It has been an extended monsoon this year. Finally, the wind patterns are now reversing. In the capital, they now become dry, come from the west, over Punjab — and Haryana — bringing along the stubble-burning smoke. Autumn is here.

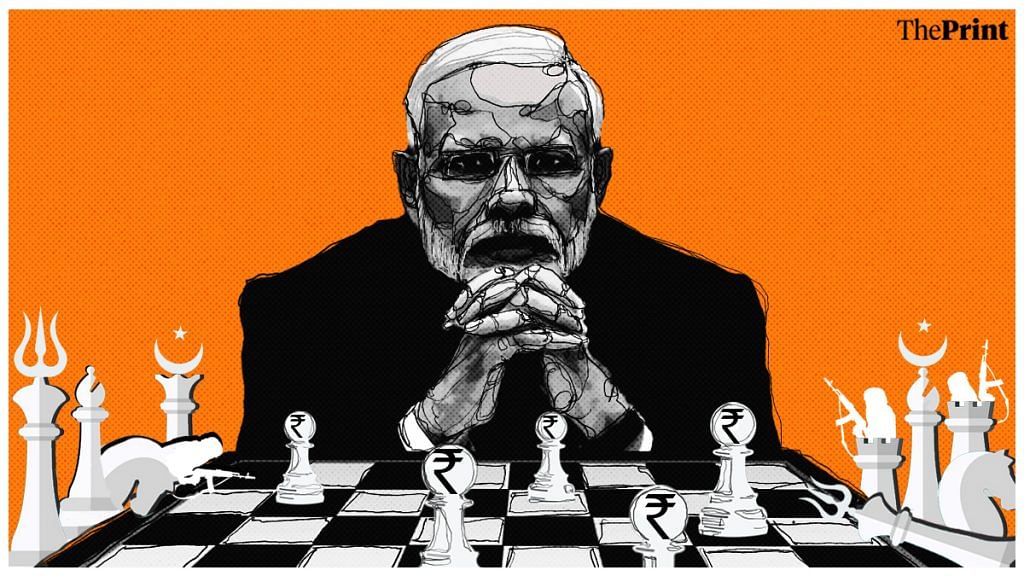

Not quite as clearly as this, but political winds have also shifted. For a couple of years now, as the economy has stalled, the BJP has unleashed the winds of hyper-nationalism with religion (Hinduism) liberally thrown in. This peaked in the months leading up to the general elections, especially with Balakot and Abhinandan.

Then, a voter was convinced India had faced an existential threat from Pakistan for seven decades, nobody had done anything about it, and that Narendra Modi was nailing the problem, with a finality. And that while he would do it mostly by “decisive, deterrent and fearless” military punishment, he was also raising India’s global stature to “isolate” Pakistan. Once enough voters bought into these, they forgot their other, traditional political loyalties and binaries.

The rest then followed. Pakistan is Muslim, it spreads terrorism in the name of jihad, blood-thirsty jihadis are a pestilence for the entire world. Again, the implicit insinuation was that the threat was pan-Islamic, Indian Muslims were not immune, and Hindus needed to consolidate. Of course, all this would not have worked so well but for the spectacularly efficient distribution of almost Rs 12 lakh crore in visible welfare to the poor: Cooking gas, toilets, homes and MUDRA loans. I have written and spoken about these often in the campaign weeks.

In electoral terms, this was a devastating mix: Nationalism, religion, welfare. The opposition’s Rafale talk only invited derision and the issue of the day, even the post-demonetisation growth decline and rising joblessness, was overlooked.

The two assembly elections this week have given our first indication that those winds are shifting. It is definitely not as if Modi has lost any popularity. If he had, the BJP would’ve at least lost Haryana.

It was still his pull that kept sufficient numbers of voters still with the BJP. They’ve depleted substantially from five months ago: By 21.5 percentage points in Haryana, from 58 per cent to 36.5 per cent, for example. But enough still to enable Modi to hail a double-victory on the evening of counting day.

Also read: If anything can defeat Modi, it’s the economy

The early highlights of the India Today-Axis exit poll, the most trusted of all lately, give us some indications. In Haryana, the poll shows that while the BJP still has a healthy overall lead (almost 9 percentage points) over the Congress, in many categories — rural youth, unemployed, farmers, farm labour — it has fallen behind. It must be that in a largely rurban state, the middle class, upper castes and the sizeable Punjabi population have stayed committed and saved it greater embarrassment.

Similarly, in Maharashtra, where the party had run a pretty good government under a clean and well-liked chief minister, it suffered sizeable reverses rather than improvement, as was widely expected. Further, the opposition’s ranks were depleted, with key leaders from both the Congress and the NCP defecting to the BJP, or facing the wrath of the ‘agencies’.

If this relatively indifferent victory came despite these overwhelming advantages, it is important to see who and what broke the party’s blitzkrieg. If it was Sharad Pawar’s NCP rather than the much bigger Congress that stood in the BJP’s way, especially in mostly rural western Maharashtra, it is evident that many farmers and the unemployed have now switched sides.

And remember, all of this happened within 11 weeks of the scrapping of Article 370 in Kashmir, five weeks of ‘Howdy, Modi!’, the talks with Donald Trump and the speech at UNGA. Add to these the TV spectacle of Mamallapuram with Xi Jinping, P. Chidambaram and D.K. Shivakumar’s arrests and key NCP leader Praful Patel’s inquisition for an alleged ‘terror-financing link with Iqbal Mirchi’. Moreover, the hearings on Ayodhya were going on on a day-to-day basis in the Supreme Court, bringing the issue back into national consciousness.

If so many voters shifted in spite of all these factors, within five months of May, it is sufficient indication that the bountiful winds of nationalism, anti-Pakistanism and religious fervour that overwhelmed with emotion the relatively ‘mundane’ concerns of economics and jobs, are now retreating. More voters are now returning to the basics.

Travelling in the general election campaign, we would often run into poor, jobless people who’d complain they were hurting, that the promised boom hadn’t come. Yet they said they will vote only for Modi: ‘Desh ke liye’ (for the nation). That sentiment has not receded. But see it like that voter: I have already overlooked all my personal challenges to vote for Modi to protect my nation. The nation is safe. Now tell me what are you doing for what is really hurting me: Falling incomes, unemployment, and for farmers, mostly static procurement prices.

Also read: Mohan Bhagwat throws a challenge at Modi, revives ‘Swadeshinomics’ amid economic crisis

My central proposition therefore is that the winds of nationalism laden with religion will now yield to those of concern over the stalled economy, unemployment and a general malaise and unhappiness. Fresh noises and action on Pakistan, Kashmir and terror will not be able to reverse these. Except, in the most unlikely event of a larger armed conflict.

Will a favourable Supreme Court decision on the temple make a difference? Maybe some, in the Hindi heartland. But not enough. Too many people are hurting too deep now. They want the return of economic optimism.

We complain often about frequent elections in India. The BJP is in the forefront with the idea of one country, one election. Yet, it is the Modi government that didn’t want elections in Jharkhand simultaneously with Haryana and Maharashtra. Maybe it had sensed trouble? More likely, it understands that it has only one vote-getter, so it is better to give Narendra Modi sufficient time in all three states.

Whether it proves counter-productive now, we will know soon enough as the Jharkhand polls will be announced soon. Will the early winds of change from distant Haryana in the north and Maharashtra in the west reach there, we can only guess. But definitely, the opposition will have its tail out of its legs at last. Cruel thing is, in an all-conquering personality cult, where all victories are credited to one leader, it is tough to immunise him from setbacks. Especially today when it doesn’t even take defeat, but a narrower ‘points’ victory rather than a knockout of the rivals to be seen as disappointing.

The best thing with India’s never-ending cycle of elections is, politics never freezes. Not long after Jharkhand, elections will come to Delhi. The BJP will then need to take a big call: Whether or not to put Modi in front again, risk its becoming Modi versus Kejriwal and go for broke. Will it be worth the risk for a prize that is a small semi-state where the Centre already controls all municipal corporations, land and police? All I can say is, Arvind Kejriwal looks way better prepared than the Congress was in Haryana next door.

Politics in India takes years, sometimes epochs to change. But political seasons do. You can sense that in the dry autumn air now.

Also read: The economy is India’s most potent weapon, but it’s losing its power