What could possibly link modern fashion, oppressed peasants driven to rebellion and the censorship of commercial theatre in India? It’s a colour that almost all of us have worn at one time or another. Indigo.

When we don our favourite pair of blue jeans, which gets their unique colour from indigo, most of us do not know that this vibrant shade, has an extremely violent and complex past.

To unravel this, we need to look back.

Indigo cultivation

Indigo has been grown and processed in India since ancient times and was one of the products that attracted European traders. In the 19th century, it was grown across the southern districts of undivided Bengal and filled the coffers of the English East India Company as an extremely profitable import to Britain.

The system of cultivation was inherently exploitative. The planters, overwhelmingly European, owned the ‘factories’ (indigo processing units) but sourced the crop from the peasants of the surrounding villages. The Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal calculated that the peasant lost Rs 7 per bigha (approximately 0.62 acres) every time he cultivated indigo instead of other crops like rice. To the actual cost of cultivation was added the bribes which he had to pay to every servant of the indigo factory with whom he interacted. Unsurprisingly, the peasants didn’t wish to sow indigo.

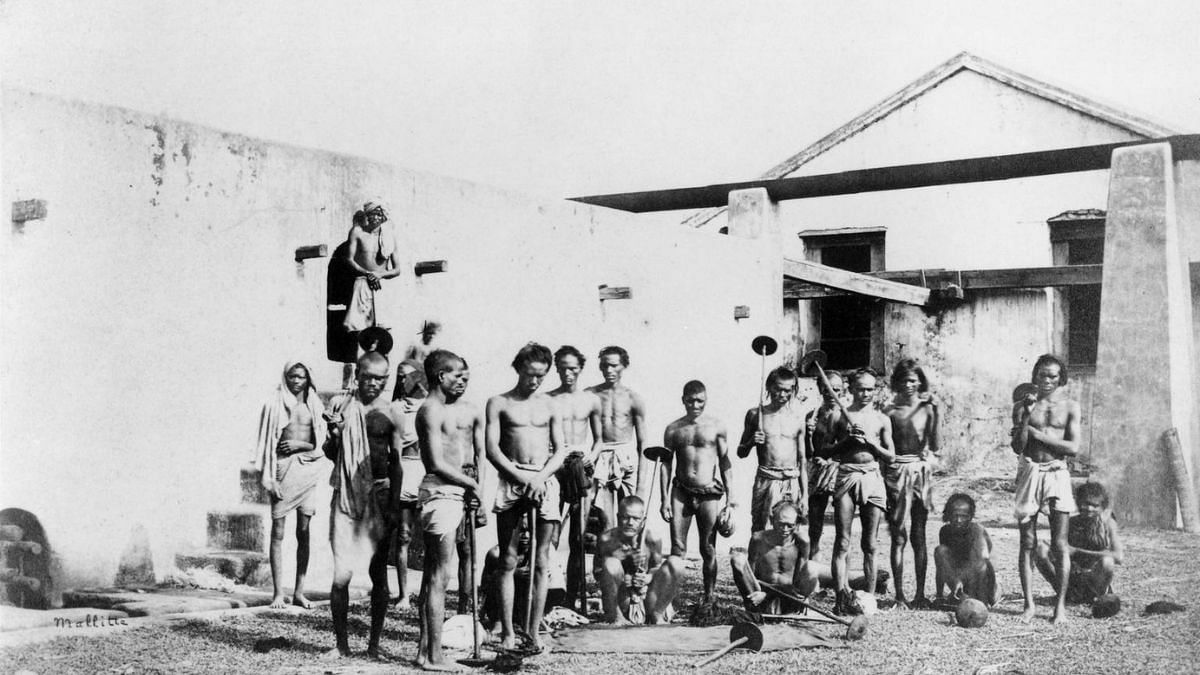

The European planters, on the other hand, coerced them to do so by bringing false lawsuits against those who refused, as well as by threats, beatings, imprisonment, murder, riots and arson. The core of the problem was the system of dadan (advance payment), which was used by the planters to entice the cultivators into sowing indigo. Once they accepted it, they were at the mercy of the planters. Those who refused were shot down, speared through and kidnapped and confined in large numbers. It was said that ‘Not a chest of indigo reached England without being stained by human blood’.

The rebellion

Finally, the cultivators in Bengal had had enough. In the spring of 1859, less than a year after the Great Revolt of 1857 had been brutally suppressed, thousands refused to sow indigo. The European planters blamed a notice issued by Ashley Eden, the magistrate of Barasat, which stated that the sowing indigo (or not) was the peasant’s choice and he could not be forced to do otherwise. As the rebellion spearheaded by Digambar Biswas and Bishnucharan Biswas of Jessore, spread rapidly through the districts of Nadia, Barasat, Pabna, Khulna, Jessore, Birbhum, Burdwan and Murshidabad, the planters hardened their stand. Under intense pressure from the latter, the government passed a pro-planter Indigo Act (Act XI of 1860), which only served to stiffen peasant resistance.

Just one example will illustrate their grit and determination when faced with the far better-equipped forces sent by the planters. A German missionary at Krishnanagar (in Nadia), Rev. C. Bomwetsch, who was fully sympathetic to the peasants’ cause, described the fierce but organised resistance by the cultivators of Ballavpur village who supplied indigo to the Ratnapur factory of Nadia.

When the planter sent hundreds of lathials (men trained to fight with lathis or specially designed long bamboo poles) to ‘punish’ them, the peasants responded swiftly. They divided themselves into six ‘companies’, each wielding its weapon of choice—bow and arrow, slings, brass plates (thrown horizontally at the enemy), brickbats, lathis and spears. Neither did the women lag behind, using kitchen equipment as weapons very effectively. The planter’s forces were driven back and the village was spared the burden of sowing indigo that season.

The turmoil caused by the rebellion compelled the British colonial government to institute the Indigo Commission (1860) to investigate and report on the recent events. The Commission’s report provided ample evidence of the injustices of the indigo cultivation system. The stranglehold of the planters over the peasants was broken in Bengal, and soon after the indigo factories shifted to Bihar.

Also read: Railways weren’t Britain’s ‘gift’ to India—we paid with blood, sweat & humiliation

Neel Darpan

The plight of the cultivators was movingly depicted by Dinabandhu Mitra in his play Neel Darpan (literally, the indigo planting mirror), which was published anonymously in 1860. Mitra was an inspector in the Post and Telegraph Department who had travelled through the indigo districts in 1860. In 1861, he sent a copy of the play to the Anglo-Irish priest, Rev. James Long who ran the Church Missionary Society school in Calcutta where Mitra had been educated. Long, with two decades of missionary service in India behind him, firmly believed that the vernacular accounts were a vital indicator of the true feelings of Indians toward British rule and had already begun compiling lists of such writings.

The Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, Sir John Grant heard about the play from Long’s acquaintance, William Seton-Carr, Secretary to the Government of Bengal and requested an English translation of it. The translation, by the renowned Bengali author, Michael Madhusudan Dutt was soon complete. Long added an introduction and published around 500 copies in 1861. Some of the copies were distributed in official government envelopes, which made it appear that the work had official sanction.

The indigo planters were outraged. A case was filed against Long by William Brett, owner of the newspaper Englishman, the Landholders Association of British India and the planter body. At the end of the trial for libel, Long was sentenced to a month in jail and fined Rs 1,000. Many among the educated elite in Calcutta opposed the biased verdict and the fine was paid on Long’s behalf by the Bengali zamindar and author Kaliprasanna Singha.

The play went on to become the first one to be staged commercially in Bengal at the National Theatre in Calcutta in 1872. The next year, the staging of the play in Lucknow triggered one of the major turning points in the history of theatre and censorship—the Dramatic Performances Act of 1876 was imposed. In her autobiographical account Amar Katha, Binodini (better known as Nati Binodini, a pioneering theatre actor of Bengal who was part of the Lucknow performance) narrated the violent response of the White-majority audience who were outraged by the portrayal of the European planters.

“Eventually we came to that part of the play where Rogue Saheb molests Khetromoni….at which point Torap [enters] …and proceeds to strangle the saheb, using his knees to straddle him and pounding him with blows. Immediately there was a hue and cry from among the saheb spectators…Some of the red-faced goras unsheathed their swords and jumped onto the stage. Half a dozen people were hard-pressed trying to control them…We thought this was the end…now they would surely cut us up into pieces.”

The denim blue

For many decades now, indigo has been a forgotten crop. The massive demand for it prompted Germany to pump millions of dollars into research to develop a synthetic version. Once German synthetic indigo entered the market at the turn of the 19th century, the cultivation and manufacture of organic indigo in India declined dramatically.

Though its cultivation ceased, the fascination with the colour continued across the world. The transformation of denim from a tough fabric made in Nȋmes, France (denim from de Nȋmes) and used by sailors, into jeans, an indispensable part of modern global fashion, is well known. But few know that the original blue of the sailor’s apparel came from natural indigo. Even today, it is indigo (whether natural or synthetic) among all other chemical blue dyes which gives denim its unique blue shade and fading qualities.

The story of indigo is thus a long and chequered one. The next time you slip on your blue denims, perhaps you will remember some of it.

Dr. Krishnokoli Hazra teaches History at the undergraduate level in Kolkata. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)