Recent legal commentary on the developments in Jammu and Kashmir has focused largely on Article 370 of the Constitution. The present controversy is as much about federalism as it is about the very nature of constituent power. Is the redrawing of the map of Jammu and Kashmir constitutional?

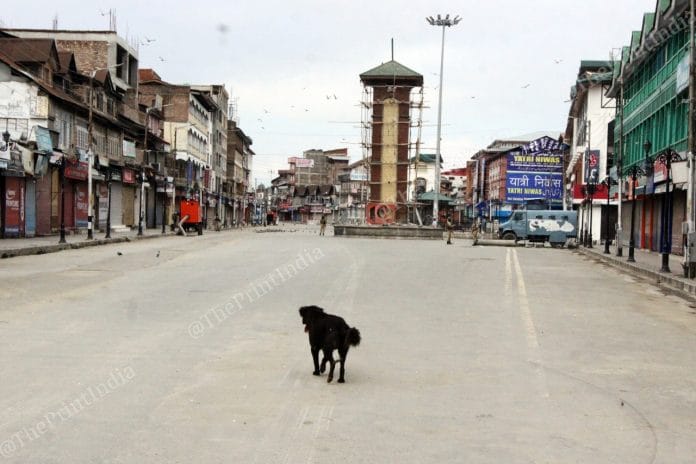

As others and I have argued, the revocation of Article 370 raises a number of constitutional questions, whose adjudication poses a serious challenge for the Supreme Court. However, as debates over Article 370 proceed, it is worth paying attention to another legal matter that has been relatively less examined, namely the bifurcation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories.

What the Constitution says

Article 3 of the Constitution empowers Parliament to alter state boundaries and create new states (the provision specifies that state includes union territories). Parliament can do this “by law” – that is to say, this does not require a constitutional amendment. This provision has been a major reason why scholars have long questioned India’s federal credentials. Even though the Constitution separates lawmaking powers between the Union and the states, Article 3 means that states do not have an independent political identity.

Although Article 3 does not require either a constitutional amendment or consent by the state/s involved in the alteration and creation exercise, it does require one form of engagement with the relevant state/s. As per the provision, the Bill for alteration/creation must be referred “by the President to the legislature of that state for expressing its views thereon”. Does the bifurcation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir follow this constitutionally mandated procedure?

Also read: India needs tips from Israel on how to handle Kashmir. Blocking network is not one of them

What the Supreme Court says

The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019 creates two union territories: the union territory of Ladakh (comprising Kargil and Leh districts) and the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (comprising the remaining territory of the original state of Jammu and Kashmir once Kargil and Leh districts have been carved out). The Act has been passed by Parliament at a time when the Jammu and Kashmir state legislature has not been in session, and the Governor (a central appointee) has performed the role of the legislature. Ordinarily, such stepping in is standard practice, but can it count as valid in the present instance?

Two Supreme Court cases shed some light on this matter. The first is a 1966 decision in the Mangal Singh case that dealt with the Punjab Reorganisation Act, 1966. The primary issue here was the composition of the Legislative Assembly of Haryana. Though the court recognised that Parliament had considerable powers with regard to creating new state entities, it declared that “the power which Parliament may exercise by law is supplemental, incidental or consequential to the admission, establishment or formation of a state as contemplated by the Constitution, and is not power to override the constitutional scheme”.

The second is a 2009 decision in the Pradeep Chaudhary case. Here, the Supreme Court considered the Uttar Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2000. The issue was whether the bill that is referred to the relevant state legislature, as required by Article 3, can differ from the eventual law that is enacted by Parliament. Interestingly, the court diluted the requirements in Article 3 in some respects by holding that where the bill has been amended, “the amended parliamentary bill need not be referred to the state legislature again for obtaining its fresh views”. However, it did emphasise – and this was crucial to its ruling – that the views of state legislature would have to be considered. In this case, it underlined that “detailed discussions have taken place amongst the members of the legislative assembly”.

Also read: The constitutional questions that arise from the end of Jammu and Kashmir as a state

SC doctrine raises two concerns

The established Supreme Court doctrine raises two concerns regarding the ongoing controversy. First, the Pradeep Chaudhary case makes it clear that the relevant state legislature must have a chance to debate the proposal to alter state boundaries, and that its views must be considered. The proposal can be slightly different from the final law and the views of the state legislature need not be accepted, but a reference to the state legislature is constitutionally inviolable.

Second, and herein lies the puzzle of the present case, is the fact that the state of Jammu and Kashmir has a separate constitution. This not only makes the reference to the state legislature all the more necessary, but invites the question of whether there must be a threshold beyond a mere reference.

The use of a simple parliamentary law to do away with a state constitution – giving it its own political identity in the classic federal sense – seems to plainly fall foul of the ruling in the Mangal Singh case, which established that the overall constitutional scheme must be maintained in the exercise of Article 3.

What the additional threshold must be for a change of this kind remains an open question. It would require the state of Jammu and Kashmir to give its consent to doing away with its own constitution, but it is not clear whether this can be done if the basic structure doctrine also applies to the state constitution.

Regardless of what one makes of this puzzle, it does seem clear that some additional requirement must exist beyond what is required for other states. Otherwise, the separate constitution of the state of Jammu and Kashmir has no legal meaning. As we debate this, it is worth keeping in mind that, in this case, even the basic requirement that exists with regard to other states has not been met.

Also read: Article 370 has put us in a dilemma: Should we choose Constitution’s letter or its spirit?

Madhav Khosla is a Junior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. His book, India’s Founding Moment: The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracy, is forthcoming by Harvard University Press. Views are personal.

Ahaa, its fastidious conversation regarding this piece of writing here

at this blog, I have read all that, so now me also commenting here.

I ask if Mr Madhav Khosla birth is Constitutional. And when he will die, whether that will be constitutional. I have all the freedom to ask anything I like.

My heart tells me the apex court will uphold all these constitutional changes.

It’s not just heart, your head will also tell the same thing. In democracy the defeated ones can’t rule through courts.

@ashok

What happened to you! Your pro Pakistan and anti national heart is beating different today?!