldberg, then the editor in chief of the American Economic Review, said at a conference I attended four years ago. “The most important function that journals have these days is the certification of quality.” Or as the saying supposedly goes (according to Sever), “Nobody ever got a job by putting something on ArXiv.”

Academic journal publishing is dominated by a handful of for-profit publishers — the largest is Elsevier, a subsidiary of London-based RELX Plc — who sell digital access to their journals in large bundles to university libraries. Medical publishing is a bit different, with many leading journals controlled by nonprofit medical societies and distributed widely among practitioners, but they too rely heavily on subscription paywalls. Keeping scientific research that is funded by philanthropies, universities and government agencies behind such paywalls has been unpopular for a while, and has been coming under increasing pressure from those who pay for the research, especially in the European Union. Publishers and universities have been exploring new “read and publish” contracts in which universities pay both for access to the journals and paywall-free publication of articles by their faculty, but as the consequences of the coronavirus hammer budgets, sharp cutbacks in library spending on journals seem inevitable. “Those kinds of reckonings are coming very quickly,” says Joseph.

Then again, these reckonings could endanger newer forms of scientific communication as well. Although preprint servers don’t cost nearly as much to run as academic journals — ArXiv has expenses of about $2.7 million a year, while the American Association for the Advancement of Science, publisher of the interdisciplinary journal Science, reports journal-and-publishing-related expenses for 2018 of more than $45 million — most have to rely on the generosity of philanthropists and universities to pay the bills, and will struggle to make ends meet in a time of higher-education cutbacks. As scientific-publishing veteran Kent Anderson wrote in his subscription newsletter last week:

Open science, which is essentially a basket of new expenses with no established funding models, isn’t going to suddenly receive millions or billions from the EU or some consortia of universities. So, hit the “pause” button here.

One can imagine the pause button being hit for many aspects of scientific research in the coming months and years. There surely won’t be a shortage of funding for those who study viruses, pandemics and the like, but many other fields could face tough times. In some disciplines this may push scholars toward more open, collaborative ways of doing research and communicating it; in others it may reduce experimentation and communication. The scientific community is not a monolith. But on the whole, it does seem to be moving in a new direction. -Bloomberg

Also read: Good science takes time. Finding a coronavirus miracle isn’t a job for social scientists