A large section of Indian farmers have been protesting against the new farm laws over the past six months. Over the past few decades, farmers have taken to the streets in some part of the country or the other every few years, on a range of issues. But one thread that has remained constant, and has grown larger over the past couple of decades, is that of farmers’ suicide.

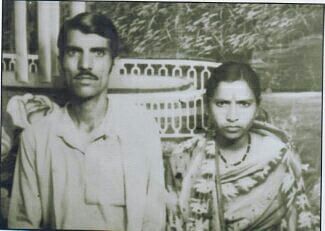

Thirty-five years ago, it was on 19 March 1986 that the first mass suicide by a farmer’s family in Yavatmal district was recorded. Sahebrao Karpe Patil, a farmer, a former panchayat member of Chil Gavhan village (Yavatmal district, Maharashtra) had committed suicide along with his wife and four children. The family had travelled from what was then a relatively remote village in Yavatmal to Pavanar in nearby Wardha district, where Vinoba Bhave’s Ashram is located. The farmer couple committed suicide by consuming pesticide, first feeding their children the poisonous food.

On Delhi’s borders, over 250 farmers associated with the ongoing agitation are said to have lost their lives over the past few months. Quite a few of them are said to have committed suicide, others died due to exposure to harsh winter, illnesses and accidents.

Also read: Efforts being made to remove barriers in farmers’ journey from seed to market, says PM Modi

What the data tells

According to official statistics, over 10,000 farmers and others dependent on agriculture choose to end their lives each year for a variety of reasons — monetary, social or health related. Of these, about half are actual cultivators, most of whom reportedly commit suicide due to farm distress, caused by crop failure and the consequent debt burden.

The tragedy cuts across political differences and policy debates. Inevitably, the data have got politicised, with the state and central governments often feeling compelled to claim that their policies are making a positive difference. But organs of the State remain typically reluctant to recognise the tragedies as they occur, and often delay the publication of “sensitive” data.

According to the latest Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India report 2019, published by the National Crime Records Bureau last year, 10,281 people dependent on agriculture committed suicide. Some may argue that with almost 50 per cent of the population dependent on agriculture, only 7.4 per cent of the total number of 139,516 suicides in the country are among the farmers. Although, this would amount to an average of around 28 farmers deciding to end their lives every single day.

Others note that with 50 per cent of the population dependent on much less than 20 per cent of GDP that comes from agriculture, the sector is tethered to poverty and distress. That the number of farmers’ suicide is not in proportion to the share of the population in agriculture is a reflection of the extremely hardy nature of farming communities. No section of the people take the kind of risk farmers take every time they sow a crop and nurture it over a few months, not knowing if at the end of the day the crop will survive, or if she/he will get a remunerative price for the crop.

During the budget session of Parliament in February, the Narendra Modi government informed the House that 5,957 farmers committed suicide in India in 2019 as compared to 5,763 in 2018. Maharashtra contributed nearly 45 per cent of all farmer suicides, followed by Karnataka (22 per cent). This would mean about two deaths every three hours. The government has clarified that the data is incomplete since many states have not provided the break-up of the causes of deaths.

While statistics may tell their own story, each death is a tragedy, and this is a continuing one.

Just this month, Chhattisgarh was in political turmoil following the death of five members of a farmer’s family. The five were found dead in their home in Bathena village, five kilometres outside Durg on 7 March 2021. The police too seems to be at odds in explaining the exact reason for the mass suicide. The burden of debt being possibly the key factor.

Also read: There would have been no protest had govt consulted farmers on agri laws — UP BJP minister

The suicide of 1986

Suman Agrawal, an activist of the Shetkari Saghtna (farmer’s association), was on a tour of villages in Wardha district of Maharashtra in March 1986 when she came to know of the mass suicide of a farmers’ family. Agarwal had recounted the tragic event to The Indian Express in 2019. On hearing the news of the death of a farmer and his family, she had rushed to Duttapur village near Wardha. “Six bodies lay on the floor of a hut, with a Re 1 coin placed on the heads of five of them. Four were children — the youngest, a girl, no more than eight months old. Next to them was their mother. A few feet away lay the father, who had killed his entire family before consuming poison.”

Karpe’s family farmed on 20 acres of land. Due to financial distress, the family had already sold half their land. Then in 1985, his crop was lost. He was burdened with debt. The electricity board apparently threatened to cut off supply. Fearing the loss of his standing crop, and unable to bear the strain, the family decided to end their lives. Perhaps sensing that their deaths in their remote village may not be recognised, they decided to travel to Wardha.

Three decades after this tragedy, Kisan Putra Andolan, a relatively young grassroots movement in Maharashtra decided to remember this day, and all the other farmers who have since given up on their lives. Amar Habib, the coordinator of the Andolan, a former journalist based in Beed district, held a day-long fast at Karpe’s home in Yavatmal on 19 March 2017. Since then, each year, the Andolan invites farmers and others concerned with agricultural distress to fast for 12 hours, individually at home, or collectively where possible.

Habib told the Outlook magazine in 2019 that Sahebrao Karpe had written a detailed a note on farmers’ distress. “He wrote a detailed note urging authorities to focus on problems of farmers. Karpe, who owned adequate land and a big dilapidated house, was driven to such an extreme step because of crop loss and the inability to repay debt. Though the suicide created an uproar, it failed to create the right policies. In fact, thousands of farmers have taken their lives in the coming years. While working on the subject of farmers’ suicides and trying to identify the true cause behind this distress, I remembered the first suicide and decided I should shun food on this day to pay tribute to Karpe and his family and express solidarity to farmers.”

Indians today are divided along many lines of caste, community, language, region, as well as politics. Farmers too are divided along those lines and on agriculture policies. Between 1995 and 2016, more than three lakh farmers died by suicide, according to the NCRB data. Farmers who committed suicide over the past few decades perhaps also reflected those divisions during their life. But these deaths may not yet be in vain, if the farmers and the country could come together, at least for a day, to recognise this continuing loss, and spare some thoughts on possible ways to avoid these recurring tragedies.

In these polarised times, with opinions sharply divided on the way forward to address farm distress, 19 March could well become a day to pause, to come together as citizens and farmers. That itself may help sow the seeds for a better tomorrow.

Also read: Marked change in Mamata’s manifesto amid BJP surge, CM promises slew of direct cash schemes

The paradoxes

A pause may help recognise one of the real paradoxes of Indian agriculture. Indian farmers today are victims of their success, having turned the country around from being a food deficient to food surplus one, with nearly $40 billion in agricultural exports. Rather than villains wallowing in subsidies, Indian agriculture is the last bastion of social support for millions. Of the tens of millions of migrant workers who returned to their villages during the lockdown, many have stayed back to cultivate land in search of food security rather than the uncertainty of again joining as the urban wage labour. Indian farmers are often accused of enjoying tax-free status, but by manipulating prices and trade policies, the producer support estimate has been negative for decades. In effect farmers are being taxed, while a lot of the farm subsidies are actually going to corporate India providing various inputs.

A reflection on farmers’ suicide may help realise that the real crisis facing India is not really in agriculture, but in the non-agriculture sector. This is preventing millions who are eagerly looking for economic and employment opportunities outside of agriculture from moving out. Indian farmers, the largest private sector in India, have performed a miracle. It is the so-called organised sector of India’s economy that has consistently failed to keep up with the changing socio-economic dynamics of Indian agriculture.

Irrespective of what one may think of the new farm laws, they do provide an opportunity to ponder over the real challenges facing the country. And that may help in developing a shared perspective on the kind of reforms agriculture really needs, rather than the usual divisive rhetoric.

The author is an independent commentator and a long time proponent of market reforms, with a particular interest in agriculture policies. Views are personal.

All of these at these at the borders Shinghu and punjab are just impostors none of them are farmers. So no sympathy is required .

Since the last 35 years, no farm leader from Punjab bother to visit the family of the deceased farmer in other states of India.