The longest general election campaign in our history has just ended as temperatures teased the 50-degree mark in several parts of the country. It is time, then, for some of us to list our key takeaways from it. I am listing 10 here, with brief explanations. A caveat: while politics will inevitably be the running thread, we will talk more about the style and method to pick what stands out.

• The first, without a doubt, is the number of media interviews the prime minister gave. The total comes to three figures, according to some counts from his followers. These included relatively marginal TV channels, daily newspapers and periodicals across regions and publications. For a leader and political group so wary — even contemptuous — of the news media, this is a lot. The important takeaway is that almost no headlines emerged out of these. A possible exception is the interview with Rubika Liyaquat of News18, in which the prime minister said that if he indulged in “Hindu-Muslim” rhetoric in his campaign, he would be unworthy of being in public life. Later, in another interview, he argued that he wasn’t against Muslims and was only exposing the Opposition for appeasement.

The absence of headlines out of so many conversations with a prime minister usually so inaccessible to the media is easy to understand. While caution and the pre-meditated nature of the message to put out is understandable in all campaigns, the questions mostly looked similar, as did the answers. In several, interviewers also complimented the prime minister “for taking all difficult questions”.

• If the first highlight of this campaign is how much the prime minister spoke to the media in one-on-one interviews, the contrast with Rahul Gandhi is equally significant. He did not give even one direct interview to anybody. Neither to a supposedly friendly channel/journalist/YouTube influencer, nor to one seen as hostile, as was the case in 2014 when he spoke with Arnab Goswami. He spoke at short press conferences, sometimes took the odd question on the side, but left direct communication with the media, if at all, to sister Priyanka.

The important political highlight, at least partly owed to this, seems to be that it’s the first campaign where Rahul wasn’t seen to have made a gaffe. In a campaign, where YouTube clips and Instagram reels became such a force, the near absence of any involving him was a standout point. There was the one from his Hyderabad speech where he talked of the Congress manifesto and exposed his flank on the promise of reassessment (including wealth) and redistribution. At least it could be interpreted as that. But that was early, and there was almost nothing besides that. He stuck to his script, and probably to the relief of his minders, did not stray.

• The headlines in his election campaign emerged almost entirely from the prime minister’s campaign speeches. The first thing this tells us is that it was a one-candidate election. Modi was the only candidate for whom the BJP sought votes, and he was the only opponent most of its rivals wanted defeated. It follows that anything he said became news. It could be Katchatheevu, mangalsutra, ghuspethiye, ‘those who produce too many children’, Kartarpur Sahib and Indira Gandhi with the Simla Agreement, or workers from the Hindi heartland facing insults in southern states. If you researched the headlines that set the agenda in this election, phase by phase, probably 18 out of 20 came from the prime minister’s speeches. None from his interviews. Please avoid the trap of over-interpreting this. It isn’t as if the interviews were pre-scripted and the speeches extempore. With Modi, we know that everything is a pre-planned set-piece. That’s why in the speeches, the messages were tailored to a particular audience. Some of them became national talking points.

• Following from this third point is the absence of an overarching national campaign pitch from the BJP. In 2014, it was the disgust over alleged UPA-2 scams and the promise of achche din (better times). There was also an assertion of muscularity in foreign policy, especially towards the Chinese, as the Manmohan Singh government was charged with being weak. The twin proposition, therefore, was massive economic reform and ending corruption on the one hand and a “56-inch chest, laal ankh” approach to national security on the other. In 2019, an unprecedentedly robust national security approach dominated the campaign.

This time, there was no one theme to define the frontrunner’s campaign. On the economy, quality of life, growth or jobs, all smart politicians know it’s perilous to seek votes on performance. Vajpayee and Advani blundered into that in 2004. It’s safer to campaign on promises for the future. That’s the reason for the promise of India becoming the third largest economy in a third Modi government term. If 2014 and 2019 were respectively achche din and national security elections, how should we remember 2024? It was a Modi election. He and the BJP made it all about him. A Modi TINA (there’s no alternative) election. In the process, the party manifesto was forgotten, subsumed by ‘Modi ki Guarantee’. Even when Modi/BJP spoke of a manifesto, it was mostly about the Congress party’s.

• Changed geopolitics hung heavy on this campaign for the BJP. It moderated the discourse on national security. It was brought in here and there, as in the PM saying that while his predecessors only presented dossiers (on terrorists) to Pakistan, his government believed in “ghus ke maarenge” (going deep inside its territory and killing terrorists). This rocket did not have the fuel to last even into the second stage in 2024.

There are two reasons for this. One, that no such notable action had been carried out, or necessitated, in the past five years. And second, the international mess over the Nijjar-Pannun affair made it that much tougher to claim any of that as an achievement. If anything, it dimmed the afterglow of the G20, particularly with US President Joe Biden not coming for Republic Day and the plan of an impromptu Quad summit around that time not working out.

Changed geopolitics also brought in new limitations. Remember, the Chinese came knocking in Ladakh less than a year after the 2019 “national security election”. Their four-year “dharna” in eastern Ladakh, with increased activity across the entire Line of Actual Control, ensured that national security or muscular foreign policy responses weren’t available in this campaign. There was recourse to relatively soft-power options like the evacuation of stranded Indians from Ukraine, with the claim of having got Putin and Zelenskyy to halt the war. It sounds comforting, but lacks the sex appeal of a Balakot or Uri strike.

• If the BJP failed to find a theme except if-not-Modi-then-who, the Opposition also struggled to find cohesion. Targeting Modi as the BJP’s sole candidate was to be expected. But the Opposition was wary of fighting a Modi-versus-who fight. Since Modi was the target and there was so much by way of his speeches and interviews to mine, the Opposition conjured up hundreds of memes and short clips that spread fast. If social media virality on its own could win elections, the Opposition did better than the BJP this time. But it’s obvious that it doesn’t. Beyond this, the parties, especially those in the INDIA bloc, tried breaking this into many local/regional elections. It was easier for the regional parties, but had its limitations in the big, seat-rich states.

• On one issue, the Opposition was quick to its feet and landed an early punch. The initial BJP slogan of “400 paar” was immediately read as a threat to alter the Constitution and take away what’s non-negotiable for many sections of voters: political and individual freedoms for some, religious freedoms for some, and most significantly, for a much larger demographic, the fear of losing reservations. This threw the BJP back and it stopped repeating that boast. Collaterally, for the first time since 1977, it turned the Constitution into an issue of debate. Indian voters showed by and large that they value their Constitution and don’t want anybody taking away what is central to it.

• While the Constitution became an icon and pushed the BJP back on the 400-seat claim, the Opposition didn’t succeed in making institutional capture and damage to individual liberties into an abiding theme. They did keep invoking the Emergency, and ran into three challenges. One, that a majority of voters today were born after 1977 and have no memory of the Emergency. Second, the Emergency was promulgated by the Congress and the most familiar member of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty today. And third, the Emergency was a mass atrocity shared among crores, especially in the Hindi states. Today, the ongoing denial of freedoms, especially the use of the agencies, is limited to some select elites, from opposition leaders to civil society and the media. It was very tough to turn into an issue of mass anger.

• While the campaign was almost entirely about Modi, the BJP saw the rise of another key campaigner in Amit Shah. He addressed 188 rallies across the country (according to The Times of India), was a good magnet for the faithful and prolifically made headlines. We had noted his rise as a dominant BJP figure in a 2017 article headlined ‘Rise of the party commissar’. While that remains, this election marked his stepping beyond that backroom. The use of the expression ‘stepping beyond’ rather than ‘stepping out’ is deliberate. It signifies that he hasn’t left the backroom, where he is such an important and powerful figure for the BJP. He’s been the second most powerful figure in the BJP since 2013. Now, he’s also the second most visible.

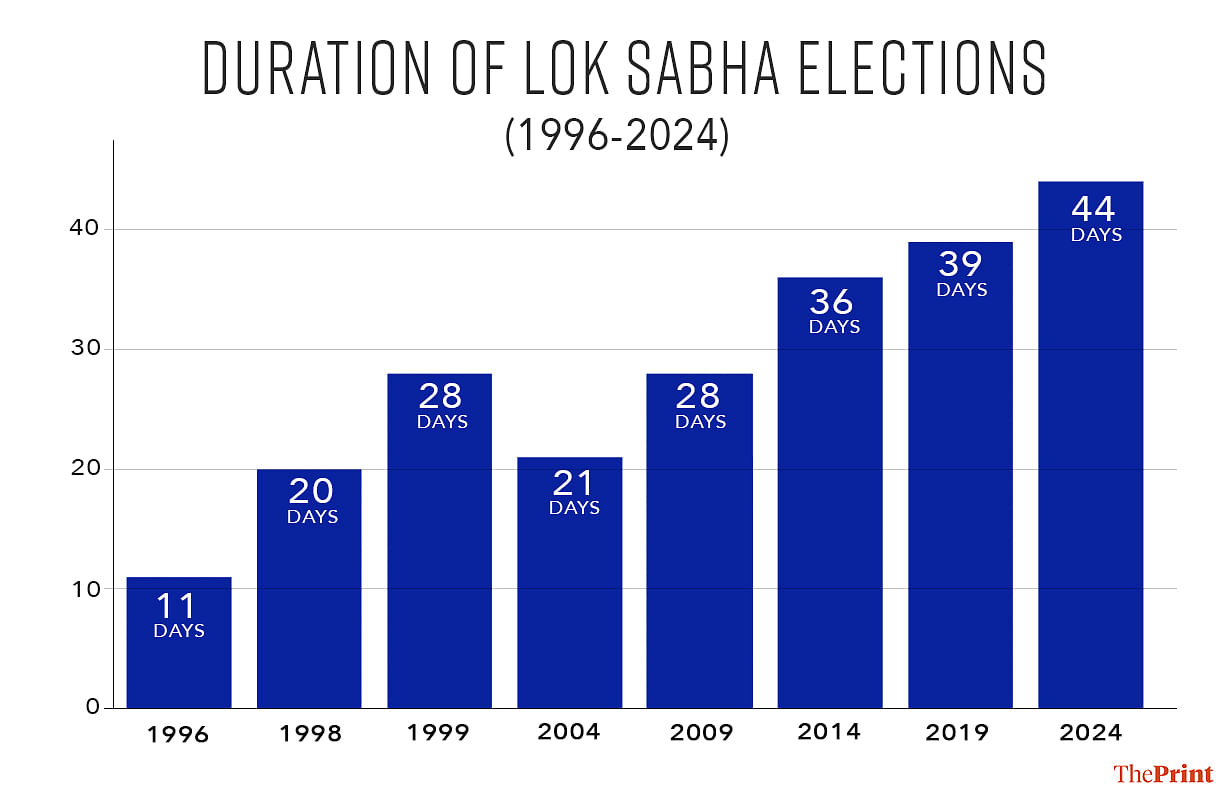

• And finally, a rant. Did this election really have to go on for 44 days? Check out this graphic and this data. The 1996 election lasted all of 11 days. The next, 1998, took 20, and 1999 stretched over 28 days. It moderated a bit to 21 in 2004 but has been rising since then, going up to 28 again in 2009, 36 in 2014, 39 in 2019 and now 44 days.

It’s a painful paradox. On the one hand, connectivity and communication have improved dramatically, the paramilitary forces have greatly expanded and we rightly boast to the world about our super-efficient electoral process — with EVMs, the end of booth-capturing, and repolls rarely being ordered. On the other hand, our campaign season is getting longer.

I know it will be said that the Election Commission did this to enable Modi to reach more parts of the country as his party’s sole messenger. As our numbers show, however, the campaign season has been lengthening even as our infrastructure has been improving. It beats me why the EC as an institution should want to continue doing this. Unless the idea is to catch up with a full IPL season, 61 days. We shall see in 2029.

Also Read: Abki baar 90 paar for Congress? Why even 30 more seats will ruffle BJP

Why not start the third term with a glittering press conference in Vigyan Bhavan, or Bharat Mandapam. Giving the fourth estate the respect and salience due to it in a democracy.

Modi is the only one to survive so much hatred from Lutyen media and Khan Market Gang.