Was the 2024 election result a mandate for democratic and secular India? We conclude our six-part analysis of an extraordinary election outcome by addressing this all-important question.

In one sense, the answer is an obvious yes. This election was a referendum on the Supreme Leader. Narendra Modi had asked for an unqualified public endorsement for his authoritarian rule of the last ten years and for the dismantling of the republic in the next five. The people of India refused to put their stamp of approval on this design. Despite Modi’s desperate anti-Muslim vitriolic, the communal appeal did not trump over everything else in the heartland of Hindu majoritarian politics. This outcome is a personal defeat for the Prime Minister that punctures his image of invincibility.

Some consequences are obvious: India’s democratic backsliding, from a competitive authoritarian rule to pure authoritarian state, has been halted. Democratic spaces have opened up—both within the BJP, and inside and outside the Parliament. Brakes have been applied on the ideological project of mutilating the constitutional vision of secularism in favour of a Hindu majoritarian state.

All this is critical, but not sufficient to call this a mandate for democratic and secular India. That’s because these are the consequences of the verdict, not necessarily the intentions of the voters. Much of the analysis of the 2024 election is based upon inferences drawn from the overall outcome. We don’t know how valid these inferences are until we can read the voters’ mind.

Fortunately, we now have a direct way to verify this. The Lokniti-CSDS has just released the findings of their post-poll survey (based on face-to-face interview of a random sample of nearly 20,000 voters after polling, but before counting), something they have done for every Lok Sabha election in the last thirty years. [Disclosure: Two of us have been part of the CSDS-Lokniti team in the past, but have no association with this survey]

Unlike the usual exit polls that are limited to finding out voting behaviour and social background, this study quizzes the citizens about their opinions and attitudes as well. While we wait for a detailed and nuanced analysis of this data by the scholars associated with the CSDS-Lokniti network, we can draw some broad conclusions from the information currently available in the public domain.

(Note that for all the survey questions, we have included only those respondents who have expressed an opinion and excluded the ‘No Response’ and ‘Don’t Know’ from the analysis)

Democratic habits of mind

Turning first to democracy, one thing is clear: Seven decades of functioning democracy have inculcated democratic habits of mind that are not easy to bulldoze. In its most basic form, an average Indian (46 percent in this survey) identifies democracy with the opportunity to change a government through free and fair elections. Given the context of this survey, it is noteworthy that almost two out of three people who express an opinion believe that regular change of government is more conducive to development rather than a single party continuing for a long time.

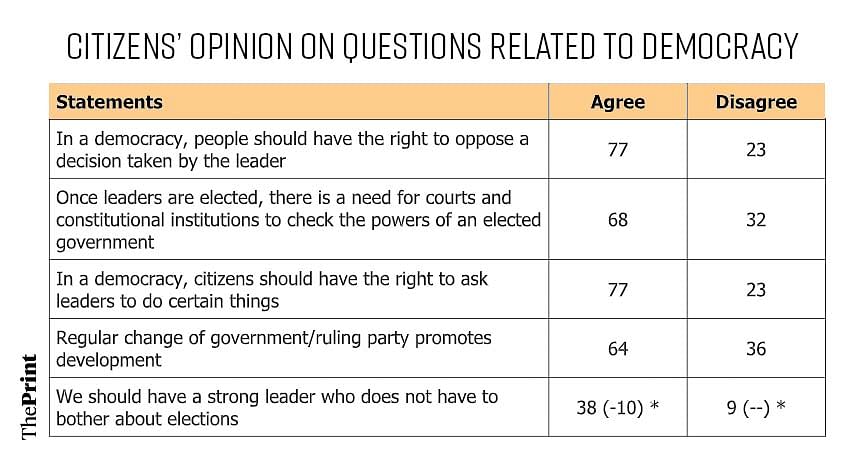

Table 1: Democratic sentiment remains robust, people dislike unfettered rule

Note: All figures rounded off. Percentages calculated from among respondents who gave their opinion. ‘No Opinion’ set as missing *Figures are only for ‘Fully Agree’ and ‘Fully Disagree’ categories. Figures in parentheses denote percentage point change since 2019. Question was also asked back then.

Support for democracy is not limited to the ability to change the government through elections. The Indian voter also supports an idea which is an anathema to the Modi government – checks on the democratically elected rulers. An overwhelming majority of the voters, 77 per cent, uphold the idea that in a democracy, people have the right to influence and even interfere in their leaders’ decision-making. In what can be construed as an indictment of the present government, the same proportion supports peoples’ right to dissent if the government’s decisions are not to their liking. No less important is the endorsement of the idea of constitutional checks and balances: 68 percent believe it is necessary for courts and constitutional institutions to check the powers of an elected government. Indian voters may not possess the language of liberal democracy, but they are certainly not willing to accept arbitrary, unaccountable, and unchecked rule.

While celebrating this democratic inclination, we must not forget that just one out of four respondents reject a classic soft-authoritarian suggestion, “We should have a strong leader who does not have to bother about elections”: more than a third ‘Fully agree’ with it and another third ‘Somewhat Agree.’ But, we can take solace that compared to 2019, the proportion of people who ‘Fully Agree’ has decreased by 10 percentage points (pp) and those who overall ‘Disagree’ has increased by 2 pp. While the Modi government turned towards authoritarianism, the people moved in the opposite direction.

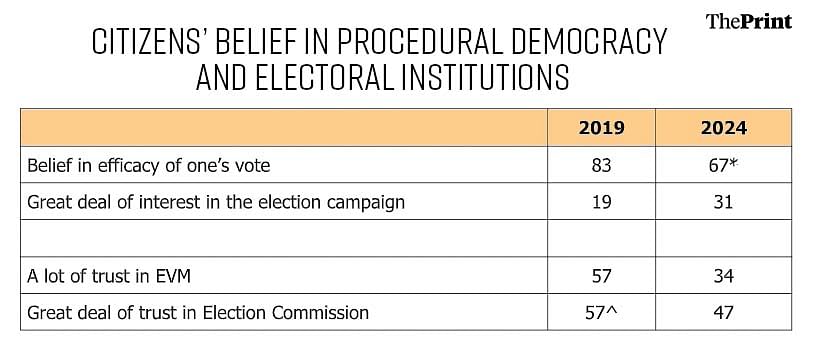

The last five years have also accentuated democratic anxiety. Only 67 percent of people said their vote makes a difference. This is the lowest-ever recorded level of democratic efficacy in the last five decades of survey research in India. The high level of trust needed in the electoral process has also come down. Compared to 2019, the proportion of those who report high levels of trust in the Election Commission of India is down from 57 percent to 47 percent; similarly, the proportion of people with a ‘lot of trust in the EVM’ is down from 57 percent to 34 percent. We can only hope that the 2024 election outcome has enhanced citizens’ sense of efficacy in their vote and restored their trust in the working of the EVMs.

Table 2: Faith in the electoral process and institutions has declined

Note: All figures rounded off. Percentages calculated from among respondents who gave their opinion. ‘No Opinion’ set as missing. *Unlike 2019, CSDS asked the efficacy of vote question in their pre-poll study this time. ^In 2019, the question on trust in the Election Commission was worded slightly differently. It was about trust in its “fairness in conducting elections”.

We do not yet know if the people held the Modi government responsible for the violation of these basic democratic norms and punished it. Sadly, the survey does not probe this angle very much. We do know, however, that people disapproved of the arrest of opposition leaders just before elections: for every one person who claimed that these politicians had been arrested because they were more corrupt than their BJP counterparts, almost two believed that corruption was not the issue: the leaders had been arrested for purely political reasons.

When asked to name the things people dislike about Mr. Modi’s BJP government, 0.8 percent mentioned ‘Dictatorial government’. When asked to name why they would not want to give his government another chance, 1.1 percent mentioned ‘intolerance, curtailment of civil liberties.’ These might be small numbers, but we have already shown that this election was decided by small numbers.

Cooling down of majoritarianism

Unlike democracy, the evidence is mixed on attitudes toward secularism. This is hardly surprising. Professor Suhas Palshikar has repeatedly illustrated how the BJP has managed to shift the entire spectrum of public opinion in favour of majoritarianism. One should not expect a pendulum swing in an election where the Supreme Leader launched an unbridled assault on the idea of minority rights. But this survey registers subtle shifts that puncture the claims and hopes of the BJP and the RSS. While 22 percent mentioned the consecration of the Ram temple in Ayodhya as the action they liked the most about the Modi government, only 5 percent of all voters singled this out as the reason to give the BJP another chance. In all likelihood, the Ram temple gave BJP faithfuls a reason to stay with the party and rationalise their political choice. But it does not appear to have shifted votes toward the BJP.

We know from the pre-poll survey by Lokniti-CSDS that there is near unanimity about the abstract idea of an inclusive India; contrary to the ghuspaithia (infiltrator) narrative unleashed by the Prime Minister. For every one person who agrees with the statement “India belongs only to Hindus”, there are more than seven who agree that “India belongs to citizens of all religions equally, not just Hindus.”

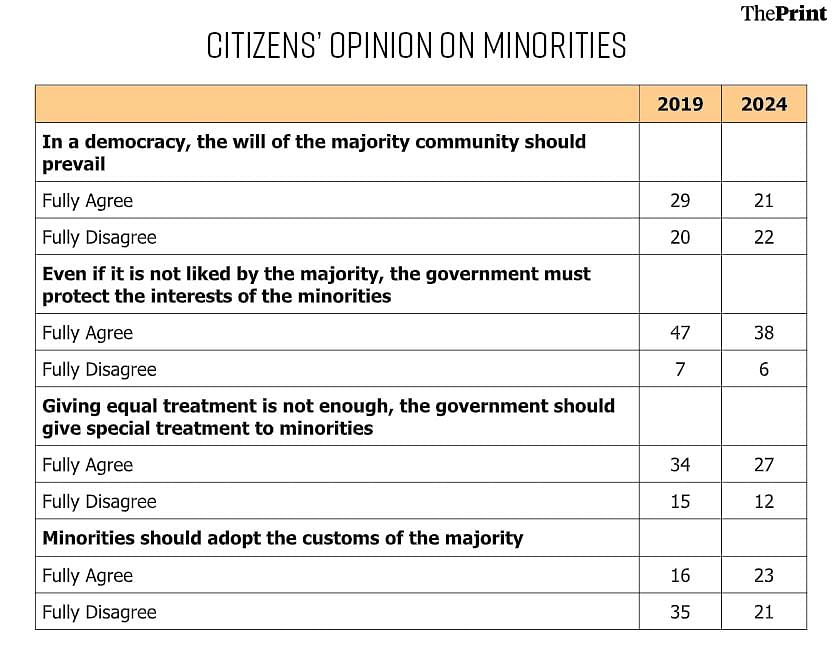

The post-poll survey records a small but critical shift away from majoritarianism in its concrete manifestations. Compared to 2019, more voters ‘Fully Disagree’ with the classic majoritarian statement: ‘In a democracy, the will of the majority community should prevail’. To be sure, the proportion of people who agree with the statement is much higher than it was in 2004 or 2009, but a more recent comparison can be 2014. In 2014, on the back of the ‘Modi wave’, the proportion of those who ‘Fully agreed’ with this statement was 40 percent. It came down to 29 percent in 2019 and has cooled down to 21 percent this time.

Table 3: Anti-minority rhetoric did not work as majoritarian sentiment has weakened

Note: All figures rounded off. Percentages calculated from among respondents who gave their opinion. ‘No Opinion’ set as missing; figures for moderate agreement and disagreement with the statements not shown here.

At the same time, we do not see a proportionate increase in the support for minority rights. The PM’s move to raise the temper on this issue may have had some impact here. Two decades ago, 67 percent fully agreed with the statement: ‘Even if it is not liked by the majority, the government must protect the interests of the minorities’. This proportion has steadily dropped after 2014 and has now declined to 38 percent. (However, if we include those who ‘Somewhat Agree’ with this statement, the proportion who overall agree is still well above three-fourths: the sensibility is yet widespread but the conviction has decreased)

In a similar vein, the proportion who ‘Fully Agree’ that the government should give not just equal treatment but special treatment to minorities has decreased from 34 percent in 2019 to 27 percent in 2024; on this, the proportion who ‘Fully Disagree’ has also decreased a bit. This moderation of opinions is not inconsequential in the context of attempts to polarise.

While there is moderation in the political dimension of majoritarianism, the pressure for cultural assimilation has increased. Between 2019 and now, the proportion of those who ‘Fully Agree’ that ‘Minorities should adopt the customs of the majority’ has gone up by 7 percentage points. For the first time since 2004, when this question was first posed, has the proportion of Indians who ‘Fully Agree’ or ‘Somewhat Agree’ with this statement exceeded those who ‘Fully Disagree’ or ‘Somewhat Disagree’ with it.

All things considered, this may not amount to a ringing endorsement of the ideal of secularism. It would be a mistake to read back the political impact of the 2024 verdict into the minds of the voters. But it is fair to conclude that the Indian voters have not been blown off their feet by the strongest majoritarian storm yet.

The evidence presented above is by no means a guarantee for the future of a democratic and secular India, but it does provide enough ground to build a politics to reclaim the spirit of our republic. You cannot expect more than that from one election, especially the one designed to dismantle the idea of India.

Yogendra Yadav is National Convener of the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. He tweets @_YogendraYadav. Shreyas Sardesai is a survey researcher associated with the Bharat Jodo Abhiyan. Rahul Shastri is a researcher. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)

Secularism, as practiced in India, is nothing but naked minority, particularly Muslim, appeasement. It is dog whistle to confine Hindus to second class status in India. BJP/RSS is coming in the way of this woke project.

Contrary to the popular belief that there is this fear in minority so they must be protected, the opposite is true: the majority must be kept fearless and calm. This misconception of protecting minority is present not just in India but across the world, and throughout all times.

The fear in the minds of majority is prior to that of minority, always and everywhere. The fear always first develops in the minds of majority that they might lose their dominance, identity, culture, wealth etc. And in a stable society, the minority usually have nothing much to lose as in most cases they already develop some kind of mutual acceptance and even agreement to some authority of the majority. This keeps the society balanced and caring. But, due of some political or economic changing conditions, this natural balance gets disturbed. Doubts and fear start building and remain latent in the minds of the majority, and if remain unaddressed or aggravated for some ulterior political motives, it starts getting manifested in various forms, which in turn usually perceived by the minority as oppression and then they get frightened (secondary fear).

So to restore the delicate balance the primary fear (fear in the minds of the majority) must be mitigated first. But usually, the opposite happens, the govt starts favouring (protecting) the minority, without dealing with the primary cause, which only increases the fear, and then anger, within the majority and the situation gets out of hand. Sometimes it is done intentionally, with both sides, to achieve some political ends.