Before embarking on a journey, one must be clear of the destination. The journey is not an end in itself, but a means to an end. Nowhere is this truer than when it comes to the matter of conducting military operations as part of the grand strategy of a nation. If the ends — the desired aims or outcomes— are uncertain or ill-defined, then there is every possibility of getting bogged down in a never-ending and unwinnable battle.

In military appreciations, this boils down to the Ends-Ways-Means template. The end, or aim, is a military or politico-military objective aligned with a political aim. The means, or resources, are well-known and finite, and automatically limit the scope of the aim. The various ways to achieve the end, then, lie in the realm of strategy, and are also limited by various political and humanitarian considerations. This template is a dynamic one and determines the courses of action a nation might adopt in pursuit of its national interest or as a response to any threat to its territorial integrity or sovereignty.

What is important to note, though, is that irrespective of the chosen course, there must always be an exit strategy, should things not go according to plan.

Also Read: Hamas attack shows human intelligence is crucial for national security. Tech doesn’t catch intent

Wars with an end, and those without

In 1971, faced with the depredations and atrocities of the Pakistan Army, millions of refugees from erstwhile East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) poured into India. However, the cost of housing and feeding these refugees, estimated at $700 million, threatened to cause a drain on the Indian economy.

The end, therefore, was to create conditions for the return of the refugees to their homeland. This could be achieved by peaceful political and diplomatic ways, but if not successful, the military option was also open, which ultimately, we had to resort to. The Indian Armed Forces succeeded in capturing the whole of East Pakistan, leading to the creation of a new nation, Bangladesh, where the displaced persons could return. However, even if the entirety of Bangladesh had not been successfully liberated, as long as sufficient swathes of territory were captured for the refugees to return to, the political aim would still have been achieved. There was, therefore, an inbuilt exit strategy or fallback option.

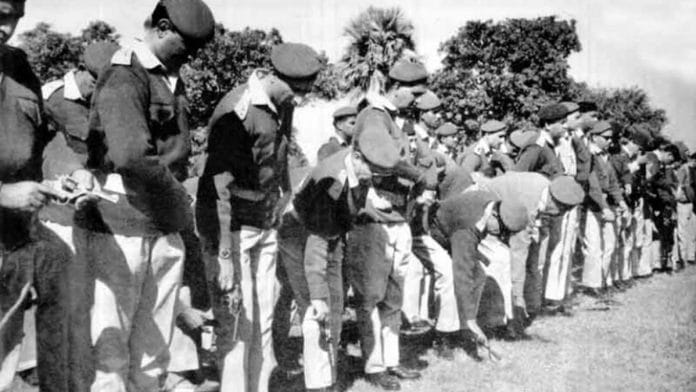

The Indian involvement in Sri Lanka from 1987 to 1990, a fallout of the Indo-Sri Lanka Peace Accord, was a totally different story. The Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) was sent to maintain the peace and act as a buffer between the Sri Lanka army and various Tamil militant groups. However, the IPKF soon found itself battling the very same groups it was sent in to protect. There was no clear-cut political or military aim and certainly no exit strategy. When the IPKF returned after suffering about 1,200 casualties, there was nothing to show for their efforts, neither in the political nor military arenas.

The two ongoing conflicts — the first between Ukraine and Russia, and the second between Israel and Hamas — show a similar lack of direction. What were Russia’s politico-military objectives and the envisioned end-state when it began its ‘special military operation’? Close to two years since the operation was launched in February 2022, it remains anybody’s guess. With the war at a stalemate, there does not seem to be any exit strategy on either side, except to throw more and more troops into battle – cannon fodder – in the vain hope of wearing the other side down. There seems to be a lack of strategic leadership in the reluctance to seek a face-saving compromise that would at least bring a temporary halt to hostilities.

The situation in Gaza is no different. What did Hamas hope to achieve by their blatant act of terrorism in Israel last month? Surely, they would have anticipated a disproportionate response. Or were they surprised by their own success? Retribution was swift in coming and Israel launched Operation Swords of Iron, using all the means at their disposal. Their response, considering the savagery of the Hamas attack, is understandable, but most of the victims are civilians caught in the crosshairs. It once again begs the question – what is the end-state for Operation Swords of Iron? Are there any intermediary stages which, if achieved, would give a notion of victory? Perhaps the unconditional release of all the hostages could pave the way for a truce.

Also Read: Defence expenditure is no ‘sunk cost’. It is a dangerous assumption to make

Don’t improvise, anticipate

There are many lessons to be learned as far as India is concerned. India is no stranger to brazen terrorist strikes and has responded appropriately when provoked. However, these responses were more to assuage public sentiment and did little to solve the problem per se. For instance, in June 2015, India launched Operation Hot Pursuit along the Myanmar-India border in response to the killing of 18 soldiers of the Indian Army in Manipur by terrorists of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland–Khaplang, or NSCN-K. The operation, which reportedly killed between 30 to 40 NSCN-K cadres, was a success, but Indian insurgent groups continue to thrive in camps in Myanmar.

Similarly, the Indian Air Force launched Operation Bandar, pre-emptive air strikes on terrorist training infrastructure in Pakistan’s Balakot, as a response to the February 2019 Pulwama terrorist attack in which 40 CRPF personnel were killed.

Quite like the current Israeli operation, this response was necessitated due to the sheer number of casualties, as it was a stab to our collective consciousness. Something had to be done. The Air Force rose to the occasion, but what was achieved in the long run is unclear. Would our response have been the same if the deaths had been three or four, part of routine operations, as continue to occur even now? And did our response solve the problem, or was it just a knee-jerk reaction to a grave provocation?

India is likely to face many such provocations in the future, across all dimensions – land, sea, and air. This was starkly brought out by the hijacking of the India-bound, Japanese-operated ship Galaxy Leader by Houthi terrorists in the Red Sea on 19 November.

The need of the hour, therefore, is for India to be able to anticipate likely threats and plan, prepare, and rehearse its responses rather than improvise after an incident has occurred. The latter approach runs the risk of India getting sucked into an escalating spiral of violence. A swift, punitive, targeted strike will have much greater impact than a larger, long-drawn operation weeks or months later.

General Manoj Mukund Naravane PVSM AVSM SM VSM is a retired Indian Army General who served as the 28th Chief of the Army Staff. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)