Summer reading’ has always struck me as an odd tradition. It was pioneered in places that craved sunshine, which India possesses in broiling overabundance. Of course, one must always be wary about advancing generalisations about India—but that image of a reader lying on green grass, under a bright sun, engrossed in a paperback: It’s just not an Indian image.

Until the proliferation of the affordable smartphone, literate Indians used to be voracious consumers of print: Newspapers, magazines, pamphlets. The democratisation of book reading occurred relatively later in India. In the Raj era, Bengali gentlemen of means, the most vigorous mimics of the British, invested in Victorian novels. And Bengali high society abounded with boasting and parlour games on English literature—who read what, who owned what.

The intellectual regeneration of this period, incubating novel ideas, broadened the reading habits of relatively well-heeled Indians. From Punjab to Bengal and Delhi to Andhra, authors of pulpy and “serious” fiction in native languages went on to acquire cult followings in the 20th century. Nothing approaching the literary ferment in Russia—where the appearance of Pushkin precipitated the advent of a proudly national literature—could be replicated in polyglot India.

Writers in English, the language of the elite in colonial India, had only a tiny readership in republican India. Even after the economic liberalisation of the 1990s, the value of Indian writing in English was measured at home by its reception in the West. There was a flight of talent: Some of the most successful Indian writers in English of the late 1980s and 1990s domiciled themselves abroad.

Also read: Mini JLFs sprouting across India. Lit fest boom in Nagpur, Ranchi, Kanpur, Indore, Kokrajhar

Salman Rushdie bizarrely pronounced their output the “most valuable contribution India has yet made to the world of books”. It fell to VS Naipaul, the shrewdest observer of India since Mahatma Gandhi, to notice the fatal disability of the Indo-Anglian literary culture: “the books are published by people outside, judged by people outside, and to a large extent bought by people outside.”

Today, just as all the political virtues prized by a generation of émigré Indian writers in English are becoming extinct, India can be said to have an authentically homegrown market for books by Indian authors writing in English. India still cannot support its writers, but it contains now an immense readership for bound products of all genres. For writers whose livelihood is not dependent solely upon royalties, this is deeply gratifying.

So, summer reading lists may not be such an oddity after all. But what follows, based on the books I read recently, should perhaps be called a late monsoon reading list. Some of the books on it were published this year. Others were published years ago. All of them have this in common: They deserve a wide readership.

-

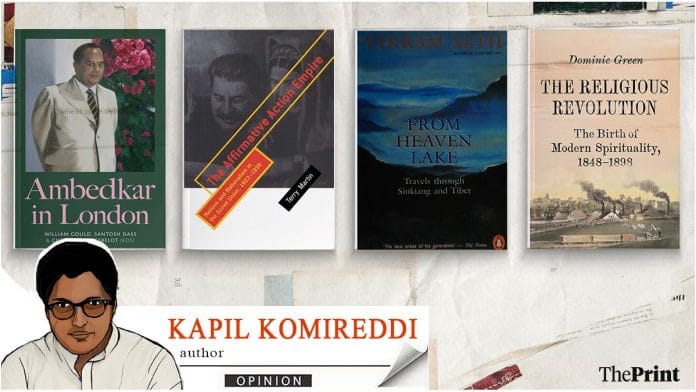

Ambedkar in London (Hurst, 2022)

Edited by William Gould, Santosh Dass, Christophe Jaffrelot

BR Ambedkar spent two spells as a student in London (1916-1917 and 1920-1924). These were crucial years in the life of one of India’s most important founding personalities. All Indians were in the colonial gutter, but Bhimrao was looking at the stars. His brilliant mind and formidable intellect, overcoming the prejudices of race and caste, had no equal in the freedom movement. Jawaharlal Nehru was a commonplace student in England. Gandhi immersed himself in Victorian fads. Ambedkar was a man apart.

Edited by the preeminent India hands William Gould, Santosh Dass, and Christophe Jaffrelot, this volume doesn’t just fill the gaps in our knowledge of Ambedkar’s life in London—the period that shaped his political life in India—but also opens our eyes to the many movements for human dignity, autonomy, and emancipation, from Europe to Africa, inspired by Ambedkar’s life.

Ambedkar in London, forthcoming from Hurst in November, is made indispensable by the mere fact of its existence.

-

The Affirmative Action Empire Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939 (Cornell University Press, 2001)

Terry Martin

Kurapaty is the densely wooded area outside Minsk where Belarusian intellectuals—champions of a distinct Belarusian identity—were slaughtered on Stalin’s orders between 1937 and 1941. Until I read Martin’s outstanding work of scholarship, my mind recalled the haunting image of Kurapaty whenever I thought about the USSR’s consolidation.

Martin upends our understanding of national identity in the early USSR. Rather than snuffing out non-Russian identities, Moscow’s new masters sought to foster them. Russia, the keystone of the multi-ethnic Soviet Union, was treated as the fount of reaction—and its influence and importance were balanced by subsidising, sponsoring, and financing non-Russian languages, cultures, and “territories”.

This policy ended in the late 1930s. But, from Ukraine to Georgia, its effects are still visible in the post-Soviet world. (Marshal Tito had attempted similarly to tame the Serbians by granting significant autonomy to Kosovo and Vojvodina. While Mao, who mobilised people of all ethnicities in the cause of the proletariat, betrayed everyone who was gullible enough to believe him by affirming the supremacy of the Han Chinese immediately after gaining power.)

Affirmative Action Empire seems eerily relevant as our own government seeks to establish the primacy of one language and religion.

Also read: Geetanjali Shree won 1st Booker for Hindi novel. Regional authors must ask for right price now

-

From Heaven Lake: Travels through Sinkiang and Tibet (Chatto & Windus, 1983)

Vikram Seth

This book, published before I was born, originated in a journal kept by a doctoral student hitchhiking his way through China in 1982. The published product is a book unlike any other. As Seth writes, India and China, “despite their contiguity, have had almost no contact in the course of history”. From Heaven Lake is a rare record of China through Indian eyes.

There Seth is, gossiping about “Laj Kapoor” with Chinese guards. Here he is, observing the cruelty of Han rule over the Muslim Uyghurs who, having been forced to forgo their own language, cannot communicate with their grandparents. The acuity of Seth’s vision is matched by the vividness of his brilliant prose. He misses nothing. I return to this book once every few years. Nothing like it exists or can now come into existence.

-

The Religious Revolution: The Birth of Modern Spirituality, 1848-1898 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022)

Dominic Green

Dominic Green is one of the most despised figures in Anglo-American print media because he writes at the speed at which others speak. Would an obscure journal with an enormous endowment like 1,500 words on medieval Nordic poetry? He will deliver. A lively piece on Beau Brummell for the weekend section? With you by 6 pm.

Green’s new book, The Religious Revolution, demonstrates the depth of his learning and erudition. This is intellectual history with an overawing ensemble cast—Wagner, Emerson, Nietzsche, Madame Blavatsky, Gandhi, Vivekananda, Herzl. Green ably weaves their lives into an absorbing story of the rise of spirituality—which, he contends convincingly, played as important a role as science in shaping the modern world. The Religious Revolution is unlikely to endear its author to those who envy him—but it is certain to enrich and enliven the minds of all who read it.

Kapil Komireddi is the author of Malevolent Republic: A Short History of the New India. Views are personal.