In April 2022, it was announced that India’s flagship rural broadband project: Bharat Broadband Network Ltd (BBNL), the special purpose vehicle set up to implement BharatNet would merge with Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd (BSNL), the national telecom service provider.

Three linked arguments have been made for the merger. First, BharatNet’s repeated failure to meet its implementation targets has greatly slowed progress toward its stated goal of providing high-speed broadband connectivity to India’s 250,000 village panchayats. Second, the project’s costs have skyrocketed because of these delays. The cost of laying one kilometre of optic fibre cable (OFC), for instance, has doubled between 2020-21 and 2021-22, and the overall outlay for the project has tripled from INR 20,100 crore to over INR 61,100 crore. Third, the merger of BBNL with BSNL is expected to yield synergies which will improve project coordination, contain costs, and accelerate outcomes.

BharatNet’s approach toward the government-set deadlines has exemplified the notion that the sooner one falls behind, the more time one will have to catch up. The project began life as the National Optical Fibre Network (NOFN) in 2011 but little progress was made between 2011 and 2014. The present government inherited the initiative, rebranded it as BharatNet in 2015, and projected 2018 as its completion date. Operational setbacks and poor execution soon began to make this seem unrealistic, and at different points, target dates of 2020 and 2021 were agreed upon. The National Digital Communication Policy envisaged connectivity of 1 Gbps for every panchayat by 2020, which would be upgraded to 10 Gbps by 2022. Yet another deferral was in store though. In his Independence Day speech last year, Prime Minister Modi declared that within the next 1,000 days, i.e., by mid-2024, every Indian village would be connected by OFC. These plans seem to have been unsettled now, and 2025 is being regarded as the new date by which villages may expect to receive broadband.

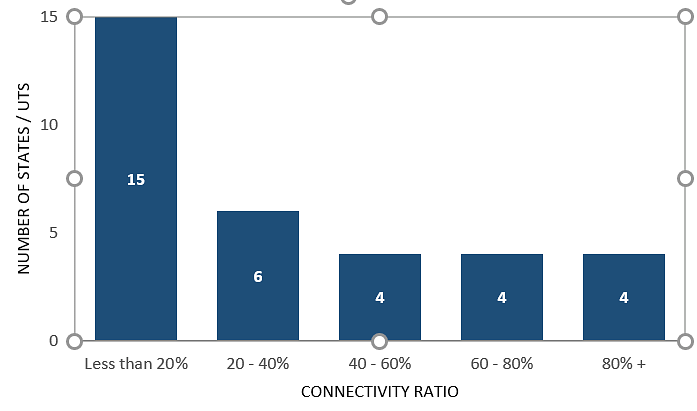

There is now a broad consensus that the project management of BharatNet so far has been sub-standard. According to a recent ministerial statement in the Rajya Sabha, as of March 2022, only 27 percent of the expected number of villages had received network connectivity. The concept of connectivity ratio (CR) is important to consider here. CR is defined as the ratio between (a) the number of villages in a state that have been made service-ready by BharatNet, and (b) the total number of villages in that state. A connectivity ratio of 20 percent, therefore, would mean that in a particular state, 20 out of every 100 villages are service-ready. Of India’s 33 states and union territories (UTs), only two: Punjab and Chandigarh have been able to achieve a CR of 90 percent, eight others have a CR of over 60 percent, and at the lower extreme, Himachal Pradesh has attained a CR of only 2.1 percent.

Less than a third of India’s villages are service-ready

Moreover, there continues to be a significant difference between the number of villages to which OFC has been laid, and those which are actually connected to the OFC and enjoy functioning broadband. This discrepancy has existed since BharatNet’s earliest phases and peaked during the pandemic. Since late 2020, however, there has been a decline in both the rate of installing OFC and of providing connectivity itself.

Across the country, BharatNet’s quality of service (QoS) has long plagued panchayats and villages. Complaints by village officials about frequent line faults, connection outages, and the lack of response to requests for service and repairs have grown increasingly common. These QoS issues are partly explained by a 2021 CAG report that revealed that the agreements governing BharatNet’s implementation did not include any provisions for penalising the agencies tasked with maintaining the OFC network. Efforts by state governments and project personnel to liaise with BharatNet’s central administrators to rectify these inefficiencies have yielded little result. This has prompted a fragmentation of operations whereby several states have created special purpose vehicles to execute the project themselves.

Will the merger help?

It is not clear how the BBNL-BSNL merger might act as a panacea for rural broadband. BSNL itself has incurred major losses over the last five years and developed certain notoriety for slow decision-making and red-tapism. The telecom company is currently in the process of receiving a capital infusion of INR 44,720 crore as part of a revival plan to put it back on its feet, support technology up-gradation and internal restructuring, and enable the allocation of 4G spectrum.

BBNL and BSNL have engaged in the past, and the outcomes have been less than inspiring. BBNL depends heavily on BSNL to provide connectivity and bandwidth at the block, panchayat, and village levels, but on numerous occasions, BSNL has been unable to deliver on its commitments. For several years now, BBNL has been cutting back on outsourcing BharatNet-related work to BSNL as the latter has not always utilised BBNL’s funds effectively, sometimes even using them for unsanctioned purposes. BBNL has even had to “take back” a project originally entrusted to BSNL—for maintaining the OFC for 120,000 panchayats—and assign it to another agency instead. Given this background of uneasy and sometimes downright unsuccessful collaboration, it is hard to imagine BSNL assuming all the responsibilities that BSNL currently manages, and ensuring the operation, maintenance and utilisation of the already-laid OFC network as well.

Perhaps the only advantage BSNL might bring to Bharatnet after the merger is that it already has over 2 million fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) connections and is adding around 100,00 new connections every month. This growing base of fixed-access platforms may prove valuable. In other respects, BSNL has demonstrated little capacity for supporting BBNL. It now seems that some of BharatNet’s weaknesses and delays may have stemmed from BSNL’s inertia.

Under the circumstances, one cannot but wonder if the merger of BBNL and BSNL will be a case of a faltering force meeting an immovable object. The shortcomings of executing BharatNet chiefly in partnership with public sector undertakings have been apparent for years. But it was only in July 2021 that BBNL finally floated a tender for a public-private partnership (PPP) and began bid interactions with potential private partners. The private sector response was guarded. Companies were well aware of the project’s deficiencies. They knew too that by being made responsible for operating and upgrading BharatNet across 16 states for the next 30 years as the PPP’s terms stipulated, they would find themselves troubleshooting on a gargantuan scale without adequate incentives. Not surprisingly, not a single bid was received and the tender was eventually cancelled in February 2022.

The private sector’s lack of interest amounts to a resounding vote of no-confidence in BharatNet. Following the BBNL-BSNL merger, the government intends to issue a revised PPP plan later in 2022. But unless the new plan is significantly different from the last one, there is no reason to believe that it will be received any differently.

Also Read: India’s telecom sector has sufficient competition despite consolidation: Centre

Conclusion

BharatNet’s goal of connecting 250,000 panchayats and 600,000 villages with high-speed broadband is central to the government’s vision of India emerging as one of the world’s largest connected nations and “1.5 billion Indians being connected to the Internet over the next two years”.

The project is backed by strong political will and commitment. The Prime Minister has emphasised that ‘rural digital connectivity is a no longer mere aspiration but has become a necessity’. Besides, whilst presenting the Union Budget 2022, the Finance Minister stated that 5 percent of all collections under the Universal Services Obligation Fund (USOF) would be used to enable broadband and mobile services across rural India and that the laying of OFC under BharatNet would proceed apace in 2022-23.

On-ground implementation, however, has always been the project’s Achilles’ heel. It is a moot question whether the BBNL-BSNL merger will be able to transform BharatNet into the agile, fast-moving enterprise that it needs to become. The recent performance history of both entities, whether considered separately or in conjunction, has been subpar. And in the meantime, despite the good intentions that drive BharatNet, it has become a byword for operational inefficiency, unreliable QOS, and missed targets. Unless these elements are addressed in the post-merger phase, broadband for all will remain unattainable, and a key chapter in India’s development story will remain unwritten.

Anirban Sarma is a Senior Fellow at ORF. His research focuses on media, ICTs, and technology-enhanced learning. Views are personal.

This article was originally published in ORF and has been republished here with permission.