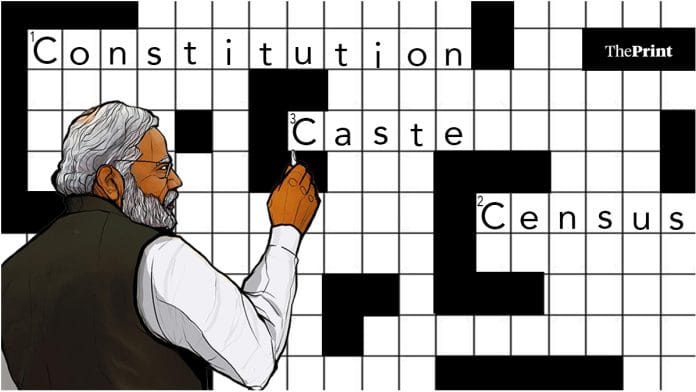

An unintended consequence of the BJP’s continuous hegemony is that it has flattened divisions between opposition intellectuals. Unlike two decades ago, very few commentators have directly opposed the recent announcement of caste enumeration alongside the census. Instead, they are reduced to clamouring about technicalities. The pro-BJP intelligentsia, meanwhile, toes the party line anyway.

In that sense, Shekhar Gupta is courageous to have stuck to his guns. Gupta argues that caste enumeration will inevitably snowball into caste-based welfarism, eventually culminating in private sector reservations. According to his ideal schema for progress, none of this is optimal.

Gupta’s approach can be loosely described as non-interventionist liberalism — a position characteristic of libertarianism. But we need not split ideological hairs here. Suffice it to say, Gupta has raised similar arguments for a free market in the past, and is a nostalgic supporter of the long-obsolete Swatantra Party.

Yet in the case of caste enumeration, to borrow the words of Argentinian President Javier Milei — himself a libertarian — the argument is “using a noble cause to protect caste interests.” Milei has persistently used “caste” as a metaphor for a closed group of Argentine elites — unlike India, where caste is real. Still, the essence of Milei’s “anti-caste” campaign applies: caste domination and market liberty are fundamentally contradictory. In India, an unregulated capitalist economy does little more than reproduce feudal regulations.

Also read: Caste census is a bad idea whose time has come. Much worse lies ahead

Markets don’t erase caste—they repackage it

A study published just last month found little evidence that lower castes — Dalits and OBCs, Hindu and Muslim — have been freed from caste-based occupations. It identified the “inter-generational predominance of Hindu general castes in Grade A and B service sector jobs, business, and trading” in Uttar Pradesh. Nominal freedom matters little to this huge population still under the “despotism of custom”, as John Stuart Mill would put it.

“Oh, Uttar Pradesh,” sighs the reader. Sadly, this is not confined to a single state. Fed up with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s tea-seller stories, Mallikarjun Kharge once reminded him during a campaign speech that even if his family had a tea stall, no one would have drunk from it. Kharge is from Karnataka. CPI(M) MP K Radhakrishnan has previously narrated how a Dalit started a soda manufacturing company in Kottayam, Kerala, and it was silently boycotted.

Indeed, researcher and public policy professor Aseem Prakash’s work, based on interviews with several Dalit entrepreneurs, shows that the relationship between caste and capitalism does not operate on abstract notions of merit and efficiency. It is deeply embedded in social relationships, not governed by the impersonal contracts typical of modern market ideals.

Similarly, Barbara Harriss-White argues that caste networks play a crucial role in regulating business — networks that upper castes exploit most effectively. Meanwhile, the occupational ties of Dalits are reinforced by their concentration at the lowest rungs in stigmatised industries such as those leatherwork, cleaning, brick kilns, and the waste economy. The literature on this is not abundant, but it is conclusive.

This reflects a pattern not of exclusion but of ‘adverse or unfavourable inclusion,’ as Aseem Prakash would call it — where Dalits participate in the market on unequal terms, shaped by enduring caste hierarchies.

In Western liberal societies, non-aggression may be interchangeable with non-interference, since the state is often the most aggressive actor. But the social condition of Dalits offers a counterexample. For them, protection comes through intervention; non-intervention means everyday aggression from the rest of caste society.

David Mosse, drawing on several ethnographies, argues that caste identity continues to shape modern urban job opportunities in often subtle and hard-to-detect ways. Individuals migrating from stagnating agricultural sectors are sorted into jobs by skill, insecurity, danger, toxicity, and status — gradients deeply informed by caste. This likely holds true for many OBCs, but current data leaves a vacuum by focusing solely on two poles of the labour-capital relationship, and does not include the majority of OBCs.

Which rational capitalist cannot see that this is an inefficient use of human capital?

Also read: Bihar census identified the privileged and under-privileged castes. Go national now

Free markets need state intervention to break caste

Market liberty can indeed be a positive force — in societies that have overcome feudal overgrowth. But in societies still governed by caste norms and customs, freeing the market from state regulation achieves the opposite of liberty. The idea of the free market holds that the state should intervene as little as possible — but emphasis must be placed as much on “possible” as on “little.”

A just state would find it impossible not to intervene against caste norms. Intervention to establish individual rights and personal sovereignty is what actually enables freer market access. The liberal philosopher John Locke offers a justification for such acts: a legitimate government is allowed to redirect private property for public use. This is the doctrine of eminent domain.

We already have a tried and tested instrument to counter caste-based oligopoly: reservations. They are not ideal, but they are the least-worst option — and they work.

Reservations in private education and eventually in organised, white-collar private-sector jobs would be inconvenient in the short term and benefit only a small share of SCs, STs, and OBCs. Yet they provide a good way to integrate these backward groups into the capitalist economy. It would be cruel to ask them to wait for public-sector expansion or rely solely on intermittent appeals for greater inclusivity from the organised private sector.

Without a constitutional mandate, such incorporation is unlikely. Seventy years have passed without much inclusivity; the problem won’t resolve itself one fine morning.

For the state to intervene — or for capitalists to correct course — we need data. Caste enumeration could lay the groundwork for study and gradual reform in the private sector, but only if it counts all castes, including the privileged ones, and collects economic data as well.

Christopher Hitchens once quipped, “A serious ruling class will not lie to itself in its own statistics.” It shouldn’t suppress data either. Gupta assumes, even before the census is conducted, that the data will fuel demands for private sector reservation. We would be glad if the census proves otherwise — that India is already caste-equitised.

Sociological data, in itself, hasn’t plunged any country into crisis. Nor has caste data in the three Indian states that collected it. It is thus prudent to take a leap in good faith than to make a priori assumptions about the outcome. In fact, with or without a caste census, there is libertarian logic in implementing private sector reservations. Principled liberals should be calling for it — it is, after all, in the ‘national interest’ — incidentally, the title of Gupta’s column in ThePrint.

This article is in response to ThePrint Editor-in-Chief Shekhar Gupta’s National Interest column published on 3 May 2025.

Sumit Samos is an MSc graduate from Oxford University. He tweets @SumitSamos.

Arjun Ramachandran is a PhD scholar at the University of Hyderabad. He tweets @___arjun______.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)

I can guarantee you these guys have never ran a private business. It’s funny how they pretend as if there is no other country on this planet for these businesses to move on.

Private sector reservation will only make these companies move to other locations and that will be the end of corporate sector in this country.

Seriously who the hell are these uneducated educated communist idiots ? We are not some attractive market where companies would “die to work”.

Also what’s the proof that there is caste discrimination? You think companies ask about caste when you are being interviewed ? Have these idiots even given any interview for a private sector job or are they jobless intellectuals like Karl Marx ? No one cares about caste in a private sector ? In a country where there is a dearth of skilled workers, these idiots think that people will be busy with caste ?

What a bunch of clowns. Do it and you will see the end of this country

I think it is time we accept that caste will never not be the most important factor in India. We should conduct a caste census every year and divide the employment opportunities in public and private sector next year based on the census breakup. And further extension of the same logic would demand that extremely socially deprived subcastes in the scheduled castes and tribes also be alloted individual subquotas. Otherwise how will be negate the dominance of selected subcastes in the quota pie? The government should just make a register of the thousand odd subcastes in India and like the annual budget announce how much employment they are entitled to that year. If 100 % of the jobs are decided on the basis of caste there would be no need for constant rejigging of 50% ceilings or 70% ceilings. Caste (or better yet subcaste) should be the first and foremost determinant to employment, and merit within the caste subgroup should be the next one. That will actually improve social harmony and prevent friction since everyone would know from birth what exactly they are entitled to and would only ever compete with people from their own subcaste. It is better to accept what seems electorally foreordained and ensure a smooth transition.