On 15 March 1950, the Union Cabinet passed a resolution declaring that “the need for comprehensive planning based on… an objective analysis of all the relevant economic factors has become imperative.” The result was the creation of the Planning Commission. It was not just an administrative body, but the culmination of an intellectual and political movement that started in the early 1930s, gained momentum in the 1940s, and helped steer India’s political economy for the next five decades.

However, when it was dismantled in 2014, critics saw the move as a belated course correction—one that, in their view, should have occurred in 1991. Or better yet, they held, the Planning Commission (PC) should have never been created at all.

To understand why India embraced planning, we must understand the ideas that shaped the independence movement. In 1950, planning was not a foregone conclusion—it was a deliberate choice. Across the political spectrum, from the Socialists to the Communists to the Hindu Right, and even businesses, planning was viewed as critical in shaping India’s economic destiny. Amid the tumult of WW1, the Great Depression, the Russian Revolution, and WW2, state-led intervention appeared to provide much-needed social or economic stability. This was seen as crucial for avoiding further wars and revolutions. In the Indian context, it was a way to hold a fragmented, impoverished country together following the trauma of colonialism and Partition.

Today, with the world economy becoming increasingly fragmented and the emergence of great power rivalries, states are taking a more proactive role in economic affairs. So it is imperative to ask why India embraced a planned economy in 1950, and how that continues to shape its future.

Global consensus in the 1930s

By the late 1930s, the Great Depression had shattered faith in free markets. British economist John Maynard Keynes showed that governments could—and perhaps would be forced to—intervene in order to pull economies out of collapse.

Across the world, various forms of planning became a tool of reconstruction, from Roosevelt’s New Deal in the US to the Beveridge Report in England and the larger postwar development plans in Europe. There was a broad consensus that unregulated markets produced disorder, not stability. This sentiment was later echoed by Indian business leaders in 1944 and 1947, when India was on the cusp of Independence.

The USSR’s centralised planned economy offered a more radical yet appealing model. Jawaharlal Nehru’s 1927 visit to the USSR left a deep impression on him.

He wrote admiringly that its Five-Year Plans had ushered “a new sense of economic security among the people [of the USSR],” and that Russia, “a feudal country…has suddenly become an advanced industrial country.” (Glimpses of World History, 1934, p 995) To him, this approach helped overcome class barriers. He observed that the Moscow opera “was full with people in their work-a-day attire.” The trip left Nehru with the impression that state intervention and planning could actually result in transformative outcomes.

Also read: Trump is treating diplomacy like a failed casino deal

Economic ideas in the Congress party

The British Raj left India fractured, impoverished, and institutionally underdeveloped. It had few large-scale industrialists, no unified market, and vast disparities across caste, class, and region. In such a context, planning served both economic and nation-building purposes. It allowed the Indian state to articulate developmental priorities, direct investment, and unify a fragmented country under a common vision. For a country with weak private capital and sharp social cleavages, the state became the default engine of growth and coordination.

The 1931 Karachi Congress resolution called for state control of “key industries and services, mineral resources, railways, shipping, and other means of public transport.” In his 1936 presidential address at Faizpur, Nehru argued that “only a great planned system for the whole land and dealing with all these various national activities [land reforms, industrial growth, cottage industries]” could offer a solution to India’s economic challenges.

In 1938, the Congress, under Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, established the National Planning Committee (NPC). Though its proposals were only adopted in a few provinces like Bihar and UP, and the committee was disbanded in 1939 after Congress ministries resigned, the NPC laid crucial intellectual groundwork for post-independence planning. Notably, it included prominent intellectuals like Professor KT Shah, Gulzarilal Nanda, and business leaders such as Purshottamdas Thakurdas. And Thakurdas, along with other doyens of Indian industry like JRD Tata, GD Birla, and Ardeshir Shroff, continued to support planning as a stabilising framework for industrial growth through the Bombay Plan.

Also read: L&T exit aside, Bengaluru’s suburban rail dream faces another big hurdle—shinier big-ticket projects

Economic ideas in modern India

Planning was embraced across the Indian political spectrum due to a desire for independence. This was also coupled with the desire to mobilise India’s limited resources effectively, to ensure economic growth for the entire nation, and to check worsening inequality. One article introduced in the Constituent Assembly proposed eliminating the profit motive in production. Another sought to give workers control over the state’s administrative machinery. While both were rejected, it is clear that disagreements were not about whether the state should direct the economy, but about the degree and form of that intervention.

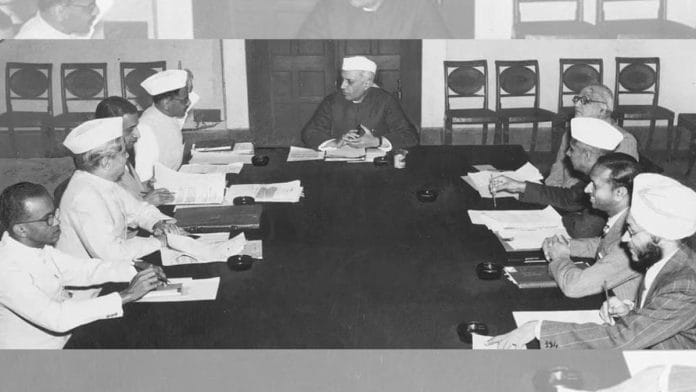

The compromise that came about finally was a semi-planned economy aimed at alleviating poverty and making India self-sufficient as well as bereft of foreign influence. The PC’s setup was unique: it was a semi-independent institution housed, contrary to most expectations, outside the finance ministry, but nonetheless was not a Union ministry either. Nehru, Nanda, and PC Mahalanobis were among the many crucial figures who shaped the initial activities of the PC. Nanda, who had a background in labour economics and cooperatives through the freedom struggle, became the first Deputy Commissioner of the PC. He helped build the institution itself—hiring its early staff, drafting operating procedures, and promoting coordination with state governments. He saw planning not just as technocratic governance, but as a means to mobilise national unity through administration.

Nehru provided the PC with patronage and cover to operate. As Chairperson, he helped cement its importance in the state apparatus. Even then, as Nikhil Menon notes in Planning Democracy (2022), it was not an all-powerful body as commonly believed. It merely helped translate an intellectual moment into some form of reality.

The first Five-Year Plan (FYP) focused on stabilising India’s food security and establishing technical institutions needed to grow India’s economy. The second FYP marked a leftward shift in India’s economic discourse with Mahalanobis’ views. A renowned statistician, he brought Soviet-style modelling to Indian economic planning and believed that industrialisation could not be left to market forces, especially in a capital-scarce economy like India’s.

In Mahalanobis’ framework, the state had to direct investment toward sectors that would yield the greatest long-term returns—chief among them, heavy industry and capital goods. This called for massive public investment in steel, machine tools, and infrastructure. While the plan was heavily criticised later for underestimating consumer demand, agricultural constraints, and capital restrictions, the Mahalanobis model embodied the core developmental belief of the era: that self-reliance was an essential path to economic freedom.

Regardless of the outcomes of the planned economy, it served as an integral framework that shaped India in the initial years of independence.

In 1991, India’s economy was flailing under this regime, forcing it to be opened up to the rest of the world. Since then, it has grown rapidly and expanded opportunities for many. However, recent production-linked incentives (PLI), infrastructure pushes, and public capital formation suggest that the state has begun reasserting its powers in the economy. This is further compounded by the rerouting of supply chains away from China toward India and other emerging economies.

As industrial policy, public investment, and state-led development return to the global stage, India’s early experiments with planning offer perspectives on the role of the state in the economy, and offer ways to manage such radical transformations and global turmoil. The future may not lie in replicating the model, but we cannot understand the present without reckoning with its intellectual legacy.

Vibhav Mariwala writes about political economy, history, and the institutions that shape our world. He works on public policy and global macro between London and Mumbai and tweets @VibhavMariwala. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

All are utter-flop socialist plans of economics quack J Nehru. We remained Asian beggars while Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, & Singapore became developed countries after embracing free markets.