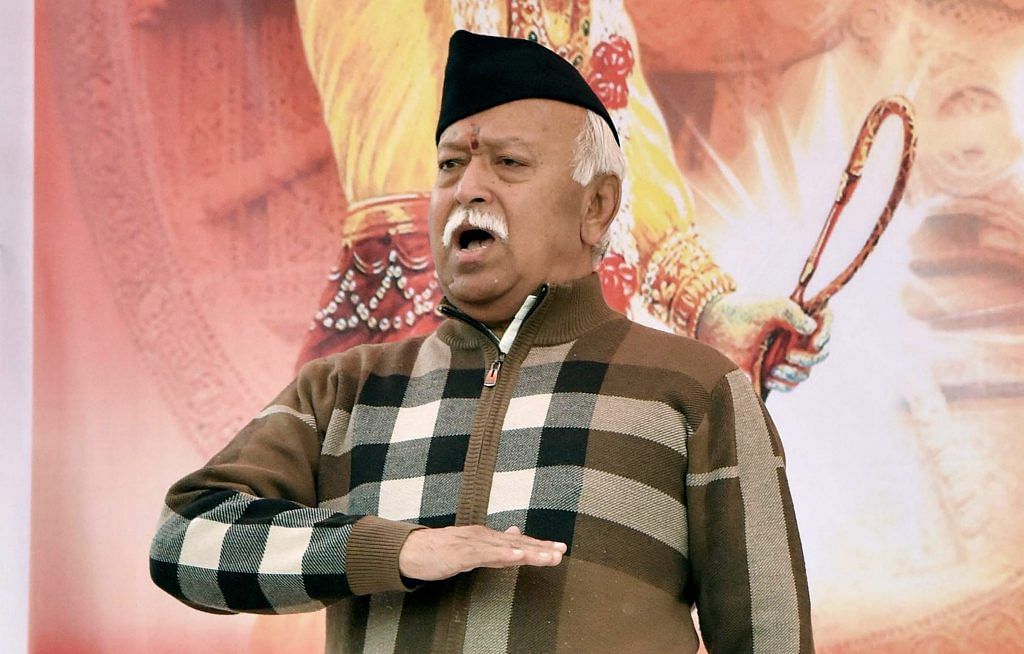

RSS chief wants both swayamsevaks and civilians to be trained by the Indian Army. His comment goes against the democratic spirit of the Constitution.

Mohan Bhagwat’s statement that the RSS could ‘prepare the society’ faster than the Indian Army has been condemned for the wrong reasons.

Congress chief Rahul Gandhi calls it ‘an insult…a disrespect for those who have died for the nation’, while Sanjay Singh of AAP describes it as an outrageous statement. Interestingly, the central claim of Bhagwat’s speech at Muzaffarpur was entirely missed.

Bhagwat actually made two powerful arguments, which need to be unpacked for a nuanced understanding of the RSS’s imagination of Indian society. It is imperative to remind ourselves about the group’s founding principles, which evoke the Hindus to get ready as soldiers to fight internal and external threats.

Discipline versus militarisation

His first argument was actually a self-clarification. Bhagwat said:

“The Sangh is neither a military nor a paramilitary organisation, rather it is like a ‘parivarik sangathan’ (family organisation) where discipline is practised like the Army.”

This clarification is very important. The RSS, unlike the Hindu Mahasabha of V.D. Savarkar, never openly called for ‘militarisation’ of Hindus. The RSS always makes a distinction between physical training for self-defence and militarisation. This distinction helps the Sangh to present itself as a ‘cultural’ organisation in a strict constitutional sense to avoid possible legal complexities.

It is worth noting that this distinction between discipline and militarisation was not always seen sympathetically by the governments in the past. In a letter to chief ministers written on 7 December 1947, for example, Jawaharlal Nehru noted:

“We have a great deal of evidence to show that the RSS is an organisation which is in the nature of a private army and which is definitely proceeding on the strictest Nazi lines, even following the technique of organisation… their activity more and more goes beyond (the)…limits and it is desirable for provincial governments to keep a watchful eye and to take such actions as they may deem necessary.” (J. L. Nehru, Letters to Chief Ministers-1947-1964, Oxford University Press 1985, pp. 56-57)

After the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, the RSS was finally banned in 1948. Although RSS’s involvement in Gandhi’s murder was ruled out completely, the activities of the organisation were regarded as unlawful and anti-national. The text of the government order which banned the RSS said:

“…It has been found that in several parts of the country individual members of the RSS have indulged in acts of violence …and have collected illicit arms and ammunitions. They have been found circulating leaflets exhorting people to resort to terrorist methods, to collect firearms, to create disaffection against the government and suborn the police and military.” (Des Raj Goyal, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Radha Krishna Prakashan, 1979, pp. 201-202).

The self-description of the RSS as a parivarik and disciplined organisation, thus, is actually embedded in a very complicated past. That is the reason why Bhagwat does not make any comparison between the RSS and the Army; instead, he tries to justify RSS’s ‘discipline-oriented Shakha networks’ by appropriating the patriotic image of Indian armed forces.

This is precisely what the RSS’s official clarification also reiterates. It says:

“Bhagwat ji had said that if situation arises and the Constitution permits, Indian Army would take six months to prepare the society whereas Sangh swayamsevaks can be trained in three days, as swayamsevaks practise discipline regularly.”

This was in no way a comparison between the Indian Army and the Sangh swayamsevaks, but it was a comparison between general society and swayamsevaks. Both are to be trained by the Indian Army only.

Does the Constitution prefer militarisation?

Bhagwat’s second point was equally interesting. He evoked the Constitution of India to transform the Indian society—like RSS—into a disciplined entity. The clarification by the RSS, it seems further elaborates this point. It asserts that both the RSS as well as Indian society should be trained by the Army.

This straightforward appeal for militarisation of Indian society raises two relevant questions: what is the Constitutional imagination of an ideal Indian society? What ought to be purpose of Army-like training for Indian citizens?

The Constitution of India, we must remember, envisages a peaceful national society. Article 39, for instance says, “the State shall strive to promote…a social order in which justice, social, economic and political, shall inform all the institutions of the national life.” Although Article 51 A (d) calls upon all the citizens of India “to defend the country and render national service when called upon to do so”, the Constitution does not make any reference to Army-like training for ordinary citizens.

In fact, the term ‘armed forces’ appears only 14 times in the Constitution, especially with regard to separation of powers between the state and the Centre. The Constitution, in this sense, upholds the supremacy of citizenship by clearly defining the powers of elected government with regard to armed forces.

Bhagwat’s comment, hence, goes against the civilian and democratic spirit of the Constitution. However, as an intelligent politician, he continues to employ the terms like the ‘Constitution’, ‘Army’ and patriotism as ideological metaphors to legitimise RSS’s interpretation of Indian society—a society in a war-like situation!

Hilal Ahmed is an associate professor at CSDS.