Till the mid-1970s, cinema was the only popular visual medium in India and the only strong visual connect we had was with film stars who sang in borrowed voices. So, with exceptions like Kishore Kumar, who was also an actor, how would we put faces to the voices that guided our lives? Fortunately, we had radio. And announcers—the word ‘radio jockey’ was yet to be in used in the country. Inasmuch, Mahalaya in Bengal would be incomplete without the voice of Birendra Krishna Bhadra. People used to tune in to listen to radio newscasters Surajit Sen, Melville de Mellow, or Barun Haldar; so strong was their presence in our lives. Jasdev Singh and Sushil Doshi’s cricket commentary on the radio made non-Hindi speakers comfortable with colloquial Hindi in an unimposing way.

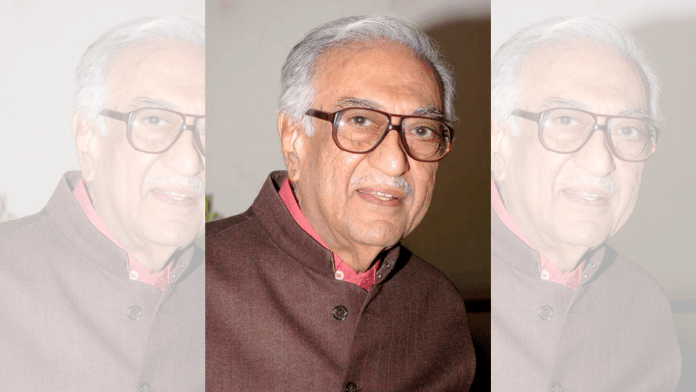

And then there was Ameen Sayani.

In the ’60s and ’70s, there were radio announcers who would do a roll call of the credits before a song played, and then there was Sayani who didn’t merely announce the names of the songs or films but presented them and appreciated the song’s peculiarities too. Just the way a good radio cricket commentator could create visuals of a game in the minds of the listener, Sayani’s presentations rang like thunderous ovations for each song.

He could connect with people naturally. “Aap Hindi bahut acchi bolte hain,” he said to us, though our mother tongue wasn’t Hindi. This warm statement opened doors for introductions and conversations. To the broadcaster, good performance was key—not only in his film commercials and radio announcements but also in the highly competitive Bournvita Quiz Contest that he hosted every Sunday afternoon. There were no “wrong answers”, only “I’m afraid not” responses before the question passed to the next team. Sayani was the quintessential presenter and storyteller who would never permit the intensity of a competition to rob the enjoyment of it all.

With his long-tailed “Ji haaaan” tapering off with a slight nasality, and his salutation “Behno aur bhaiyon”, Sayani’s voice was inimitable — and the most imitated one. In 2012 in Mumbai, we heard a familiar recorded voice in a vada pav shop. It was a commendable imitation of Sayani’s voice, but the vada pav was more original.

Sayani’s influence extended beyond just radio; he played a pivotal role in the evolution of Hindi film music as well. His ability to connect with audiences through heartfelt presentations made him a beloved figure in the industry.

Also read: Kishore Kumar had 30 dogs of all pedigrees. ‘Trained to bite only Income Tax…

A pioneer in many ways

Throughout his career in radio, Sayani spoke in Hindustani, which is surprising, as the broadcaster came from a family that spoke only Gujarati and Urdu. He studied in an English medium school and later at St. Xavier’s College, Bombay, where he honed his English-speaking skills. But he excelled in Hindustani in his iconic radio programme Binaca Geetmala, for which he is widely remembered. The first superstar of radio service in India, Sayani would endorse products, engage with filmmakers for promotions, play a role or two (as in the 1965 movie Bhoot Bungla), and announce the film cast (for the 1965 film Teen Devian). He would also be offered to write dialogues, something he refused to venture into after an unsatisfactory attempt in Sawan Kumar’s Hawas (1974).

Sayani’s greatest achievement was popularising Hindi film music across India by instilling a sense of competition not only within the music fraternity but also among listeners. In a country where the idea of a ‘countdown’ or song rankings was largely unknown, Sayani stack-ranked popular Hindi film songs in Binaca Geetmala, probably inspired by the billboards in the United States. That made him stand out in the radio industry. He started the practice in 1954, and it took some time for listeners to gauge what song rankings meant. Once they understood how it worked, all hell broke loose: Thousands of postcards were sent to the channel with song requests via “listeners’ clubs”; some were genuine, some were not. These clubs were like fan groups obsessed with imaginary rivalries between singers and composers. Needless to say, the programme was the most awaited one every week.

Paan and cigarette shops in towns, and panchayat offices in villages, would see huge crowds with self-anointed experts debating the selection or exclusion of a particular song or a set of songs. The annual countdown was like an event where people who did not have radio sets would visit friends and relatives who had one. Binaca Geetmala turned more into a celebration of the glamour quotient of a song. Between 8 and 9 pm every Wednesday when the programme was aired, everyone sat glued to their radio sets. The concept of ‘prime time’ on radio was born.

Anirudha Bhattacharjee, an alumnus of IIT Kharagpur, is a SAP consultant who dabbles in music as a hobby. Balaji Vittal is an alumnus of Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and works for Concentrix. Anirudha and Balaji received the President’s National Award for Best Book on Cinema for their debut book, R.D. Burman: The Man, The Music. Anirudha has five books to his credit, Balaji four. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)