As China boosts overseas investment through Belt & Road Initiative, it’s dictating both the terms of financing and a broader set of technological applications.

High-level trade talks last week between the U.S. and China grabbed headlines around the world, but in many ways they were beside the point. In the years ahead, tariffs and industrial policy — the main focus of the talks — will probably matter less in the growing competition between the two countries, while another, much quieter initiative will matter more.

As China boosts overseas investment through its Belt and Road infrastructure program, it is increasingly dictating not just the terms of financing but also a broader set of technological applications. In doing so, it is altering the global competitive landscape by defining and exporting technical standards for everything from artificial intelligence to hydropower.

This push into global standards-setting has gone largely unnoticed. That’s partly because it’s boring: Even broaching the topic will make investors’ eyes glaze over, and few Western governments have given it much thought.

But it’s also partly by design. The process has so far mostly unfolded domestically, and in Chinese, as China’s government has sought to develop its own set of industrial standards for companies operating within its borders. That has made the effort mostly opaque to outsiders. Yet regulators are now starting to translate those standards into English — a clear sign that they’re meant to be exported overseas. And that should worry China’s competitors.

For decades, America’s ability to set domestic standards that would then spread globally benefited its economy greatly. As a recent paper by the East-West Center put it, “standards serve as bridges between developing innovations and the marketization and industrialization of those innovations.” The specification of even everyday items such as USB ports has given American companies a strong advantage in selling goods in other markets.

Patents are the key conduit of this process. As standard-setting in any industry progresses, the companies that own the technology on which the standards are based benefit by either selling their equipment or licensing their patents. Telecoms are a classic example. Qualcomm Inc., which owns key patents for LTE, 3G, and 4G technology, has received billions of dollars in royalties in recent years — including almost $8 billion in China alone in 2014. And that’s in an industry where standards are set through a complex global process; when countries set standards unilaterally, the benefits for their homegrown companies can be even more pronounced.

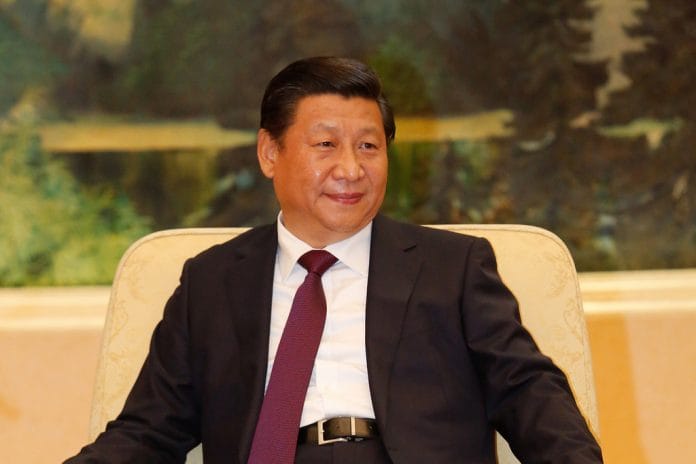

This is where President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign-policy program comes in. Most analyses of the Belt and Road initiative focus on whether individual projects will become profitable or will leave China further mired in debt. Yet the return on investment for a port in Sri Lanka or a rail line in Thailand matters less to Chinese officials than the ability to push participating countries to adopt Chinese standards on everything from construction to finance to data management. For just one example, China is exporting key technical standards for the construction of high-speed rail through these projects — in large part to circumvent standards set by Western players.

Developing countries tend to voluntarily adopt standards set by high-income economies. But China’s government has taken a much more proactive role. Instead of trying to influence the likes of Pakistan, Thailand, and Myanmar by changing hearts and minds, it wants to convince them to change their nuts and bolts — and their data-management practices to boot. In this context, China’s recent revisions to its National Standardization Law and its Cyber Security Law look far more significant; they could reverberate far beyond its borders.

Although few people would contest China’s right to determine its own technological standards, exporting those standards is another matter altogether. Billions of dollars in equipment sales and patent royalties are up for grabs in this competition. To the extent that China’s standards supplant Western ones, it will represent a direct threat to the profitability of non-Chinese companies.

This push won’t directly challenge the ability of American or European companies to innovate. But it will undoubtedly challenge their ability to commercialize technology in other markets. That emerging competition should be of utmost concern to companies and policy makers alike — and that’s one reason China is glad that the issue isn’t even part of the discussion. —Bloomberg.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.