The modern concept of human rights is historically linked to Western schools of thought, particularly the Enlightenment, and broadly associated with reason, individual freedom, and inherent human dignity. However, this has been critically reassessed, as human rights scholar Norani Othman (1999) forcefully asked:

“Does only Western discourse have the capacity to generate such a conception of human rights?”

It is now widely established that cultures and societies across the world offer rich foundations for developing human rights theories. The core values of human rights—dignity, justice, and equality—date back to ancient times and have long influenced the legal and moral orders of societies.

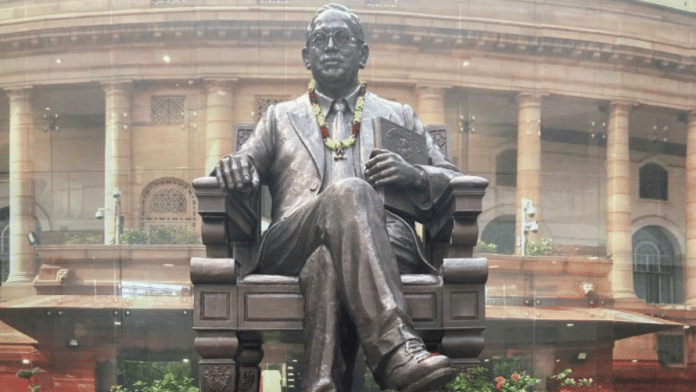

Ambedkar’s human rights legacy—Ahead of the world

In the Indian context, Dr BR Ambedkar, a visionary crusader for social justice, not only indigenised the concept of human rights but also reinstated human values in a society long dehumanised by the Varna system. He embodied the universal principles of human rights long before they were formally recognised on the global stage. Ambedkar transformed the discourse on caste oppression into a conversation about fundamental human rights—an approach both novel and historically unprecedented.

Even before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted in 1948, Ambedkar had already emerged as a passionate advocate for the rights of India’s oppressed communities, laying the groundwork for a broader and more inclusive vision of equality and dignity. While the formal language of ‘human rights’ was still evolving during his lifetime, the underlying principles had existed for centuries. A close reading of his writings and activism reveals a deeply cosmopolitan vision of justice. His political and legal practice—always guided by principle—became central to the global human rights discourse.

Dr. Ambedkar’s pursuit of social justice and the annihilation of caste demonstrates how he adopted and redefined the concept of human rights to address India’s unique historical and social realities. He selectively engaged with global conceptions of justice and rights, adapting them for India’s struggle against discrimination. Though some have criticised him for “copying” elements of other constitutions, Ambedkar’s work was a deliberate effort to institutionalise universal human rights in India—rendering them relevant to its complex and diverse society.

Also read: Ambedkar Jayanti is changing. It’s now a dance party & vote-seeking festival

Mahad Satyagraha: Right to water as social revolution

One of the clearest examples of Ambedkar’s human rights advocacy was his leadership in the Mahad Satyagraha of 1927. In this movement, Dalits marched to public water tanks to assert their right to drink from them. This marked the beginning of a powerful discourse on equality in access to life’s most basic necessities. For the first time in Indian jurisprudence, basic needs were elevated to the status of human rights. Ambedkar framed the right to water as a matter of social revolution—challenging systemic human rights violations and igniting broader movements against institutional discrimination.

This struggle not only demanded rights-based equality but also galvanised the masses to assert their dignity. Babasaheb drew inspiration from the ideals of ‘liberty, equality, and fraternity’, popularised during the French Revolution. He invoked these ideals in his Mahad speech, likening the satyagraha to the storming of the Bastille—an act that shattered feudal privileges in France. By framing the fight against caste discrimination within global human rights discourse, Ambedkar reinforced the universality of these principles and demonstrated their urgent relevance to the Indian context.

From Buddha to rights: Local roots, universal vision

Ambedkar’s vision transcended the mere adoption of Western ideals. Although he drew inspiration from global movements, he grounded his understanding of universal human rights in the teachings of the Buddha. He traced the essential principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity back to Buddhist philosophy, articulated centuries before the French Revolution. He believed that while the French Revolution was a giant step forward, it ultimately failed to achieve true equality. These ideals, he argued, could only be realised in a society that embraced the moral and ethical teachings of the Buddha.

This convergence of Buddhist ethics and human rights has also been observed by scholars. As argued by Damien Keown (1998), the moral precepts of Buddha have given rise to the idea of rights—such as the right to life, derived from the precept not to kill, or the right to property, derived from the precept not to steal.

By nativising the concept of human rights—reviving the Buddha’s message, Ambedkar did not merely transform the lexicon of justice; he radically challenged India’s long-established and unfair social hierarchies. He envisioned what would later become a cornerstone of global human rights activism—the interdependence of rights. While Western debates often focused narrowly on civil and political rights, Ambedkar drew attention to the historical neglect of economic and social rights. He rejected the separation of rights into isolated categories, insisting that freedom required personal liberty, human dignity and social justice.

Also read: Reading Dalit literature changes established accounts of nationalism, colonialism & modernity

Temple entry: Dignity over devotion

Unlike conventional movements, Ambedkar’s call for temple entry was not about religious devotion. Babasaheb’s aim was clear: he did not seek entry to worship, but to protest denial. It was a bold challenge to a society that dehumanised Dalits.

In his speech during the Kalaram Temple Satyagraha, Ambedkar said, “Whether the Hindu mind is willing to accept the elevated aspirations of the new era—that man must be treated as man; he must be given humanitarian rights; human dignity should be established—is going to be tested through this Satyagraha.”

The temple became a symbolic battleground for the soul of the nation. Ambedkar was not merely advocating entry; he was leading a movement for rights—against untouchability, Brahmin supremacy, and for the full recognition of Dalits as equal human beings.

Ambedkar was the first reformer to systematically theorise caste as a human rights issue—not just a social structure. Before his intervention, caste was often treated as a cultural or religious feature. Ambedkar exposed its brutally oppressive, exclusionary and dehumanising nature, and rooted his critique in the universal principles of equality, dignity, and justice.

Why Ambedkar rejected cultural relativism

The conflict between universal human rights and cultural relativism remains one of the most significant debates in social justice. Cultural relativism holds that moral norms and rights are context-dependent and should not be imposed across cultures. Ambedkar categorically rejected this view when applied to caste.

He dismantled the idea that practices such as untouchability, endogamy, and occupational segregation were mere “cultural differences” to be tolerated. For Ambedkar, the Varna system was not a benign tradition but a religiously codified regime of graded inequality—one that rendered systemic violence into moral and legal obligation. He argued that Hinduism’s moral system stifled empathy for the oppressed and promoted the sentiment of “righteous indignation” against untouchables, dulling people’s sense of justice and made them complicit through religious conditioning. This institutionalised dehumanisation, he argued, could never be defended or excused as cultural specificity.

In Annihilation of Caste, he wrote: “You must have the courage to tell the Hindus that what is wrong with them is their religion—the religion which has produced in them this notion of the sacredness of caste.”

Ambedkar’s universalist stance made clear that appeals to tradition were often tools to preserve hierarchy. His drafting of the Constitution operationalised this vision, enshrining rights that transcended parochialism. For him, cultural relativism was not pluralism—it was the ideological armour of oppression, shielding dominant groups from accountability. No custom, he insisted, could justify the denial of dignity.

Also read: Seeing Ambedkar as Dalit icon is narrow. Understand his feminist vision for Indian women

Ambedkar vs Marx: A better path for India

From the Mahad Satyagraha to temple entry movements, Ambedkar laid the groundwork for using human rights as tools against caste oppression. This foundation would crystallise into a constitutional vision—a revolutionary alternative to Marx’s class-centric approach. Karl Marx viewed human rights as a bourgeois illusion—a deceptive veil that concealed capitalist exploitation behind lofty rhetoric about freedom. For Marx, rights like liberty and property served as defensive mechanisms for the ruling class, converting workers into isolated, competitive individuals rather than uniting them in collective solidarity. True emancipation, he insisted, could only come from overthrowing class systems.

But in India, where domination is structured not just by class but by caste, Marx’s revolutionary remedy didn’t work.

Dr. Ambedkar, by contrast, saw human rights as transformative instruments. Where Marx had foreseen rhetoric, Ambedkar saw tools of liberation. His constitutional protections—such as reservations, fundamental rights, and equal citizenship—were not just legal shields but weapons against caste tyranny.

Whereas Marx’s proletariat were theoretically “free” under capitalism, India’s Dalits were not even theoretically granted that freedom under Brahminical rule. Babasaheb engineered a social revolution, opening a door to power that economic revolution alone could not provide. Through India’s Constitution, he granted Dalits and marginalised communities what they had been systematically denied for millennia—legal personhood.

His assertion—“Political democracy cannot last unless there lies at the base of it social democracy”—exposed the poverty of Marxist thought in addressing India’s unique caste-based oppression. The persistence of caste oppression today justifies Babasaheb: if economic progress could eradicate caste, as Marxist argued, why do well-off Dalits and Adivasis still face exclusion and humiliation at the systemic level across all levels of society—from villages to top universities to corporate workspaces to government institutions?

Also read: Ambedkar took on Brahmins in Indian media for their loyalty to the Congress party

Ambedkar’s blueprint for justice still works

As India confronts deepening economic inequality and persistent caste injustice, Dr. Ambedkar’s vision remains more prescient than ever. The Constitution’s fundamental rights have enabled Dalit assertion and socio-educational mobility in ways that class struggle alone could never have achieved. While Marx provided a powerful critique of capitalism, Babasaheb gave India something more valuable and enduring—a blueprint for social justice that works within democracy rather than against it.

In the battle between these two giants of thought, history shows that for India’s caste-oppressed, Ambedkar’s constitutional morality provides a more practical path to liberation than Marx’s revolutionary idealism.

Bodhi Ramteke is a lawyer, researcher, and Erasmus Mundus Human Rights Scholar enrolled at the University of Deusto, Spain. He tweets @bodhi_ramteke. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)