Even as the world continues to grapple with the coronavirus pandemic, China has sought to further its strategic aims. In April, China officiated its territorial aggrandisement in the South China Sea by announcing administrative structures to govern much of its nine-dash line claims over the contested Paracels Islands, Macclesfied Bank and the Spratly Islands. Starting mid-April, China stepped up its presence around the disputed Senkaku Islands — setting an all-time high record of operating in the contested space for 65 consecutive days as per the Japanese Coast Guard.

In May, the Chinese National People’s Congress approved a proposal to introduce a contentious national security law in Hong Kong, which would ban “secession, subversion of state power, terrorism, foreign intervention” and permit mainland China’s security apparatus to operate in the semi-autonomous city. Most recently, China and India engaged in a border skirmish which claimed the lives of 20 Indian soldiers, in an incident reported to be the first such “deadly clash in the border area in at least 45 years.”

Amidst its pursuit of long-standing strategic aims, however, Beijing’s advocacy for economic interdependence is set to pick up pace.

Also read: Corps Commander to raise Galwan violence with China & seek status quo in Pangong, other areas

Chinese bid to claim ‘first-mover advantage’

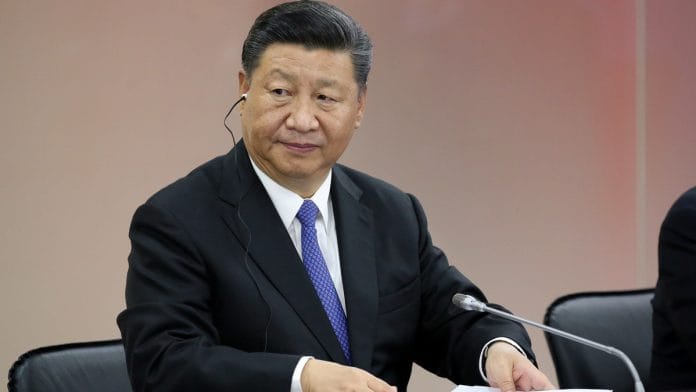

Over the past three years, US President Donald Trump’s anti-globalism message has been met with increased Chinese calls for economic interdependence. Notably, at the 2017 World Economic Forum, Chinese President Xi Jinping said, “We must remain committed to developing global free trade and investment, (and) promote trade and investment liberalization.” China’s turn as the supposed vanguard for economic interdependence stemmed from its intent to preserve its thirty-year stint as the world’s leading manufacturer against a wave of protectionism.

Over that period, the world’s dependence on Chinese goods either accorded it outright monopoly — like in case of China being the largest producer of tires with an estimated 759.3 million units manufactured in 2019, or handed it crucial leverage points — as with China accounting for 40 percent of the world’s requirement for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients.

Following the coronavirus pandemic however, global sentiment against relying extensively on China for crucial imports is set to rise. (China exports plummet by 17% as coronavirus takes its toll) In addition, nations have also eyed this as an opportunity to encourage the “sell where you make” model, attract lucrative foreign investments, and spur a “manufacturing exodus” from China by offering incentives. Hence, in a bid to arrest the decline in its prowess as an exporting behemoth, China is set to further its advocacy for global commerce.

As other nations’ fight with the pandemic impedes their return to normalcy amidst multinational companies becoming increasingly eager to resume production, China has sought to capitalise on its ‘first mover advantage.’ For instance, by March-end, China had already hailed resumption of economic activity, with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology claiming that 98.6 percent of industrial firms had resumed work with 89.9 percent of employees returning to their workplaces. However, China’s attempt to sustain its role as the “factory of the world,” could be met with resistance — starting with the consolidation of anti-China political will in the US.

Also read: Army commanders meet in Delhi to discuss India-China tensions, ‘escalatory trends’ at LAC

US bipartisanship on the ‘America First’ approach to China?

In eyeing its market potentialities, post-Cold War Democrat and Republican administrations prioritised engaging China from an economic standpoint over confronting the strategic challenges it presented. Chiefly, the Bill Clinton administration’s Permanent Normal Trade Relations legislation (which ended US policy of reviewing China’s trade status owing to its record on civil liberties) paved the way for the George W. Bush administration’s facilitation of China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation.

The political folly of this approach was apparent with Trump’s 2016 campaign message which attributed the hollowing out of America’s industrial base to past American policymakers’ ambivalence towards China’s rise as a near-peer competitor. In recognising the cruciality of blue-collar workers from the industrial mid-West in Trump’s 2016 electoral arithmetic, Democrats have thus come around to supporting Trump’s ‘America First’ approach to China.

An early sign of a renewed US bipartisanship was apparent with the Democrats’ support for the 2018 round of US tariffs on China. They referred to it as “a leverage point” against China’s “regulatory barriers, localisation requirements, labour abuses, anticompetitive ‘Made in China 2025’ policy and many other unfair trade practices.” After winning control over the US House of Representatives in the 2018 midterms, Democrats continued their support with complementing initiatives. For instance, even as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi led the charge on assuaging European concerns on fraying transatlantic ties under Trump, her February 2020 visit across the Atlantic saw her to be one with Trump’s campaign against nations opting for Chinese telecoms gear giant Huawei’s 5G propositions.

Furthermore, in reinstating focus on China’s civil liberties record, the House passed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act and the Tibetan Policy and Support Act. Amidst the pandemic, House Democrats have even doubled down to pass the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act. Finally, they are reportedly now also considering the recently approved (Republican-held) Senate bill on delisting noncompliant Chinese companies from US stock exchanges.

Also read: Pharma imports from China can fall. Modi govt must invest in research and development

Rising European calls for reducing dependency on China

Under Trump, transatlantic rifts have widened on account of his decision to view European economies as trade competitors, the US’ withdrawal from the Iran Nuclear Deal and increased pressure on European nations to raise their defence commitments. Europe’s relationship with China has also been a sticking point. For instance, when the UK’s Boris Johnson government announced that the Chinese telecoms giant would build up to 35 percent of its 5G infrastructure, American legislators warned that the move could endanger US-UK intelligence sharing.

However, now in the wake of rising “backlash among Conservative MPs against Chinese investment and a lack of transparency around Beijing’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic,” Johnson has reportedly asked for draft plans to reduce Huawei’s involvement. Moreover, in “entering a period of realism with China,” Johnson announced the UK could ease visa restrictions and put millions of Hong Kongers on a path to citizenship as Beijing looks to impose the discussed security law. Furthermore, in a recent video meeting between the 27 EU member foreign ministers and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the EU’s Foreign Affairs High Representative Josep Borrell called for “a more robust strategy” on China and underscored the importance for Europe “to stay together with the US in order to share concerns and to look for common ground to defend our values and our interests.”

Moreover, beyond rhetoric, the European Union has also sought tighter restrictions against Chinese investments, following rising calls for Europe to have investment safeguards much like the inter-agency mechanism in the US, i.e. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). After last month’s “opportunistic acquisition” of a stake in Norwegian Air by a Chinese government-controlled company, the European Commission announced proposals “intended to prevent foreign investors from using government subsidies to outbid competitors for European assets.”

These proposals evidently pertain to China (which the EU now dubs as a “systemic rival”) given its focus on imposing “conditions on (government) subsidised investors” which through their investments also get their hands on advanced and/or sensitive technology. Case in point, China National Chemical Corp’s 2015 acquisition of Italian tire-giant Pirelli accorded the state-owned entity access to technical knowhow on premium tires. Under the tabled proposals, EU officials could force investors to share acquired technology with competitors.

Hence, increased Chinese advocacy for economic interdependence owing to its centrality in global supply chains, could be met with a renewed transatlantic consensus centered on China.

Kashish Parpiani @kparpiani is a Research Fellow at ORF’s Mumbai Centre. Dhriti Kamdar is a research intern at ORF. Views are personal.

The article was first published on Observer Research Foundation website.

Below is a quote from a colimn by a former bureaucrat.

The European Union’s High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell was spot on when he recently underscored this after the EU-China Strategic Dialogue (external link) on June 9:

‘I understand that for China, to be presented as a systemic rival, is something that looks a little bit controversial. We have to explain what we mean by that and try to express how complex our relationship is, on which things we are disappointed, on which points we need to improve our relations, mainly on the economic side and on the human rights side…

‘I think that it is important also to show our common understanding on many things. For example, on the JCPOA, the Iran nuclear deal, it is clear that there we have an important convergence of positions.

‘On Afghanistan, we share the same interest of ensuring the stability of the country once the retreat of the American troops has taken effect and the negotiations between the Afghan government and the Taliban reach an end.

‘On Africa, cooperation to fight coronavirus, debt relief and all efforts to increase cooperation. In order to fight against the pandemic, the world needs more cooperation and less confrontation…

‘It is clear that we do not have the same political system. It is clear that China defends its political system as we do with ours. It is clear that China has a global ambition. But, at the same time, I do not think that China is playing a role that can threaten world peace.

‘They committed once and again to the fact that they want to be present in the world and play a global role, but they do not have military ambitions and they do not want to use force and participate in military conflicts. What do we mean by “rivalry”?

‘Well, let’s go over this word. Sometimes, there are differences on interests and on values. That is a fact of life. It is also a fact of life that we have to cooperate, because you cannot imagine how we can solve the climate challenge without strong cooperation with China.

‘You cannot build a multilateral world without China participating in it effectively, not in a “Chinese way”, but in a way that can be accepted by everybody. I think these kind of explanations are good, because I can tell you that we have talked a lot about what it means to be a “systemic rival”.’

World standing against Chinese hegemony is requirement of the time.

China virus.