Nearly a century ago the notion that ideology could triumph over nature was formulated by the Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko. Lysenko claimed that he could alter seeds to make them immune to the vagaries of nature, in effect growing fruits in the sub-zero terrain of Siberia. Eager to revolutionise agriculture in the USSR, Joseph Stalin put Lysenko at the helm. Lysenko’s radical ideas along with a policy of forcing millions into state-run farms led to disastrous harvests and famine. When Lysenko’s ideas ran counter to the principles of genetics, which was a fledgling field of research in the 1930s, he rubbished science. Despite Lysenko’s failures, Stalin backed Russia’s star scientist because the latter had promised to boost crop yields nationwide and transform the barren Russian hinterland into giant farms. The People’s Republic under Mao Zedong later adopted his methods in the late 1950s and endured even bigger famines. With the passage of time, Lysenkoism entered the lexicon symbolising calculated distortion of facts or theories to favour a political narrative.

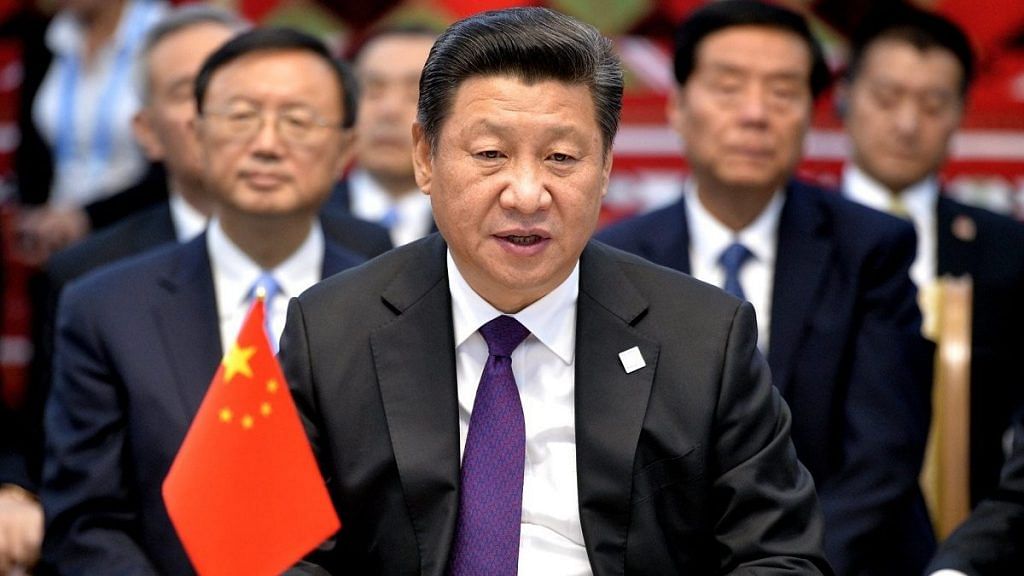

While Lysenko’s birthplace has no use for his ideas today, Lysenkoism seems to live on at least in spirit in the People’s Republic. This can be evidenced by the manner in which China is grappling to tackle the recent COVID-19 outbreak. On 10 May, Shanghai and Beijing—its financial and political capitals—tightened restrictions. Shanghai—China’s most populous city—which is in lockdown mode since March-end is under the global spotlight. This has led to increasing pressure on the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from many quarters to rethink its COVID-19 treatment policies. CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping indicated in early May that there won’t be any dilution of China’s COVID-19 containment approach. He has reasoned that any relaxation of control and prevention measures would overwhelm the healthcare system on account of China’s large number of elderly people and unbalanced regional development.

The People’s Republic under Mao Zedong later adopted his methods in the late 1950s and endured even bigger famines. With the passage of time, Lysenkoism entered the lexicon symbolising calculated distortion of facts or theories to favour a political narrative.

A medical study published on 10 May by researchers from Shanghai’s Fudan University and Indiana University in the US has largely reinforced Xi’s apprehensions. The research warns that removing COVIDi restrictions could lead to the infection of more than 112 million, causing 1.5 million deaths. It estimates that unvaccinated people in China above the age of 60 years could account for nearly 75 percent of the deaths since as many as 52 million in this segment had not been fully vaccinated as of mid-March.

Also read: China’s draconian lockdown measures mobilising popular discontent

Political Lysenkoism colours vaccine plan

To start with, China chose to vaccinate its youth perhaps in the belief that an immunised working-age segment would kickstart the economy. Besides, following the one-child policy for years has left China with a large ageing population, which in economic terms was not very productive and, thus, left out of the calculations. For example, while nearly 90 percent of Shanghai’s 25 million population were covered by vaccines, the corresponding figure in the above 60 years age bracket was 62 percent. Thus, political Lysenkoism at the heart of China’s vaccination strategy has left many elderly unvaccinated, circumscribing moves to relax restrictions. In its eagerness to harvest demographic dividend, China’s approach to vaccination seems to have created a self-perpetuating loop, which is harming the youth.

The fallout from lockdowns imposed on Shanghai and other cities has affected China’s trade. Current export growth has slowed to levels witnessed at the height of the pandemic in 2020, according to China’s General Administration of Customs (see graphic).

Domestic demand has been hit too, with China’s automobile association revealing that sales in April slumped 48 percent year-on-year as restrictions shuttered factories. Beijing’s zero-COVID policy has tightened the screws on China’s job market, and the country’s most educated seem to be paying the price. The civil services exam has been postponed in the wake of the renewed spread of COVID-19, and has yet to be rescheduled. With more than 10 million students set to graduate this year, the competition for jobs may get intense. This raises the prospects of high unemployment, which could depress China’s growth in the long run. The unemployment rate in the 16–24 age bracket was 16 percent in March. According to hiring firm, Zhaopin, the number of openings targeting fresh graduates also dropped 4.5 percent in the January–March quarter. Some are using job market instability to bide their time and pursue career advancement. This year, nearly 11 percent of graduating master’s students plan to further their education through doctoral and other programmes; in 2021, the proportion of students going in for these degrees was 4 percent.

Rising joblessness was one of the triggers for the Tiananmen Square Incident in 1989, and it still makes the CCP anxious. The CCP elite has been reaching out to the Gen Next. China marks 4 May as its ‘Youth Day’, and CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping took the opportunity to visit Beijing’s Renmin University and pledged to boost university education in the country. Uncertain times necessitate reinforcement of loyalty amongst followers. Ditching his western suit for a ‘revolutionary’ Mao tunic, Xi also called for Renmin University to expand ‘ideological-political’ courses across the country.

The centenary event of the Communist Youth League too became an occasion for Xi to do some plain-speaking and whip up nationalism. Xi made a pitch to youngsters urging them to “confront difficulties” and “overcome hardships”. In his address, he even referenced a slogan—‘my pure love is only for China”—penned by an 18-year-old People’s Liberation Army soldier who died in clashes with the Indian Army in Galwan Valley in 2020.

Also Read: Chinese social media abuzz with rumours of Xi Jinping stepping down for COVID-19 mismanagement

To conclude, the reference to the 2020 confrontation on the India–China border has emerged again. During the Winter Olympics in Beijing, a soldier involved in the Galwan clashes was reserved for the honour to carry the torch. In the past, Xi has referred to a strong army that can win wars. General Manoj Naravane, who demitted office as the Chief of the Army Staff in April, speculated that, “internal or external dynamics” related to the COVID pandemic may have led China to adopt an aggressive posture along the border in 2020. Let’s remember political Lysenkoism is also about quick-fix solutions. Smarting from the failures of his Great Leap Forward campaign, which left the economy in a precarious condition, Mao launched the 1962 war with India to rally the nation behind him. George Orwell wrote “war is peace” since a common enemy always keeps people united. In a politically sensitive year when Xi seeks to cement his grip on power with a third term, he may be tempted to do the same.

Kalpit A. Mankikar is Fellow with Strategic Studies Programme, and is based out of ORF’s Mumbai centre. His research focuses on China, specifically looking at its rise — its domestic politics, diplomacy and techno-nationalism. Views are personal.

The article originally appeared on the Observer Research Foundation website.