The Aam Aadmi Party took only a decade to enter the prestigious club of national parties. Only nine political parties have this distinction in India today. The AAP was founded in 2012. Now it has two state governments in its kitty and a presence in many state assemblies. It has no Lok Sabha MP presently. Despite that, its ascent is spectacular by any extent.

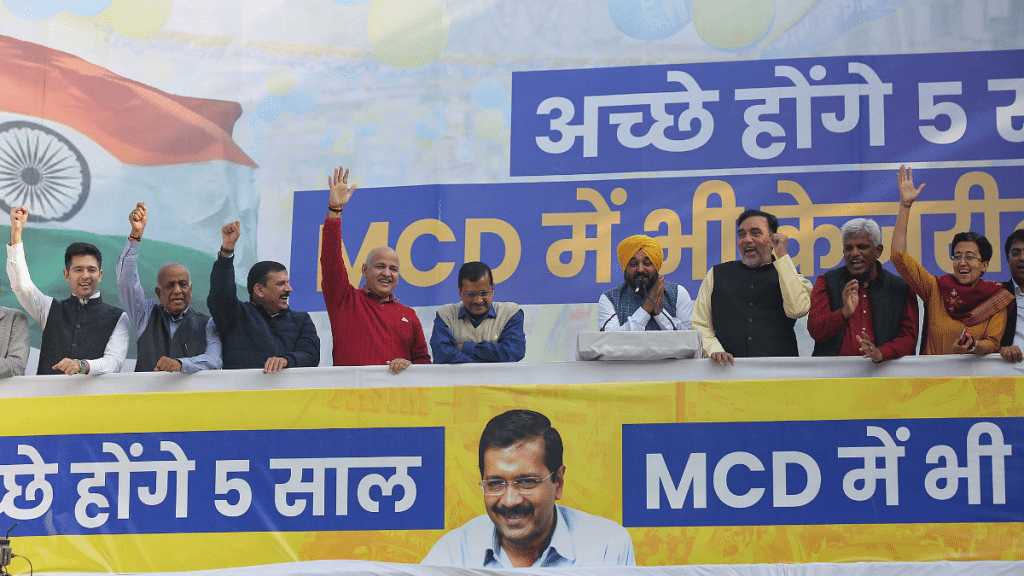

It’s true that 2022 has been a watershed year for the AAP. It won in Punjab and defeated the BJP in the municipal elections in Delhi. There are debates in media asking can AAP become the main opponent of the BJP in national politics and can it be Modi vs. Kejriwal grand battle in 2024 Lok Sabha elections?

But I argue that the AAP has now reached its peak. From this point on, it will be a downward journey for the party.

Apoliticism or being above dirty politics was considered to be its biggest strength at one point. But in a decade-old journey, the AAP has metamorphosed into just another party, rather just another Hindutva party, even if of a lighter hue. At least one pollster is saying that AAP’s support among the Dalits and the Muslims is on decline in Delhi. I don’t think that there is space for two Hindutva parties in the Indian political arena. And the BJP being more diverse of these two will definitely edge out the AAP in electoral battles.

Moreover, after the Satyender Jain episode and the alleged Delhi liquor scam cases, we can say that the AAP also failed to be different on account of corruption and propriety in politics. Kejriwal started his political journey in a blue WagonR. Now he is using a long cavalcade, like any other big politician. It has proved to be just like so many other political parties. Free electricity and other similar promises have ceased to be a differentiator. I have seen the election campaign of AAP and I can vouch that the party is a cash-rich organisation—it spends a whole lot of money in electioneering. There is nothing unique about the AAP now.

Despite tall claims, the AAP won only five assembly seats in Gujarat. It fared more miserably in Himachal Pradesh. Earlier, it failed in Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Bihar. In the next six months, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Telangana, Tripura, Meghalaya and Nagaland are going to polls. I don’t see the APP gaining much ground in these states either.

Also read: AAP’s ‘double-engine’ win in Delhi is no cause for celebration. TMC example shows why

Replicating success a tough task now

The AAP was formed during UPA-2. It started as a movement against corruption in politics and later took the shape of a populist centrist political party that promised to change the way politics is done in India. But replicating its victory in other states is going to be a difficult task.

The biggest problem with the AAP is that it is no more an apolitical organisation. A large section of the Indian urban middle class has apathy for the political process. I hate party politics is a common refrain in urban spaces. The AAP cashed on it and projected itself as a party of apolitical, righteous, honest persons. It claimed to cleanse the politics and weed out corruption and dishonesty. In its initial days, it took middle ground on most of the contentious issues and policies. We still don’t know about AAP’s position on economy, defence, agriculture, criminal justice system or foreign policy. We don’t know what the AAP’s take on reservation policy or communalism or taxation is. It doesn’t have a take on India’s language policy either.

As an opposition, a party can remain silent on different issues. Such ambiguity is certainly not immoral. But as a ruling party, taking the middle path is not always a valid option. Even not taking a position or remaining absent in the House when voting on crucial issues is on, qualifies as taking a position—lower participation impacts the outcome of voting.

Also read: Gujarat makes AAP a national party, but Arvind Kejriwal is no Jayaprakash Narayan

Two BJPs

The AAP was exposed when forced to take position on important Bills and decisions of the Narendra Modi government. It supported BJP on Ram temple, abrogation of Article 370, and tried to steer clear of the CAA protests. Even during the 2020 Delhi riots, the party decided to remain mum and didn’t mobilise its leaders and workers to form peace committees or ask them to put efforts to stop the violence engulfing the national capital. Recently, during Gujarat elections, Kejriwal demanded to put pictures of Laxmi-Ganesha on the currency notes and thereby tried to create a more kattar Hindu image for himself and his party.

By doing so, the AAP came closer to the BJP on ideological spectrum. The question is, is there enough space in the politics for two BJPs? Political researcher Asim Ali provides an interesting thesis — “the AAP provides a middle ground pitch: Right-leaning voters can vote for their populist promises, without compromising on their ideology.” It seems that the APP is faltering in this balancing act. Placating the Right-leaning Hindu voters is perhaps creating tension among the Muslim voters.

In the recent the Municipal Corporation of Delhi elections, the AAP lost in many of the Muslim-dominated seats. It fared badly in those areas of North East Delhi where as many as 38 Muslims had lost their lives during 2020 riots. The Congress won Brijpuri, Shastri Park, Chauhan Banger and Mustafabad constituencies in these areas. The AAP also lost Abul Fazal Enclave, which includes Shaheen Bagh, and Zakir Nagar. It seems that Muslim support for the AAP is declining in Delhi. These areas were considered AAP strongholds.

Silence on caste inequality

Similarly, the AAP is going neutral on caste fault lines and trying to garner votes from all sections of society. It has positioned itself as a party of continuity and status quo as far as social structure is concerned. It neither supports, nor opposes reservations. But the status quo does not suit the interests of the underclass and lower caste groups. They want change. The AAP cannot afford to destabilise the social structure as it may antagonise the upper caste elites. So, it has steered clear of challenging the caste hierarchies. Instead of doing any substantial work, the party offered symbolism to the Dalits and other lower castes. This is why the AAP leaders, including Kejriwal and Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann, put too much emphasis on hanging portraits of B.R. Ambedkar in their offices and residences.

Like many Rightist/conservative parties of the West, the AAP also gets its support from the middle class and poorer sections of society. The party spends some government money on schemes to placate the underclass and at the same time ensures that interests of the elites are not harmed. The AAP is spending money to improve school infrastructure but at the same time, two-third of Delhi’s higher secondary schools are not offering science subjects. Medium of imparting education in Delhi government schools remains vernacular. Thus, the AAP’s education reform in Delhi is not changing the present social order.

It’s not that other parties are doing something radical on these counts. But the AAP, by doing run-of-the-mill politics is breaking the promises it made to the people. It is increasingly looking like a replica of the BJP sans its historical legacy. The party’s leadership is predominantly upper caste male and it is providing nothing new or unique to the masses. It’s astonishing that the Kejriwal cabinet does not have any woman minister.

Dilip Mandal is the former managing editor of India Today Hindi Magazine, and has authored books on media and sociology. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)