Once upon a time, Ashoka University carried the reputation of being India’s private JNU—a place that promised space for dissent, critical thinking, and courage in academia. But today, that image is quietly fading. The university is under fire for its silence and subtle distancing from Professor Ali Khan Mahmudabad after his arrest. A letter by one of Ashoka’s founders—now widely circulated among students and alumni—tries to explain why the institution didn’t stand by its employee.

The letter frames activism and liberal arts as separate spheres, as though you can study power without ever challenging it. It shrinks the idea of academic freedom down to just peer-reviewed papers and classroom lectures—anything beyond that, like writing an opinion piece or speaking up in public, is conveniently dismissed as personal indulgence, not protected expression. In it, the founder says that “any public outcry about a political opinion an academic may express on social media is not an attack on academic freedom”, but anyone with a basic understanding of academic freedom can tell you that in democratic societies, it includes the right to engage in public debate, especially on matters of public concern. Academic freedom isn’t just about what happens inside the ivory tower. It’s about the right to ask hard questions in public.

But the heart of the letter isn’t really about academic freedom or institutional silence. It’s about money. One line in particular has lingered in the minds of many who read it: “Try running this place without us. Then you’ll know the value of money—‘aatey daal ka bhaav pata chal jayega’.” One can critique him, say he’s reducing everything to funds and donors. But if we’re honest, don’t we, as a society, believe this too? That money talks, and when it does, everyone else should listen? Whether it’s universities, everyday life, or even friendships—don’t we all know what happens when funding walks out of the room? Maybe what this letter says out loud is what many of us quietly accept already.

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve heard people say that in the end, it’s benefits and money that matter. We love to celebrate moral courage—until there’s a real cost attached. Social morality, ethics, standing up for what’s right are held up as values, but only when they don’t come with a price tag. And when someone actually dares to pay that price, what do we say? That they’re naïve, idealistic, even foolish. Isn’t that the same thread running through this argument? The idea that principles are fine, as long as they don’t disturb the comfort of those holding the purse strings. This isn’t just a founder’s mindset. It’s a mirror.

Building on that same logic, the letter leans heavily on the idea of “Institutional Neutrality.” That Ashoka, as a university governed by law, must stay above the noise—must be neutral. But here’s the thing: silence is never truly neutral. Especially in moments when speech comes with a cost, choosing not to speak is also a choice. It’s a political act in itself.

Also read: The world sees Ali Khan Mahmudabad’s arrest first, not all-party delegations

Money and morality

The entire letter is rooted in a simple idea: That institutions must choose neutrality, because taking a stand might affect business. That, when it comes down to ideals versus investments, it’s the investments that must win. But imagine a world built entirely on that logic—a world where fundraising is the only compass, where power is the only language. It’s the kind of world where climate warnings are ignored because oil stocks are booming. Where media bends the truth because advertisers demand it. Where rights are negotiable, but returns aren’t.

And when such an idea fails—and it often does—it’s not politicians or corporations who step in to fix it. We turn to our thinkers, our writers, our teachers. We turn to universities. Because if places dedicated to knowledge and critical thinking can’t be the first to push back, who will?

In the end, what we’re hearing is this: A founder—an elite, powerful, and influential member of society—saying that people with means have no responsibility to uphold values or ethics if it comes at a cost. That somehow, money and morality exist on two separate tracks. That being funds-oriented gives you the license to completely disengage from social discourse. But does it, really?

Even businesses—especially those with power and reach—are increasingly being held accountable for their social footprint. From climate responsibility to workplace ethics, we now expect corporations to stand for more than just bottom lines. So when the founder compares a university to a commercial venture, the question isn’t just offensive—it’s illogical. When did businesses lose their social obligations?

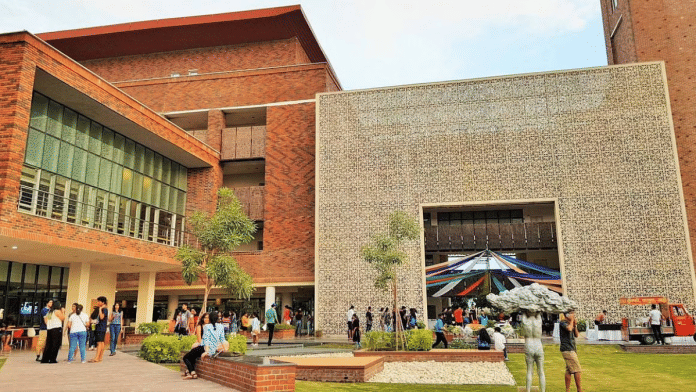

What makes a university more than just a collection of buildings and courses is its courage to ask hard questions—and stand by those who do. If even these spaces retreat into the safety of neutrality and hide behind the wall of funding, what hope do we have left for the rest of society? Ashoka was imagined as a space to challenge, question, and think freely. If that imagination folds the moment it’s tested, then maybe the real crisis isn’t just of academic freedom—but of conviction.

Amana Begam Ansari is a columnist, writer, TV news panelist. She runs a weekly YouTube show called ‘India This Week by Amana and Khalid’. She tweets @Amana_Ansari. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

If Monali’s argument in her comment is representative of an education from Ashoka University, then I wonder if the institute deserves the vaunted reputation it enjoys. For logical reasoning, the most essential of any decent education, seems to be sorely missing from the university’s common curriculum.

Monali’s argument would have respectable if the persecuted/prosecuted professor had made any statement which was contrary to the principles of the constitution or the values of civil society. Instead, it was the complaints filed against the professor which were baseless. More so the one by the head of Haryana’s State Commission for Women. That one was blatantly false, illogical, unmaintainable, and hence reprehensible.

The university, at the very least, should have criticized the complaints, especially the second one, for their untenability. After all, there is something called civics which universities are traditionally expected to justify, and teach. And not merely read out, in passing, in the courses they conduct on it.

https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/seriously-discussed-walking-away-ashoka-university-co-founder-says-amid-row/article69657569.ece

Amana (the author) is unerringly perceptive and accurate. The responses by Mr. Sanjeev Bikhchandani (co-founder of Ashoka University), which are quoted in The Hindu, are frighteningly self-entitled and pernicious.

Mr. Bikhchandani’s statements reveal some of the major flaws that exist in our society, and key reasons why our nation seems to be perpetually stuck in the same rut.

Only those who have acquired their money and positions by honest and fair means will know the value of civil rights and justice, and the latter’s indispensibility for the material progress of a society.

Unfortunately, most of the rich and elite in India are habituated to the use of dishonest and unfair means for their advantage. Why would they care for values? Why would they strive for the betterment of society? Why would they fund institutions which could chip away at the unfair privileges they enjoy?

That’s the tragedy of not just our universities which depend on private funding, but also our media which is similarly beholden.

ThePrint is an example. It proclaims all the right intentions that are essential for performance by its industry, but it falls short of fulfilling them. And life being what it is, short even by an inch inevitably becomes as damaging as short by a mile.

This isnt just about money. It is about who bears the consequence for certain actions. The university should not be expected to lend its legitimacy with every individual associated with it. If the professor made a remark as a private individual why should the university be forced to support. He did not consult them before involving them. Regardless of the actual consequnce i.e. money or something else people should not be obligated to be dragged with you. No one gave you the right to represent them.