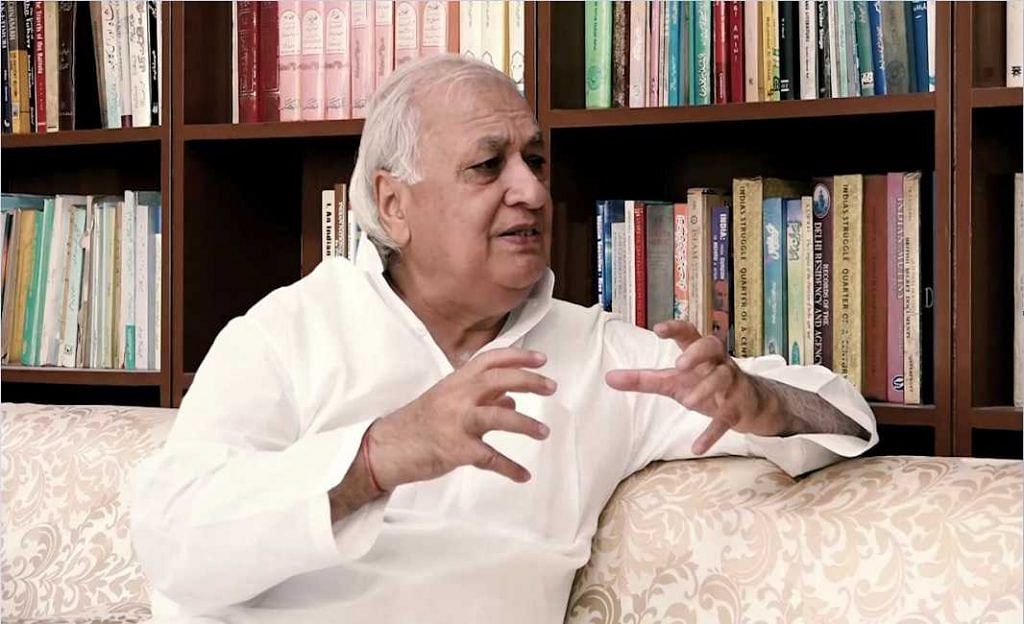

Former union minister Arif Mohammad Khan’s viral video interaction with Karan Thapar on the question of how Muslims are viewing PM Narendra Modi’s victory displayed his characteristic arrogant style of arguing, designed simply to demonstrate his intellectual supremacy. But what he revealed instead was intellectual sophistry, and an outdated and simplistic understanding of both politics and secularism.

Khan wanted to show that Muslims do not feel isolated after the BJP’s Lok Sabha election victory, and evoked what he called his version of secularism. He described himself as a believer of the Constitution, but his claims actually go against the basic premises of Indian secularism and constitutional assurances. He exhibited an aggressive refusal to acknowledge the impact of the anti-Muslim sentiment created in the last five years.

Technical versus political

I agree with Khan on three things regarding the idea of political representation in India. First, the Constitution recognises voters’ identity in purely secular terms. Hence, voters must not be identified on religious and caste lines.

Second, the Constitution does not define the term minority. Hence, minority/majority must be decided contextually. Recognising Hindus as permanent majority and Muslims as permanent minority is problematic because it shows the colonial mindset.

Third, Muslims need not necessarily be represented by Muslims. An MP represents all voters of his/her constituency.

Also read: Muslim MPs, MLAs don’t always work for Muslims. See Akhilesh govt response to Muzaffarnagar

However, the problem arises when these technicalities are invoked to justify a few overtly political tendencies.

- The remark that an MP must represent his/her electorate cannot justify what Maneka Gandhi said to Muslim voters of her constituency in a public meeting during her campaign in Sultanpur, Uttar Pradesh. She categorically said that if Muslims did not vote for her, she would not work for them at all.

- Obviously, Muslims are not a permanent minority in the strict colonial sense. However, it does not mean that the minority status of Muslims is not at all constitutional.

One must remember that following The National Commission for Minorities Act, 1992, the government (including the Modi government) recognises Muslims and other minority religious groups as national minorities. The purpose of this recognition is not to offer special rights to Muslims, but to implement the provisions of the Constitution so that a level-playing ground may be provided to all citizens.

The Modi government did not deviate from this principle. The recognition of Sachar Report as a ‘policy source’ for designing various schemes for the upliftment of minorities is a revealing example.

Also read: BJP is more interested in Sachar Report on Muslims than Congress now

Communal secularism

It appears that Arif Mohammad Khan still lives in 1986, with his brand of rigid legal secularism. His secularism does not allow him to think beyond the Shah Bano case. He treats it as a reference point to reflect on all the issues and concerns that Muslims encounter in contemporary India.

He makes two points in this regard. First, Muslims are responsible for their own problems (Khan said “the seeds of the problems are within”). Hence, there is no need to question anyone, including the state.

Second, Hindutva does not pose any challenge. Instead, communalism is practiced by Hindu and Muslim aggressive leaders who make provocative statements that must not be taken seriously. To him, the secularism of extreme equality — the secularism that does not believe in majority and minority and creates a clear dividing line between religion and politics — is the final solution to communalism.

This uncomplicated straightforward communalism versus secularism formulation is highly problematic. The contemporary form of communalism cannot simply be called a Hindu-Muslim tussle.

On the contrary, what we witness today is Hindutva-dominated communalism. As an organised mode of politics, it produces anti-Muslim discourse, creates conditions that often lead to violence against a particular Muslim community/group or individual, and above all, it nurtures hate against the victims of violence.

In fact, Khan’s secularism of extreme equality actually goes well with Hindutva communalism primarily because it denies any legal protection to minorities.

We must remember that Khan’s secularism of extreme equality actually echoes what L.K. Advani used to call pseudo-secularism — that implies that non-BJP/RSS version of secularism is false because of its inherent anti-Hindu and/or pro-minority inclination.

Constitutional secularism

Secularism of extreme equality, in any case, goes against the values of constitutional secularism, which allows the Indian state to celebrate India’s religious and cultural diversity, without associating itself with any religion or culture. Unlike the French or American versions of secularism, Indian secularism remains sympathetic to the everyday life of religious communities. This is exactly what political theorist Rajeev Bhargava calls the distinctiveness of Indian secularism.

Khan, it appears, is unaware of this uniquely evolved post-colonial Indian tradition of secularism.

Also read: The good Muslim-bad Muslim binary is as old as Nehru

Yes, Khan is a good Muslim

Arif Mohammad Khan’s Muslim bashing in the name of secularism transforms him into a good Muslim — an acceptable metaphor in postcolonial Muslim politics.

As an elite Muslim, he seems to employ his cultural capital (he is upper caste, well-educated, and has a strong political-economic background) to achieve the status of a Muslim leader. His adherence to existing political correctness allows him to argue that he wants to speak as an Indian, not as a Muslim. And finally, his suggestion that Muslims should stop blaming Hindutva reflects his desperation to be a part of the Sabka Saath brigade.

The author is associate professor at CSDS, and author of the new book titled Siyasi Muslims: A Story of Political Islams in India. Views are personal.