Gone are the days when practices attached with religions other than ours excited us. Now they scare us.

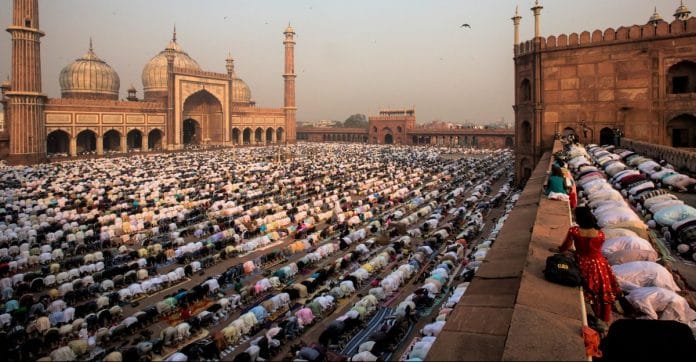

“Suddenly, the Eidgah came in sight. The thick shade of a tamarind tree above, below a jajam spread out on a pucca floor. Row after row of rozadars stretching far beyond, where there is no jajam even. No one bothers about wealth or position here. Everyone is equal in the eyes of Islam. How beautifully it is managed and organised. Thousands of heads bow together and then rise to their feet together, like thousands of electric bulbs lighting up together and then dimming together. What an exceptional sight it presents with its collective actions and unending expanse – filling the heart with reverence, pride and inner joy. As if one single thread of brotherhood connects all those souls, creating an unbroken chain.”

This was Hindi writer Munshi Premchand observing namazis in ‘Eidgah’. It kindles the poet in the otherwise realist and prosaic Premchand, and is a rare passage in his oeuvre.

His contemporary, the poet and politician Sarojini Naidu, also felt enthralled by the sight of namaz in her 1917 talk titled ‘Ideals Of Islam’: “The democracy of Islam is embodied five times a day when the peasant and the king kneel side by side and proclaim, ‘God alone is great’. I have been struck over and over again by this indivisible unity of Islam that makes a man instinctively a brother. It was this great feeling of Brotherhood, this great sense of human justice, that was the gift of Akbar’s rule to India; because he was not only Akbar the great Moghul, but Akbar the great Mussalman: that he realised that one might conquer a country, but that one must not dishonour those whom one conquered.”

Both the writer from Uttar Pradesh and the politician from Hyderabad felt drawn to the “other-religionists” by the sight of namazis. Naidu underlines Akbar’s Muslimness, stresses that it is his Muslimness which gave India ‘salam’, the symbol of peace.

Compare these examples of the exalted language of Premchand and Naidu with the derision that drips from the words of the chief minister of the state Premchand belonged to, when he mocked Rahul Gandhi for sitting like a namazi in a temple. Omar Abdullah had to tell him that Muslims do not sit while offering namaz. In namaz, bodies are in perpetual motion.

What a distance we have covered in these 70 years! What a fall!

There was a time when we had a leader like Mahatma Gandhi who could say that even if he forgot the Gita and remembered only ‘The Sermon on the Mount’, he would derive the same spiritual delight from it.

Gone are the days when practices attached with religions other than ours excited us. Now they scare us.

Premchand and Naidu came to mind when worshippers participating in collective Jumma namaz were attacked and their prayers disrupted in Gurugram last week. It is considered a sin for anyone to disrupt an act which is held sacred by people. But here it was done with pride, as if the disrupters were on a spiritual mission.

Hindus of Gurugram are being told that the collectivity of Fridays is a threat to them, that it is a show of strength by Muslims. In fact, our Hindu friends need to just be there to observe the gathering of worshippers, to absorb the serenity of the moment, to see how peacefully the namazis gather and disperse.

The summer sun would now turn harsher. The namazis in the open would have no shade. Let us be there before Ramzan sets in, with water to help them wet their parched throats. Watch as the namazis brave the heat and gather during Ramzan.

The words of Rabindranath Tagore, published in Poetry magazine 1912, capture the spirit of this solitude in multitude: “Oh! Grant me my prayer, that I may never lose the touch of the one in the play of the many.”

It would be unfortunate if Gurugram and the rest of India prefer to alienate themselves from that ‘touch of the one in the play of the many’.

Apoorvanand teaches Hindi at Delhi University.

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ें: खट्टर की टिप्पणी के बाद ज़रा याद करें नमाज़ियों के लिए क्या कह गए सरोजिनी नायडू और प्रेमचंद